The Battle of the Somme: contemporary sources – Part 1

On the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme we take a look at the contemporary sources that are available in the Information and Reference Library. In part one we look at The Times and The Times History of the War.

In the days before the internet, radio and TV the main sources of information for people were newspapers and magazines, and news reel that were shown at local cinemas. During the conflict these news sources were censored, in part so as not to damage the moral of the public, but also to ensure that no military or operational information was revealed to the enemy. So, they do not not provide an objective account of the War but they do provide us with the information that was available to the general public. Another important source of information was the letters sent home by those who were fighting. These were censored too, though often very crudely with words and phrases being struck through with a pen, so that they were often still discernible.

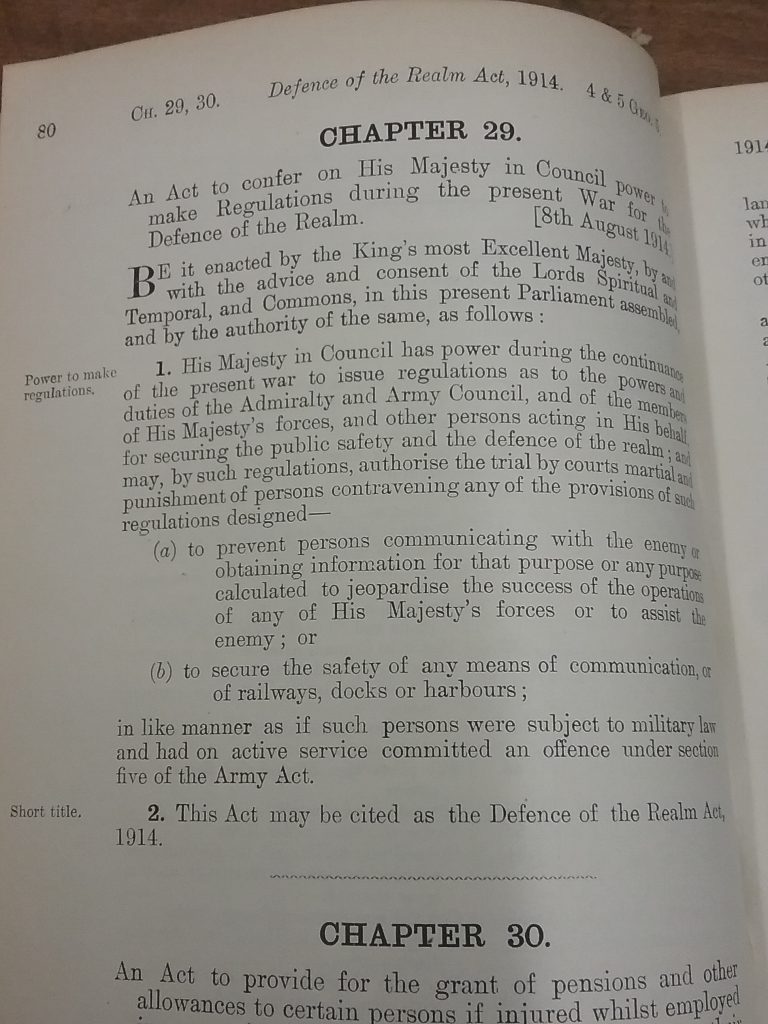

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), which came into effect shortly after war was declared in August 1914 and it gave the authorities power to restrain criticism of the war effort. One of its regulations stated: “No person shall by word of mouth or in writing spread reports likely to cause disaffection or alarm among any of His Majesty’s forces or among the civilian population.”

Many newspaper proprietors were pro-war with their newspapers reflecting this and journalists themselves would self-censor their work as they didn’t wish to hinder the war effort or appear unpatriotic.

However, censorship of newspapers wasn’t so strict that no criticism of the government was allowed. Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of The Times and the Daily Mail, waged a campaign in his newspapers against the Secretary of State for War and national hero, Lord Kitchener. It was the Times’s war correspondent, Charles à Court Repington, who broke the story in May 1915 of the shortage of artillery ammunition. This became known as “the shells crisis” and it had suitably explosive political results. The Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was forced to form a coalition government with David Lloyd George becoming Minister of Munitions – it was a precursor to Lloyd George replacing Asquith.

