Pulp Fiction: sex sells

Welcome to our new series on pulp fiction – the literature, not the film. To end LGBTQ+ History Month, today we’re looking at gay, bisexual, trans, and particularly lesbian pulps.

What is pulp fiction?

Pulp fiction strictly speaking refers to cheap stories printed on “pulp” – very low grade paper that was designed to be thrown away once the stories were read. This paper would quickly begin to disintegrate, showering the reader with flakes. Despite being known for their bright, attention-grabbing cover art, pulp paper was too coarse to hold much detail and illustrations of the actual stories were limited to crude, black and white line drawings.

Starting with the magazines that grew out of penny dreadfuls (in the UK) and dime novels (in the USA) – as well as fiction in other countries where pulp became popular – pulp fiction transitioned to cheap and plentiful paperback novels in the 1930s and 1940s. Paperbacks had become a publishing phenomenon linked to portability thanks to Allen Lane and his founding of Penguin books. While not necessarily “pulp” in material, these books were cheaply produced, covered in eye-catching wrappers and filled with often poorly-written stories designed to entertain. Full of sex, murder, violence, drugs and all the other anxieties of a post-war society, this phenomenon became linked in the public consciousness with “pulp” as much as the fiction magazines.

Queer sensibilities

Romance and sex had always been a key feature of pulp stories, particularly in the magazines dedicated to love stories. As paperbacks became more common and widely produced, reprints of books were a great way to both produce tried-and-true literature in a way that appealed to the masses and to get quick content. Far from the dedicated bookstores displaying high quality hardcovers for the moneyed classes, the lurid covers of pulp paperbacks were stuffed in to displays in drugstores, train and bus stations, news stands; anywhere they could be found and bought on a whim with the change in your pocket.

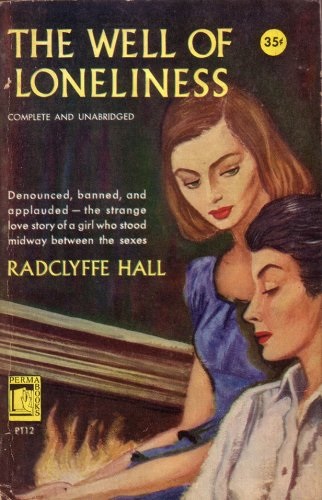

A few gay authors had already begun to break in to the literati in the first half of the 20th century, often helped by middle- or upper-class backgrounds and books that perfectly captured the sense of alienation felt by many in the post-war years. Surrounded by the acceleration of science, the changing pace of life and the nuclear threat that hung over the world, particularly the US, these books held great appeal. Reprints of books from gay authors that didn’t necessarily have explicitly gay content were popular. Books with lesbian content were also the topic of reprints, particularly books form Europe printed in the USA. Books like Radclyffe Hall‘s The Well of Loneliness – banned in the UK until 1949 – allowed US publishers to tap in to a hunger for scandal while also getting around issues of morality by linking lesbianism to a harmless past Europe.

Lesbian pulp

As the decades wore on, paperback originals (or PBOs) became more common. Publishers realised the immense hunger of the public for cheap books, fed by the ease of acquiring them and in the US the paperbacks provided to the Armed Forces for free during wartime. A public phenomenon of a very private act – that of reading – paperbacks explored topics that big movies and respectable, hardback literature either couldn’t or wouldn’t. They were also cheaper, more accessible, and more portable. This led to an increase in paperback originals, books written for the paperback market, often by authors who never would have been published in hardback. While a small number of novels with gay themes or by gay authors were published as PBOs, most gay content was in side characters who displayed the increasing visibility of gay men without explicitly treating it as a topic worthy of an entire story. However, the late 1940s to the 1960s saw a boom in lesbian paperbacks.

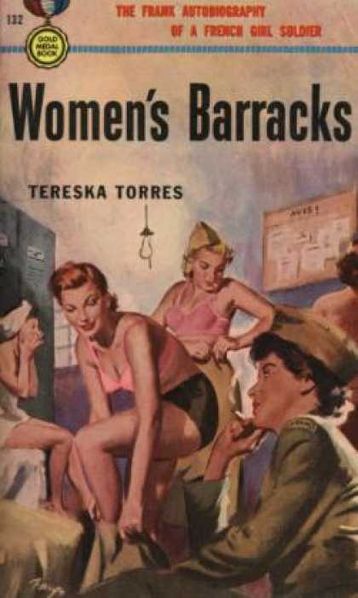

Books with explicit or implicit lesbianism were easier to get past the censors as titillation for a heterosexual male audience. Indeed, a huge number of lesbian paperbacks of the time were written by male authors who had likely never even met a lesbian, and certainly not considered the lives of those they were using for cheap sexual thrills. However, in 1950 Fawcett published Women’s Barracks by Tereska Torres, based on her time in London with the Free French Army during World War II. The book featured the lives of women living together, including some lesbian relationships. While very tame by today’s standards, the book was investigated as obscene by the Gathings Committee. Between the investigation and the book’s enormous success, publishers realised that they could sell lesbian literature to the masses and began publishing books by and about lesbians.

