London: the city as a phoenix [Part 2] – the Blitz and St. Paul’s

The Great Fire of London, which destroyed and devastated four-fifths of the city, began on 5th September 1666. 274 years and 2 days later, on 7th September 1940, the city of London again faced destruction when the Blitz began (short for Blitzkreig, German for lightning). The Blitz was to prove just as devastating as the Great Fire, not just for the city but for the West and East Ends, the London suburbs and for many major cities such as Liverpool, Portsmouth, Hull and Bristol.

One of the casualties of the Great Fire was St. Paul’s Cathedral (see London: the city as a phoenix [1]) but, unlike the city around it, the cathedral was fairly unscathed.

The night of 29 December 1940 saw a particularly heavy raid and Sir Winston Churchill, realising that the cathedral’s destruction would be a serious blow to British morale, directed all local fire-fighting resources to give special attention to saving St Paul’s. As many as 29 incendiary bombs fell on, or close to, the cathedral, but they were put out by volunteer firefighters. One incendiary bomb hit the roof and, though it lodged in its timbers, it simply burned through and fell to the floor where it was smothered.

Herbert Mason, the Daily Mail’s chief photographer, was on fire patrol that night on the roof of the newspaper’s building in Carmelite Street to the south west of St. Paul’s. He took the now iconic photograph of the dome of St. Paul’s, appearing illuminated out of the dark, surrounded by swirls of smoke with the silhouettes of bombed buildings in the forground. He said of taking the photograph that:

‘I focused at intervals as the great dome loomed up through the smoke. The glare of many fires and sweeping clouds of smoke kept hiding the shape. Then a wind sprang up. Suddenly, the shining cross, dome and towers stood out like a symbol in the inferno. The scene was unbelievable. In that moment or two, I released my shutter.’

This photograph has come to symbolise the resilience of London and Londoners.

In the aftermath of the night of 29 December, there was some debate among government censors over whether Mason’s photograph should be published. It wasn’t until 31 December that it finally appeared in the Daily Mail below a headline which read War’s Greatest Picture: St Paul’s Stands Unharmed in the Midst of the Burning City . It was cropped to reduce the number and prominence of the damaged buildings in the foreground.

However, the German press interpreted the photograph differently and when the photograph appeared on the cover of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, later on in January, the headline was The City of London Burns!