The obverse to censorship was the anti-German propaganda, known as “atrocity propaganda”, which was used to justify the War and to stir up anti-German feelings.

At the outbreak of the war Kitchener banned reporters from the front. However, two determined correspondents, the Daily Chronicle’s Philip Gibbs and the Daily Mail’s Basil Clarke defied the ban and acted as “journalistic outlaws” to report from the front line. Gibbs was arrested, warned that if he was caught again he would be shot, and sent back to England. Clarke, after reporting on the devastation in Ypres following the German bombardment, returned home after a similar warning. In 1915 the High Command began to realise that having the press on their side could be a major advantage and introduced a system of accrediting war correspondents.

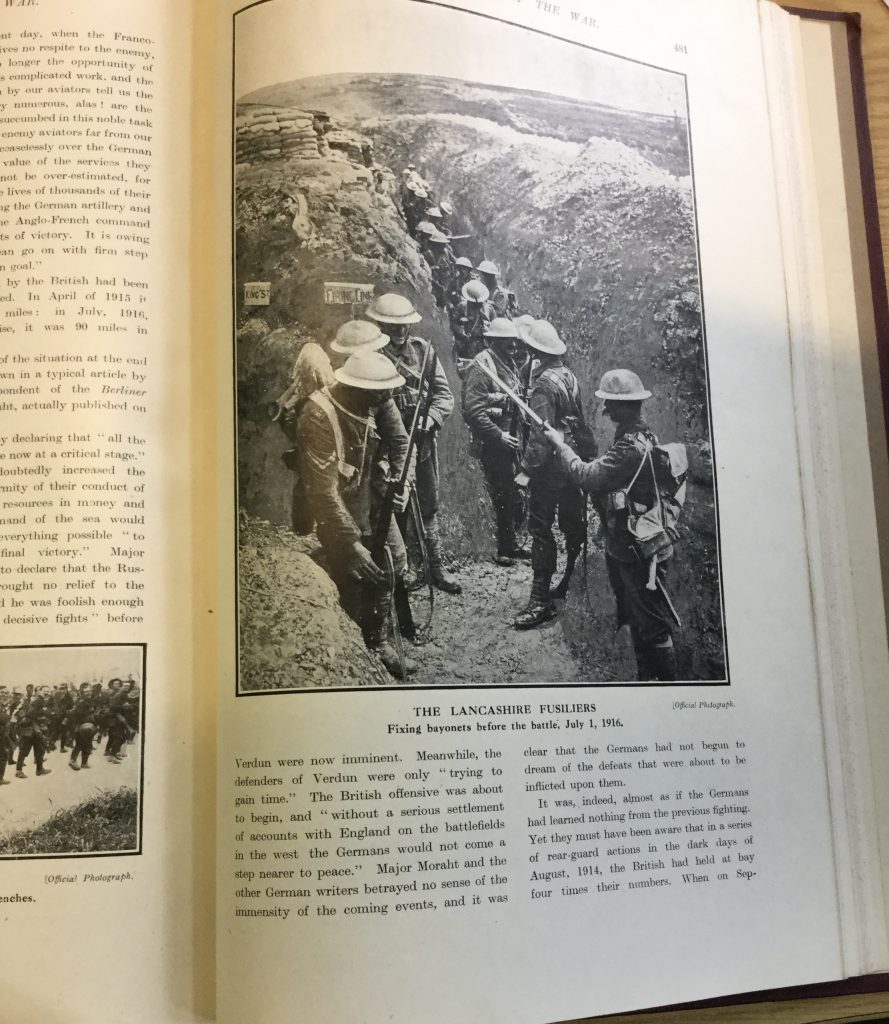

In March 1916 the first official war photographer was appointed and sent to the Western Front. He was Ernest Brooks and he was followed by a dozen other war photographers who were all given the army rank of lieutenant and were subject to military discipline. Interestingly, censorship of their work affected only what photos could be published, not taken, and thereby left these photographers generally free to choose their subject matter.