Unhappily ever after

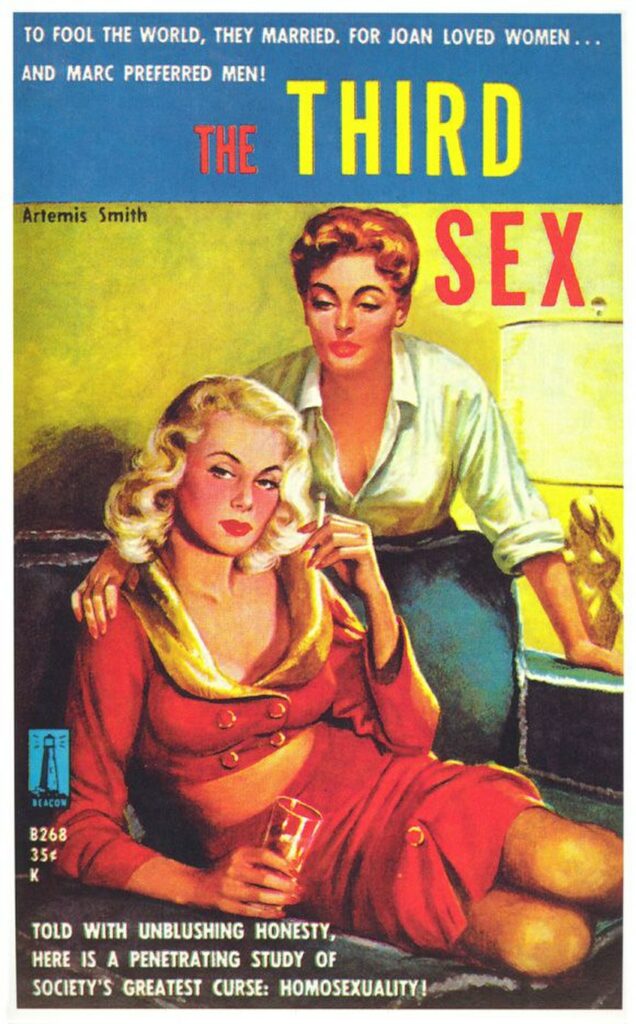

Lesbian pulps became a phenomenon of their own. While gay male books remained rarer due to being viewed as pornographic, bisexuality was limited to depictions of confused victims or sexually insatiable villains, and trans issues were ignored or treated as twisted pathologies of murderers and repressed homosexuals, lesbian literature flourished across the US. However, the censors still had to be avoided. The US Postal Service would seize any books it thought of as “obscene,” which could cover a broad spectrum, particularly when it came to sympathetic depictions of “abnormal” sexuality or gender expression. While it is not true that all books with gay themes had to end in death and horror, authors knew – and were often instructed – not to show a life of contented happiness between their gay, and particularly lesbian, characters. Death, madness, and suicide were all common endings. So were characters being suddenly “fixed” and ending up in a heterosexual relationship, or at least alone with the understanding they must fight their “perversion.”

Cover text was also an excellent way to moralise about a book’s content. Often, the more sensitive and humanising the depiction of lesbians and other non-straight characters within a book, the more scathing and panicked the cover text. Covers proclaimed voyeuristic looks into shadowy worlds of perversion; boundary-pushing explorations of the mysterious “third sex” (homosexuals); and novels that had to be read in order to understand (and stop) the “blight” of lesbianism sweeping the nation. Not only a way to get around the censors, the covers also served as a warning for any women reading the books – you may identify with these characters, but don’t forget that they are perverse, degenerate, and you must strive not to become like them at any cost.

Gender roles

The 1940s and 50s was a time of great cultural change in many parts of the world, and certainly in the US a time of great cultural insecurity. In the UK traditional gender roles had been called into question as woman went to work during the war, and a sudden need to entrench gender roles even as they were called in to question bled over to the US. This gendered anxiety found expression in pulp novels, with violent misogyny, simpering femininity and ultra-sexualised femme fatales all key features of many genres of pulp.

However, this fascination with gender was also shown in the attitude towards sex changes, cross dressing and – in the later decades, particularly as the sexual liberation of the 1960s gathered pace – drag queens and other gender bending aspects of gay culture. Fiction with trans themes tended to be sensationalist and bigoted, using cross dressers and transexuals as a cheap and titillating twist. However, non-fiction books about trans people were also popular in paperback. After the widely publicised sex change of Christine Jorgensen, which became front page news in 1952, the public’s appetite for these stories led to numerous paperbacks on other trans stories. Reprints of Lili Elbe‘s biography and a number of similar paperbacks followed. While many of these were purely voyeuristic condemnation, there were sensitive treatments of trans issues, often autobiographies written under pseudonyms.

Culture waves

Paperbacks were everywhere. While they reflected anxieties and increased visibility of LGBTQ+ people, they also reached people cut off from the scene in larger cities like San Francisco. The drugstore paperback reached small towns in a way bar culture could not, giving isolated lesbians, gays and bisexuals language for their feelings and teaching them that they were not alone. In particular the proliferation of lesbian paperbacks provided a kind of informal education for young lesbians – this is who we are, how we dress, where we exist, how we love. Featuring gay and lesbian storylines at a time when they could not be seen in other mass media brought issues to the mainstream in a way that may not otherwise have happened. It has been argued that this proliferation of paperbacks, objects that certainly both reflected and shaped cultural psyche in many other ways, also contributed to the gay rights movements – including the Stonewall riots.

Whatever effect they had on the individual and society at large, the pulp paperbacks of the early- and mid-twentieth century are certainly a hugely important part of LGBTQ+ history, and in many cases a great read.

Book suggestions:

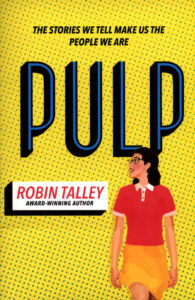

This YA novel links a modern girl researching lesbian pulp fiction, and the story of lesbian pulp fiction author in the 1950s.

Originally published as The Price of Salt, Carol was issued as a cheap paperback in the early 50s and is widely regarded as the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. A resurgence of interest has followed the 2015 film adaptation.

Leave a Reply