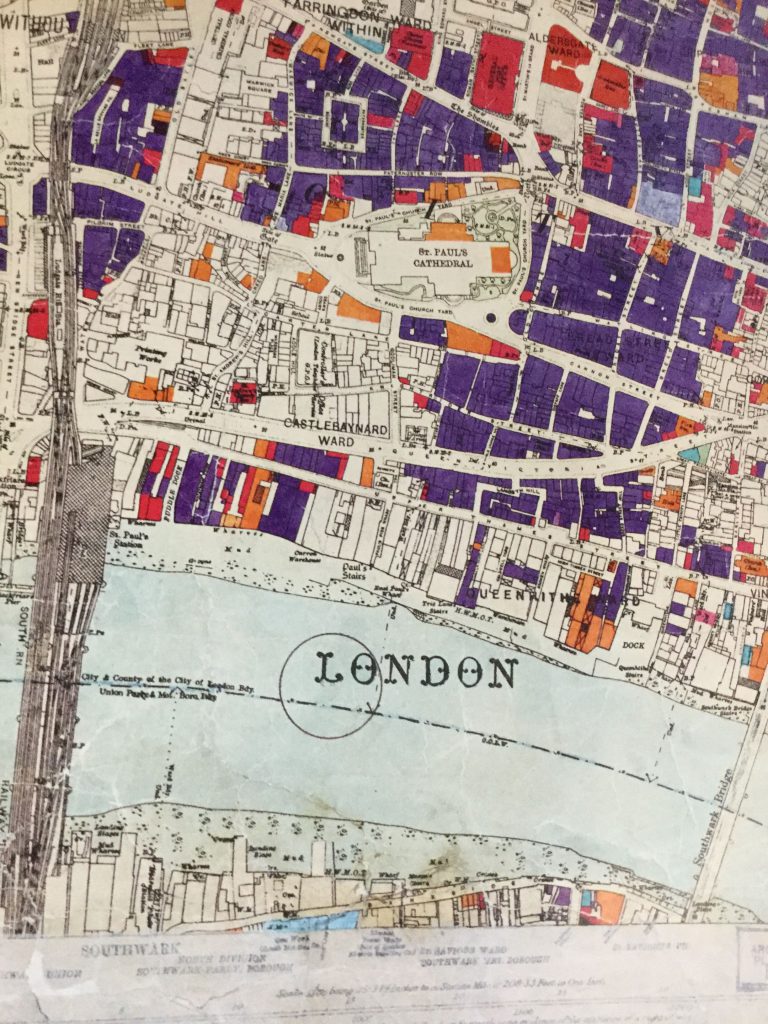

There was a popular myth that St. Paul’s wasn’t damaged at all during the Blitz but, as the London County Council Bomb Damage map clearly shows, two parts of the building are marked as “general blast damage – not structural ” (coloured orange) while buildings in the vicinity are “damaged beyond repair” (coloured purple). A V-1 landed just south of St. Paul’s in the River Thames, shown by a large circle.

The bomb maps were complied by the London County Council, as a record of destruction and damage and to help with planning and rebuilding. The most serious category was “total destruction” denoted by black on the map. These detailed maps show the extent of the damage London suffered as a result of enemy destruction, especially within the city of London.

In the early morning of 16/17th April 1941 there was a direct hit that damaged the north transept floor of St. Paul’s, but this was the most serious damage that occurred.

The bombing continued for 57 nights consecutive nights, with some bombing happening during the day and there were regular air raids until 11 May 1941 by which time 1800 tonnes of high explosives had been dropped on the capital city.

