The Royal Air Force -100 years in the air

1 April 2018 represents the 100th anniversary of the creation of the Royal Air Force, the world’s oldest independent air force. The RAF, and its associated female branch the WRAF, were formed from the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) on 1 April 1918 and the RAF took its place beside the British Navy and Army as a separate military service with its own ministry.

It was only 15 years previously, in 1903, that the Wright Flyer had made the first successful heavier-than-air manned, controlled, sustained flight; the culmination of decades of aviation experimentation. A handful of years later, in 1908, Samuel Cody made the first British military aircraft flight at Farnborough.

By 1911 the British Army had developed the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers (No. 1 Airship company at Farnborough and No. 2 Aeroplane Company at Larkhill) while the Royal Navy had created a flying school at Eastchurch.

In April 1912 a Royal Warrant was given to establish The Royal Flying Corps made up of a Military Wing, a Naval Wing, a Central Flying School (to train pilots for Navy and Army) and the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough (to research aviation). The first commander was a Captain of the King’s Hussars, (promoted to temporary Major) Frederick Sykes. At this stage the RFC had only four working aircraft!

Early on Sykes was determined that the Royal Flying Corps should have a motto and a young officer of the Royal Engineers, J.S. Yule, who had read Rider Haggard’s book The People of the Mist, suggested the motto he had seen quoted there: ‘Per ardua ad astra’ which translates roughly as ‘Through adversity to the stars’. Deeming this an appropriate message for his fledgling corps, Sykes put this forward and later that year it was officially granted Royal Assent. Per ardua ad astra remains the motto of the Royal Air Force to this day.

The Royal Flying Corps grew very slowly between 1912 and 1914 and even at this early stage the Admiralty was not in favour of having a combined aviation service. In 1913 the Admiralty established 6 air stations along the east coast of England and Scotland pursuing their vision of using aircraft to protect the coast. In June 1914 the Naval Wing was removed from the RFC, forming the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in July 1914.

At the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914 the Royal Flying Corps consisted of four squadrons with a complement of 105 officers, 755 men, 95 transport vehicles and 63 fighting planes mainly BE2s, Bleriot monoplanes, Farman biplanes, Avro 504s and BE8s taking on the roles of reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and aerial photography. Bombing and rudimentary fighting roles came later – often with hand held guns.

There was a great deal of early scepticism about the potential contribution of aircraft in warfare and General Haig’s opinion was not an isolated view when he said in 1914: “I hope none of you gentlemen is so foolish as to think that aeroplanes will be usefully employed for reconnaissance purposes in war. There is only one way for commanders to get information by reconnaissance, and that is by the cavalry.”

It soon became apparent that the Union Flag markings that were painted on British planes were a liability as, from a distance, the red St George’s Cross could be mistaken for the black German ‘Iron Cross’. The French were using a roundel in red, white and blue and in December this was adopted for British planes by reversing the colours of the concentric rings. The flag was retained in miniature on the wings and tail.

The usefulness of airplanes in fighting was hindered by the difficulty of correctly aiming machine guns that were fitted to the sides, back or wings of aircraft. Nose guns could only be fitted to rear-engine types. In July 1915 the German Fokker Monoplane entered the scene, a single seat fighter equipped with a machine gun that worked with an interrupter gear to fire through the arc of the propeller. With this purpose-built and deadly machine the Germans began to change the way air warfare was carried out, having squadrons for fighting, bombing and reconnaissance – each with specifically equipped aircraft.

By the time of the battle of the Somme in July 1916, the RFC had 31 squadrons with 210 serviceable machines and 246 men to fly them. The intensity of the fighting meant that both men and machines were in constant demand with each squadron averaging 10 losses of aircraft per month and a correspondingly high casualty rate.

The RFC continued to expand as did the manufacture of aircraft and by 1916 there were 1,782 machines delivered compared to just 84 in 1914. By 1918 the RFC consisted of 200 squadrons and more than 7,000 aircraft were delivered between January and the end of the war.