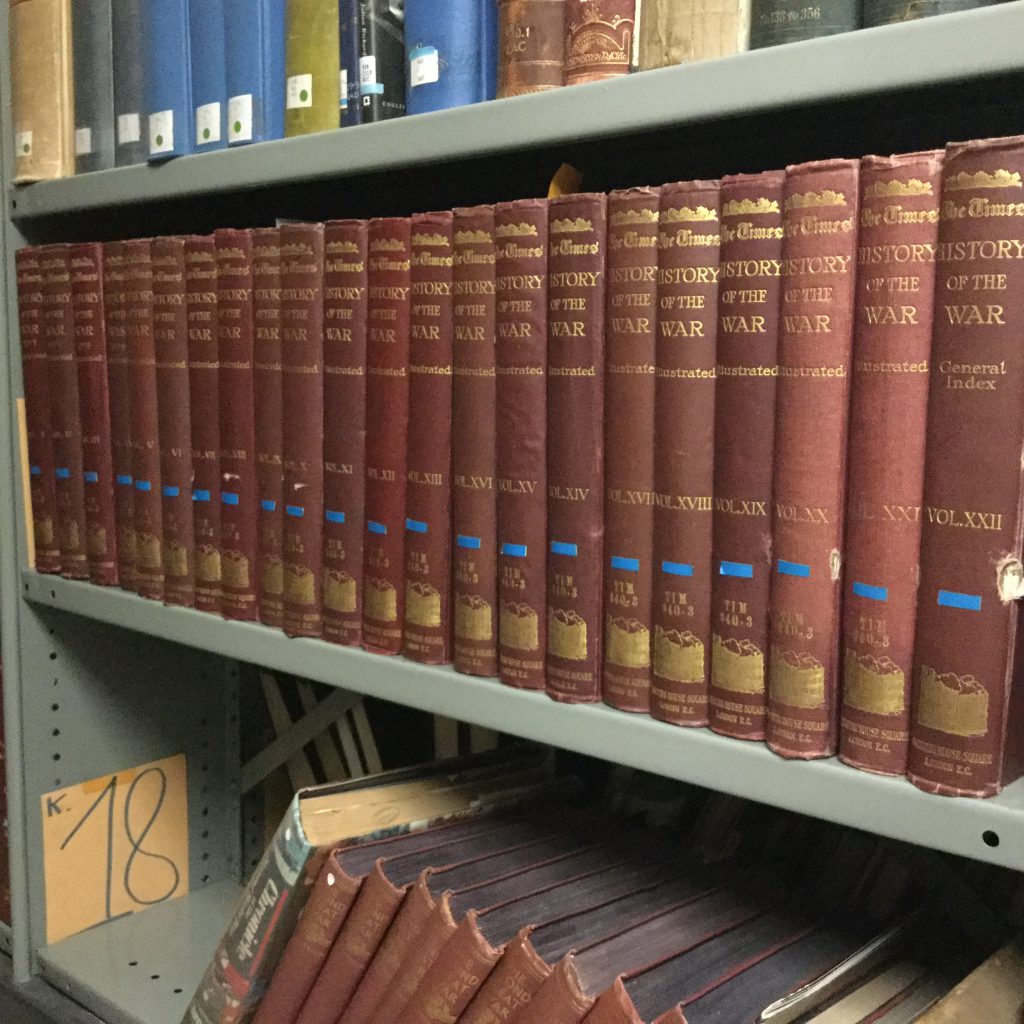

The Times History of the War

When war was declared in August 1914 Wickham Steed, the editor-in-chief of The Times, decided that the paper should embark on an extraordinary project to produce a separate weekly supplement, in addition to the authoritative daily war reports in the paper itself. This supplement consisted of 40 pages of in-depth analysis. The result was The Times History of the War, which was published as a 22 volume set in 1921. It consisted of 11,000 pages – 6 million words with thousands of photographs, graphics, illustrations and maps.