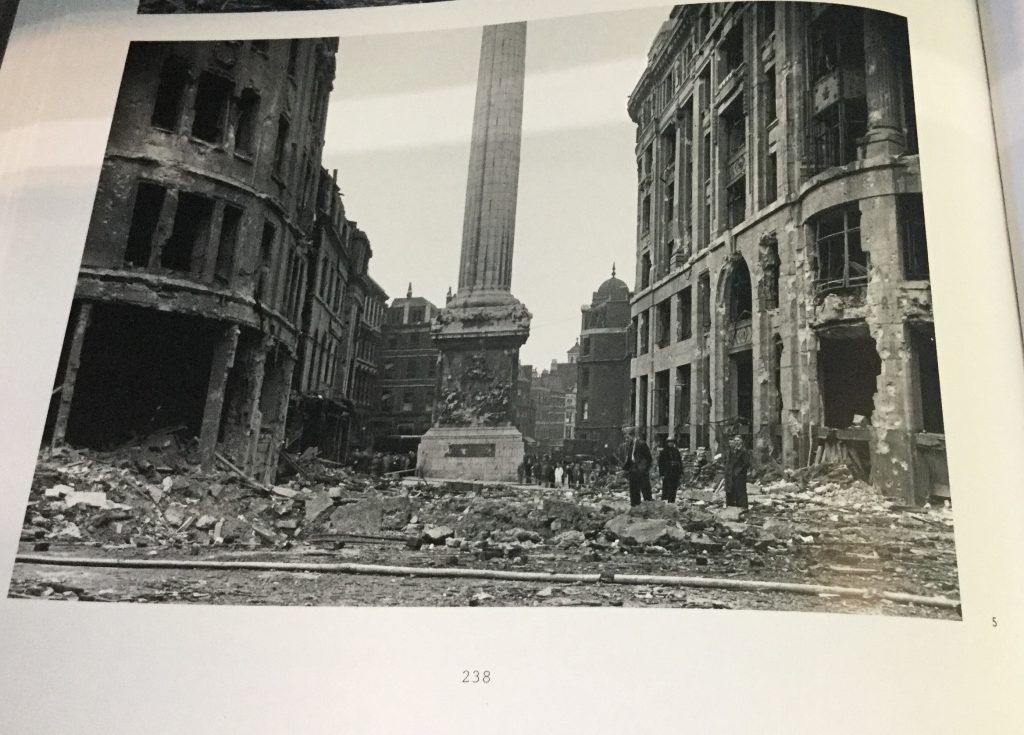

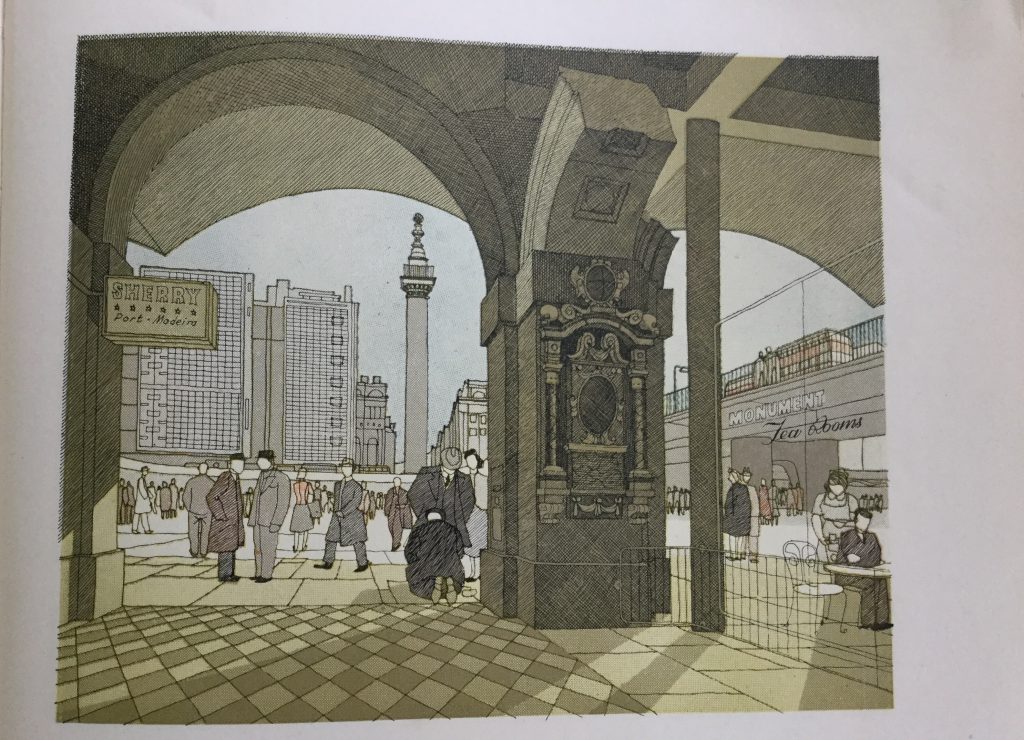

Another structure that was unscathed was the The Monument, built to commemorate the Fire of London, and the photograph above shows it surrounded by the bomb damaged King William Street. This was photographed by either Arthur Cross or Fred Tibbs. They were both City of London police constables, who were keen amateur photographers and they made a complete official photographic record of the bomb damage in the city for the Corporation. (See under further sources for details for how their work can be viewed.)

St Paul’s may have had little damage but other buildings in the city were not so fortunate: the Guildhall was severely damaged, eight churches designed by Sir Christopher Wren were destroyed and many railway stations and hospitals were hit. More than 160 people were killed, including 16 firemen.

Rebuilding the City

Even as the war was still being fought architects, planners and reformers saw the destruction of London as an opportunity for reconstruction, planning and redevelopment. London would no longer be blighted by what they saw as unplanned and ugly suburban sprawl, traffic congestion, overcrowded public transport, urban chaos and insufficient green spaces. How the area around St. Paul’s, which had become an even a greater icon of London during the war, was going to be dealt with was always going to be contentious.

In October 1942 the Royal Academy of Arts Planning Committee, under Sir Edwin Lutyens, (architects had been Academicians since its foundation) published London Replanned. The proposals for St. Paul’s involved duplicating the deanery and chapter house for the sake of architectural symmetry, without any concern about cost or usage.