Alongside the pressure to increase the force of pilots and numbers of machines was a corresponding requirement for ground personnel including mechanics. In order to release men for fighting, both the Navy and the Army recruited women to work as cooks, clerks, wireless telegraphists, code experts, chauffeurs, instructors and electricians. The Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS – the ‘Wrens’) and the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) were formed between 1916 and 1917.

The contribution of aircraft in the war was being demonstrated on several fronts:

In France aerial support for the army became of increasing importance. While airplanes were not generally being used offensively they very quickly became vital for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. The Germans, flying specialised Schlachtstaffeln (ground attack) aircraft were able to target specific points on the battlefield and the British planes would engage them in order to divert them from their targets. As British aircraft at this stage were neither as agile nor as well armed, losses were very high. The Battle of Arras in April 1917 was a particular low point. Known as Bloody April this month alone cost the RFC 300 aircraft.

In addition to their increasing role in battle, aircraft were also vital in defending the home front against air raids. Between November 1916 and May 1918 the Germans launched 51 airship raids and 52 aircraft raids on Britain causing considerable damage including 1,414 fatalities and 3,416 other casualties. Many of the strategies developed at this time were later implemented during World War II.

Meanwhile at sea the Navy was pioneering the use of aircraft in reconnaissance and submarine spotting and in July 1918 a modified Royal Navy ship the HMS Furious was the first to launch airplanes in a carrier-borne attack when seven Sopwith Camel biplanes were launched against a German airship base at Tondern. Unfortunately, since it was impossible to land these planes on the deck after their successful operation, the pilots had to ditch next to the Furious on their return but the concept had been tested and proven successful.

From the middle of 1917 the British government, aware of the increasing importance of aircraft both at home and abroad, decided that reorganisation was essential. Spurred on by concerns that Germany was far ahead of Britain in terms of using aircraft in war, General Smuts compiled a report that recommended the creation of a unified Air Force and the promotion of the existing Air Board to Ministry status.

There was a great deal of disagreement and concern over this proposal including the timing of the changes in the middle of a war and the loss of independent control by the Navy and the RFC.  Despite opposition, the government went ahead and on 29 November 1917 the Air Force Act received Royal Assent and on 1 April 1918 the Royal Air Force came into being.

Despite opposition, the government went ahead and on 29 November 1917 the Air Force Act received Royal Assent and on 1 April 1918 the Royal Air Force came into being.

Major General Hugh Trenchard was made RAF Chief of the Air Staff but resigned before the actual launch of the RAF. Major General Frederick Sykes (who had commanded the fledgling RFC before the war) was promoted to Royal Air Force Chief of the Air Staff and went on to fulfil this role until April 1919 guiding the new service through the final months of the war and through a period of great change and upheaval.

On its creation the RAF was an amalgamation of approximately 250,000 personnel and 23,000 aircraft formerly of the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps. For the moment the Royal Navy maintained control of its carriers HMS Furious, Argus, Ark Royal and Pegasus – manned with pilots from the RAF.

The women’s branch, the WRAF was established alongside the RAF and women who were currently working as clerks, fitters, drivers, cooks and storekeepers on RFC and RNAS bases as well as women who had volunteered or were enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers and other women’s services were offered the chance to join. After WWI the women’s services were disbanded and had to be revived at the outbreak of WWII.

In June 1919 King George V created four medals specifically to be awarded for services in the air. Two for commissioned ranks; the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy in the air, and the Air Force Cross (AFC) for gallantry while flying but not on active operations against the enemy. As well as two for non-commissioned personnel; the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) for exceptional valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying in active operations against the enemy, and the Air Force Medal (AFM) for courage or devotion to duty in the air. In 1993 the DFM and the AFM were discontinued and the DFC and AFC were extended to personnel of all ranks.

The RAF was scaled down after the end of the Great War although it continued active operations overseas in Iraq, India, Palestine and elsewhere in the Empire. Throughout the 20s its existence came under attack repeatedly from the Navy and the Army arguing that their particular needs would be better served by returning control of air services to them. This argument was apparently settled in 1921 by an independent report to the Committee of Imperial Defence and there was even a plan to expand the Air Force although this did not materialise. Further attempts by the Army and the Navy to control aviation and create separate branches were raised in 1922 and 1923. In 1924 the sub-committee examining the Navy’s claim concluded (with concessions) that the all flying units of the Navy were to be a part of the Fleet Air Arm of the RAF. The Navy, resenting this decision, continued to raise this issue repeatedly.