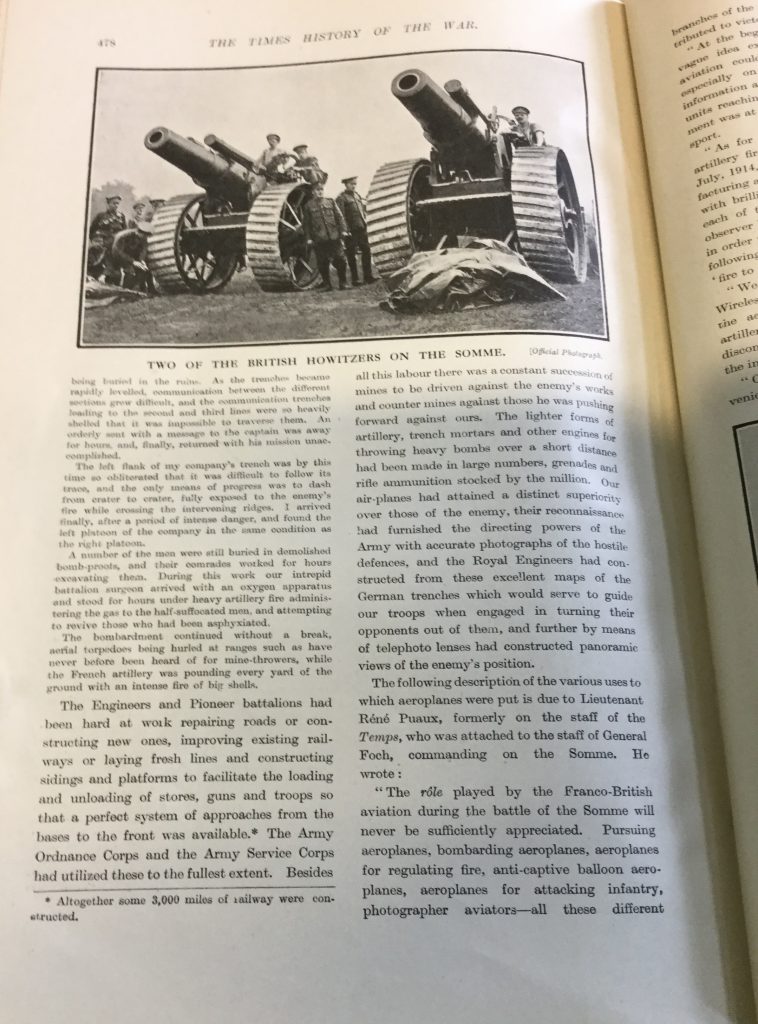

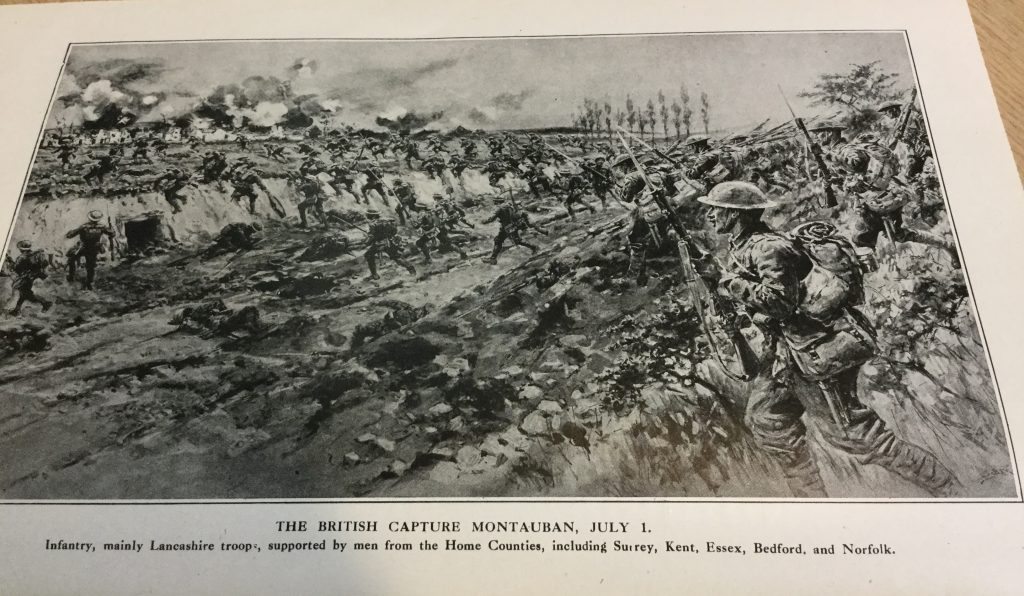

The supplement published on the Battle of the Somme, in volume 9, has photographs from the official photographers