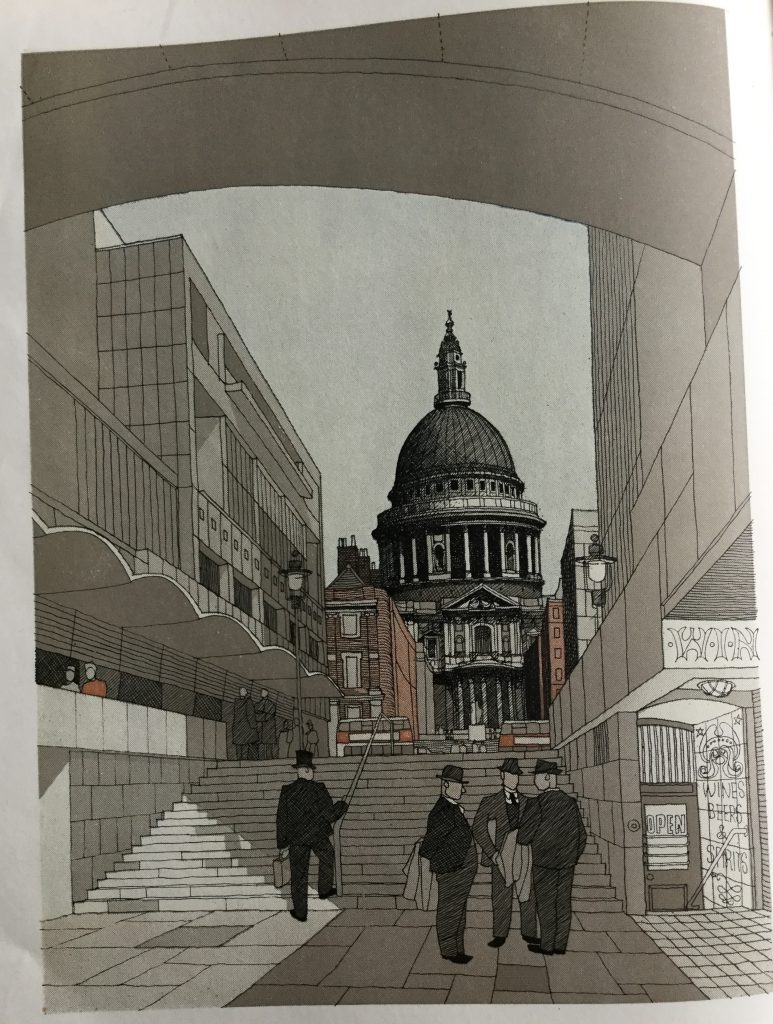

In July 1944 the City’s Improvements and Town Planning Committee put forward preliminary proposals for post-war reconstruction. They saw this as an opportunity to modernise the city by widening streets and opening up vistas, improving traffic flow and pedestrian access. For St. Paul’s it was envisaged that they would be open space to the east, west and south of the cathedral with an improved vista provided by the widening of Ludgate and steps leading down to the Thames. The proposals included significant office space to generate revenue for the city. They were unpopular with most outside the city, being seen as overly commercial and unimaginative and the plans to increase the amount of office space went against Abercrombie’s County of London Plan of which had been published in 1943.