The atmosphere in the post war period was one of financial restraint and pacifism and there was little public or governmental interest in maintaining let alone updating and expanding military forces. However despite repeated attacks, the independence of the RAF was preserved and a number of the structures and institutions of the RAF were put in place. From 1929 the first steps were taken towards developing the aircraft that would become vital in the coming war; including the quintessential trainer, the de Havilland Tiger Moth (in service from 1932 until 1959) and the development of the RAF’s 1931 Schneider Trophy winning Supermarine S6B – a precursor of the Supermarine Spitfire.

From 1933 onwards there were signs that Germany was becoming increasingly militant while Britain was still pursuing a policy of disarmament. In 1936 Sir Thomas Inskip was appointed Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence and undertook the task of rearming Britain in the face of the German threat.

In 1936 as a part of the process of rearming and increasing the size of the RAF, the existing Command system was overhauled and four new functional Commands were formed: Fighter, Bomber, Coastal, and Training Commands. In 1937 Inskip reviewed the issue of the control of Naval flying once more and the ‘Inskip Award’ of 21 July 1937 transferred the Fleet Air Arm, with effect from 24 May 1939, back to the control of the Admiralty.

At the beginning of the war the RAF was still far from ready. Fighter Command was still replacing its old biplanes with the new Hurricanes and Spitfires and Bomber Command had 23 operational bomber squadrons, with 280 aircraft – mostly medium-range light bombers such as the Bristol Blenheim.

Adding to the RAF’s problems was the need to implement new technology to help aircraft defend and navigate. Early bombing raids were often imprecise, even in daylight, and fighter squadrons needed to receive early warning of enemy bomber raids in order to mount a defence. By 1940, however, the first chain of 20 air defence radio direction-finding stations (RDF, later called radar) were in place, operated by Fighter Command.

As the conflict became inevitable, the Air Staff were hopeful that a bombing campaign against Germany would lead to success in the war. The plans they laid down, however, were more optimistic than realistic given the insufficient numbers of available bombers, the unsuitability of current types to wage this sort of war and the fact that most of the potential targets were beyond the range of the bombers available. The importance of these plans in the long run was identifying strategic targets such as road and rail links between Germany and the front as well as German industry in the Rhineland and the Ruhr.

It soon became clear that Bomber command could not hope to fulfil the plans unless they were equipped with long-range heavy bombers and had sufficient training in gunnery, navigation and all weather flying. Without these the RAF’s early bombing raids were subject to disastrously heavy losses.

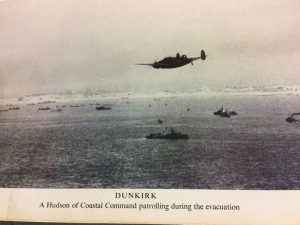

The RAF achieved its first significant defeat of Luftwaffe forces during Operation Dynamo when they provided air cover for the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk. Despite much criticism of the limited support they could give, Prime Minister Winston Churchill said: ‘Wars are not won by evacuations. But there was a victory inside this deliverance, which should be noted. It was gained by the Air Force.’

The Battle of Britain (10 July – 31 October 1940) was intended to set the stage for German invasion of Great Britain however the RAF squadrons, radar operators and all of the associated controllers, spotters and other crew produced a victory that ranks amongst Britain’s most significant. Again Prime Minister Winston Churchill had the words for it: ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’. This success is owed not only to the fighter pilots who flew their Hurricanes and Spitfires against incoming bombers but also to anti-aircraft guns and the invaluable chain of radar stations, the communications network and the control rooms that allowed them the necessary time to ‘scramble’ their aircraft into the air and find incoming enemy.

Alongside the ‘few’ Bomber Command played a significant role at this time, conducting strategic bombing raids against German targets as well as against the flotilla of landing craft that was being assembled in channel ports for Hitler’s ‘Operation Sea Lion’ invasion of Britain. The Battle of Britain lasted from 10 July until 31 October 1940 and merged into the period of large-scale night bombing raids, the Blitz, which lasted from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941.