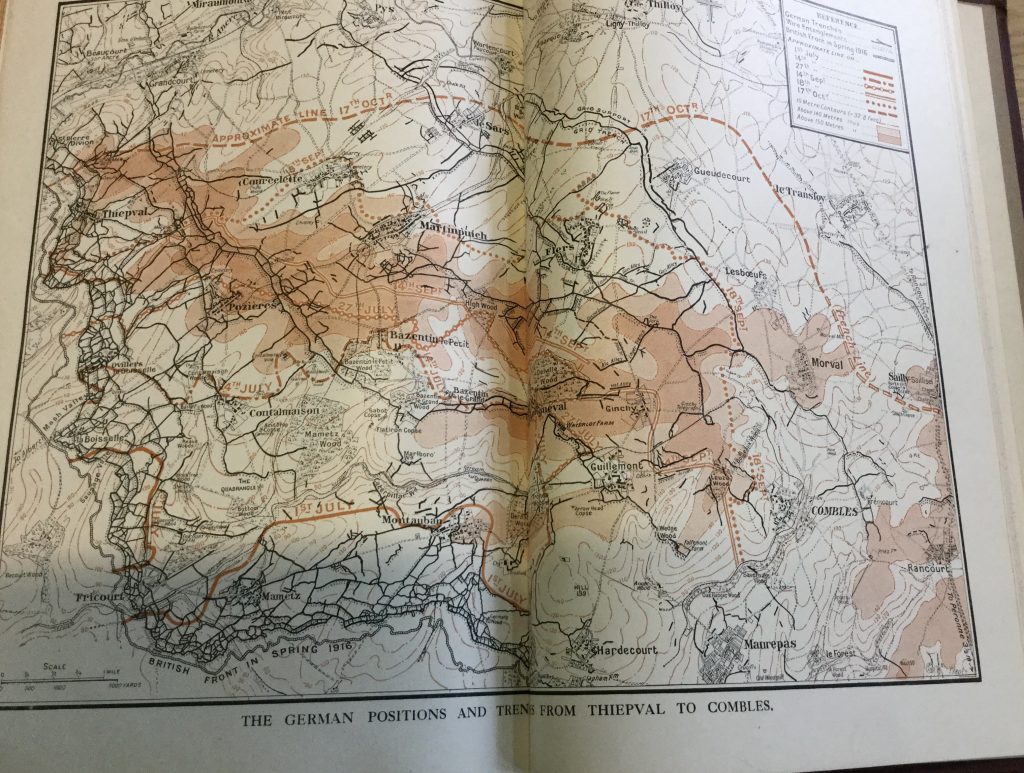

and includes a detailed map showing the positions of the trenches along with

drawings, either based on photographs or sketches that had been made at the front by wartime illustrators or official photographers. One such artist was Fortunino Matania who was employed by the Ministry of Propaganda to depict life on the Western Front.

The accompanying text gives a very detailed account of the battle.

This series is a reminder of how many different theatres of war comprised this first truly global conflict.