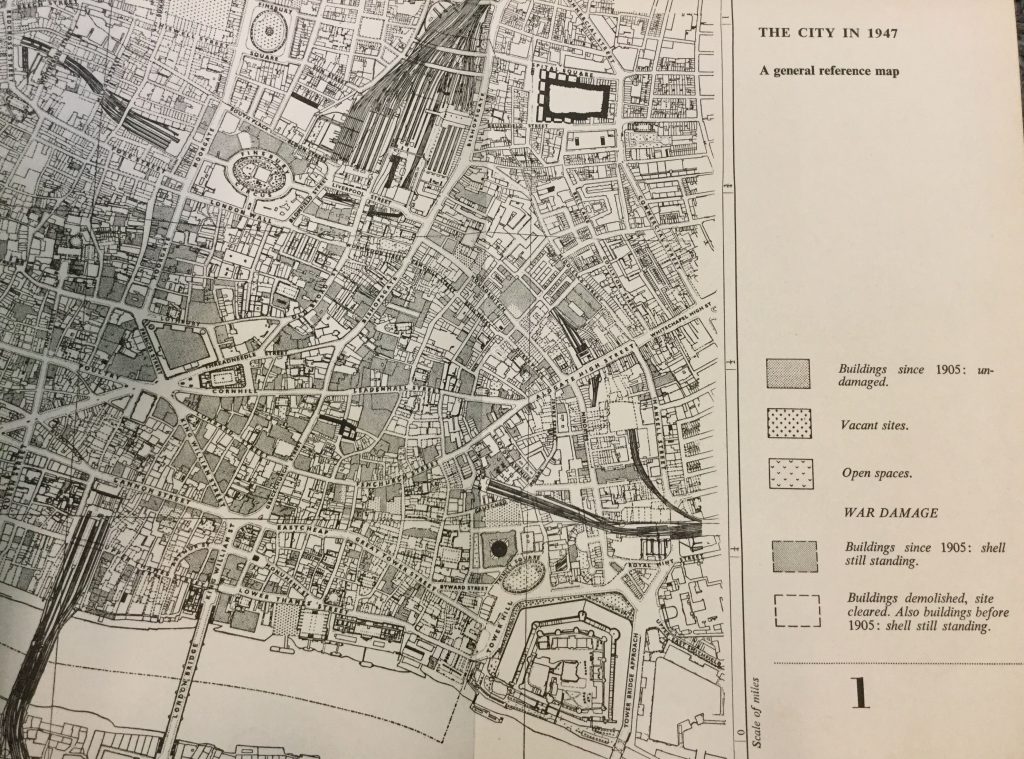

The new Ministry of Town and County Planning forced the Corporation come up with another plan and in April 1947 Dr C H Holden ( architect of many Modernist undergrounds stations) and Professor W G Holford presented their final report to the Improvements and Town Planning Committee of the Corporation.

It was published as a book in 1950, entitled The City of London: a record of destruction and survival. It provided a detailed analysis of of the current state of the city and the damage it had suffered, a history of the development of the city, and presented a bold vision for modernising the city by improving traffic flow, creating precincts around St. Paul’s and The Guildhall, and improving pedestrian access. The plans were incorporated into the County of London Development Plan of 1953.

The report recommended expanding the open space to the south and east of St. Paul’s, where many buildings had been destroyed and damaged during the war, and keeping the vistas of the cathedral, with the new churchyard buildings having a low roofline and dressed with brick and stone. The debate continued amongst architects, the Church Commissioners and the Corporation, with no decisions being taken, and in 1955 the Minister for Housing and Local Government required the Corporation to appoint a consultant (this was Holroyd again) to draw up comprehensive plans for the area and these went before a public inquiry in 1957. Permission was finally granted to rebuild north of St. Paul’s in 1958 and building work was finally finished in 1967.

Even today there is still great concern about building developments in the city and the effect they have on London’s skyline and the iconic view of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Related links and source material

Amateur Photographer

Article about Herbert Mason’s photograph of St. Paul’s.

The Cross and Tibbs Collection

The collection is part of the Collage: The London Picture Archive. This database has 1/4 million images from the London Metropolitan Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery.

London Can Take It

Ministry of Information, GPO film Unit film about the Blitz.

Map of London V2 rocket sites

Bibliography

Bomb Damage Maps

The City of London: a Record of Destruction and Survival

County of London Plan

Greater London Plan 1944

The Making of Modern London

St. Paul’s : The Cathedral Church of London 604-2004

Images sources

- Page 95, Bomb Damage Maps

- Page 99, St. Paul’s : The Cathedral Church of London 604-2004

- Page 238, Bomb Damage Maps

- Page 24, The City of London: a Record of Destruction and Survival

- Page 254 The City of London: a Record of Destruction and Survival

- Page 235, The City of London: a Record of Destruction and Survival

Library members can access the entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text.

If you use Pinterest then why not have a look at the Richmond upon Thames Libraries Pinterest board entitled London: the city as a phoenix?

[Fiona Campbell, Library Assistant]