Operation Sea Lion was ‘indefinitely postponed’ by Hitler on 17 September 1940 as his battle for air supremacy continued to prove unavailing.

The RAF, both Fighter and Bomber Command, continued to provide vital support to Allied forces. Bomber Command’s increasingly successful raids against the enemy were carried out by long-range heavy bombers such as the Avro Lancaster, Bristol Beaufort, Short Stirling and the fast and agile de Havilland Mosquito light bomber. Despite improved aircraft Bomber Command suffered the highest casualty rate of any of the allied services.

The RAF played a role in many different theatres of the 1939-45 war including the Mediterranean, Africa, and the Far East.

In 1941 a new era in UK aviation dawned when the first experimental British jet flew. The Gloster E.28/39 was the forerunner of the Gloster Meteor, which was operational by 1943 – the first jet fighter on the allied side.

Initial planning for Operation Overlord and the D-Day Landings began in January 1943 and General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s base, Camp Griffiss, in Bushy Park became the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), the centre for planning Operation Overlord and the D-Day Landings.

The RAF’s role in D-Day was mainly to join with the Allies to continue the bombing campaign against the enemy in preparation for the invasion. During ‘Big Week’ in February 1944 Allied attacks against the German aircraft industry drew out the German defences and resulted in the loss of 600 Luftwaffe fighter planes. Over succeeding months further large losses amounted to another 800. In all between February 1944 and April the Luftwaffe lost over 1,000 pilots and a large part of their air strength.

When D-Day finally came in June 1944 the Germans had some 700 serviceable aircraft of which only about 400 were fighters against which the Allies could place 1,408 bombers of RAF Bomber Command, 1,520 Bombers and 2,840 fighter-bombers from the RAF’s 2nd Tactical Air Force and 2,788 bombers and 1,242 fighters of the US 8th Air Force. Under General Eisenhower the deployment of all allied air forces was unified and focused on supporting land based operations and this unified control made a great contribution to the success of Operation Overlord.

In the post war years the RAF has continued to play a crucial role in national defence, search and rescue and British operations overseas. The Berlin airlift (June 1948 to September 1949) was the first major action of the Cold War and the RAF was an active participant. Up until 1998 the RAF’s V Bomber squadrons were an important part of the UK’s nuclear deterrent.

As the British Empire was evolving in the post-war era, the RAF was engaged in many parts of the world including the Arab-Israeli war in 1948, Malaya (Malaysia) in 1948, Kenya in 1953-54 and Suez in 1956.

In 1982 the Falklands War erupted and included significant participation by the RAF’s aircraft including helicopters, reconnaissance and refuelling aircraft, Vulcan and Victor bombers and Phantom and Harrier fighters alongside Fleet Air Arm’s helicopters and Sea Harriers.

In August 1990 the army of Iraq invaded Kuwait and began the Gulf War. A coalition of nations deployed forces into the area including the United States, the UK, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The RAF sent Jaguar GR1As, F3 Tornados, Tornado GR1 aircraft as well as Blackburn Buccaneers.

Since then, the RAF has contributed to NATO operations in Romania, Lithuania and Estonia, Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia, as well as taking part in military actions in Libya, Mali, Sierra Leone, and humanitarian missions in Congo, Nepal, Lebanon, the Caribbean, Pakistan and Kashmir, Cyprus, Nigeria, Kenya, West Africa and the UK.

To discover more about the history and heroes of the RAF there are many fascinating books in our libraries and we’ve gathered a fabulous selection for you to choose from on our Pinterest Board

Bibliography and further reading:

The Royal Air Force; an illustrated history by Michael Armitage

Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918 by Owen Thetford

Women in Air Force Blue by Squadron Leader Beryl E. Escott

Wings: the RAF at war, 1912-2012 by Patrick Bishop

Royal Air Force 1939–1945 (in three volumes) by Hilary St. George Saunders

Thoughts on Military History: The Royal Air Force and the Problems of the Inter War years (Dr Ross Mahoney’s blog)

Gale NewsVault (online newspapers)

[Elaine McClelland, Library Assistant]