The Times

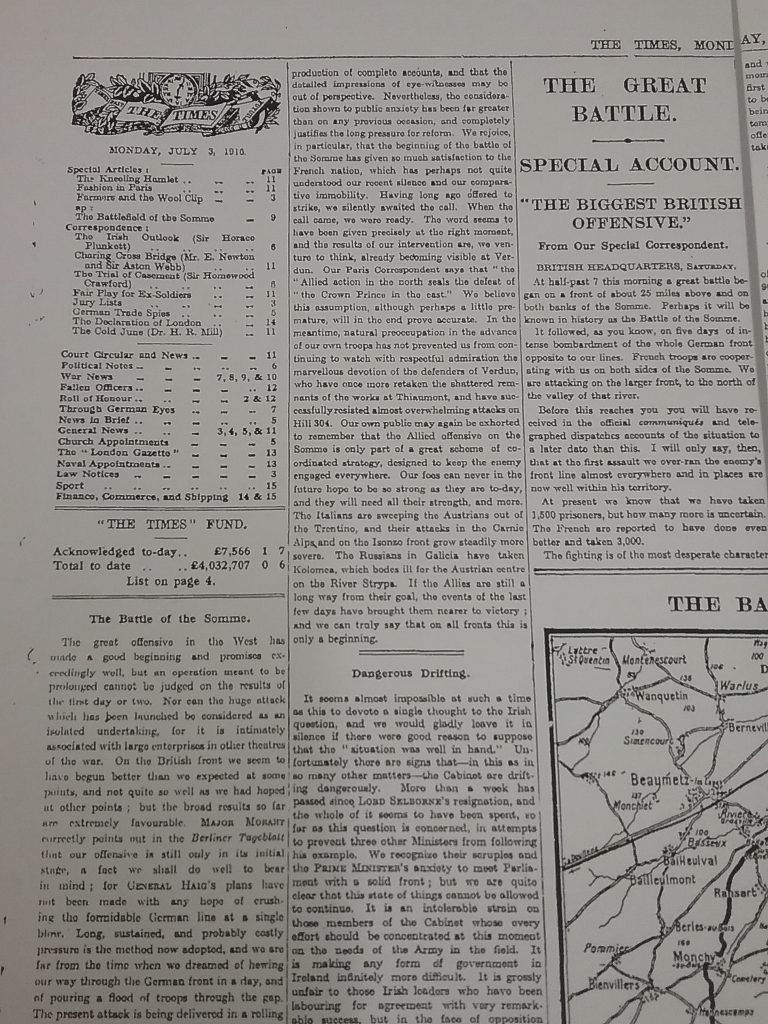

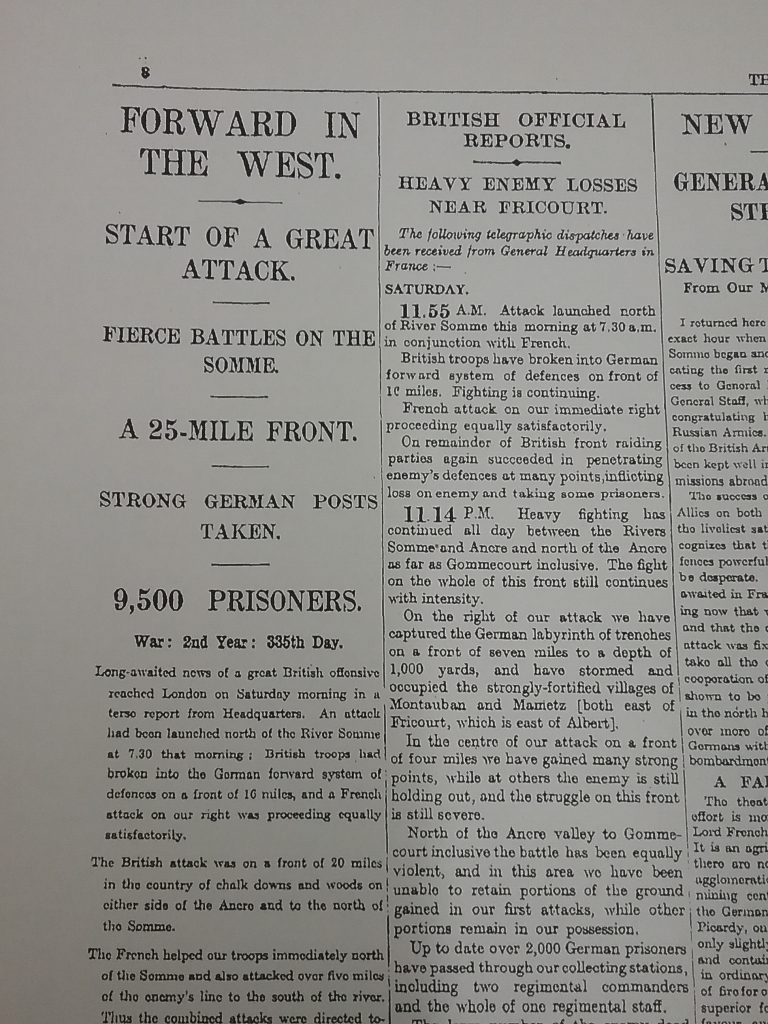

The Battle of the Somme began on Saturday July 1 and detailed reports from the paper’s special correspondents appeared in the Monday July 3 edition of the paper. There were also detailed maps of the battlefield.

Sources

The Public and General Acts Passed in the Fourth and Fifth Years of the Reign of His Majesty King George the Fifth.

The 22 volumes of The Times History of The War are held in the reserve store and can be viewed at the Information and Reference Library. The Times is taken in hard copy and kept for 6 months. Library members can access earlier back issues via Newsbank and The Times Digital Archive.

Other contemporary materials are available from:

Library members can access the entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Oxford Art Online for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text.

Related articles

[ Fiona Campbell, Library A