Richmond Palace – [Local History Notes: 11]

Henry VII built Richmond Palace on the site of the former Palace of Shene which was severely damaged by fire when the king and his court were there for Christmas 1497. Henry I had first divided the manor of Shene from the royal manor of Kingston and granted it to a Norman knight. It returned to royal hands in the reign of Edward II and after his deposition it was held by his wife, Queen Isabella. After her death Edward III extended and embellished the manor house and turned it into the first Shene Palace where he died on 21st June 1377.

Henry VII built Richmond Palace on the site of the former Palace of Shene which was severely damaged by fire when the king and his court were there for Christmas 1497. Henry I had first divided the manor of Shene from the royal manor of Kingston and granted it to a Norman knight. It returned to royal hands in the reign of Edward II and after his deposition it was held by his wife, Queen Isabella. After her death Edward III extended and embellished the manor house and turned it into the first Shene Palace where he died on 21st June 1377.

His successor, his grandson Richard II, was only a boy when he came to the throne. As a teenager he was married to Anne of Bohemia and the young couple turned the dynastic marriage into a love match. Shene was their favourite home. Anne died of the plague at Shene on Whit Sunday 7th June 1394 and, stricken with grief, the king ordered the complete demolition of the buildings.

Henry V determined to rebuild Shene He first had the, mostly timber, royal manor house at Byfleet demolished and moved to Shene as temporary quarters, then proceeded to begin the construction of a massive new castle-like building. His death in 1422 put a stop to the work. Henry VI was only a baby, but the King’s Council resumed the building work at the time of his coronation when he was 8 years old. Further enlargement of the palace was put in hand in the mid-1440s when the king was married. By about 1450 the palace occupied the full site of the later Tudor one. Edward IV gave Shene manor to his queen, Elizabeth Woodville and she held it until shortly after the victory of Henry VII over Richard III and then handed it over to the new king – who married her daughter, Princess Elizabeth of York.

Henry VII’s Building

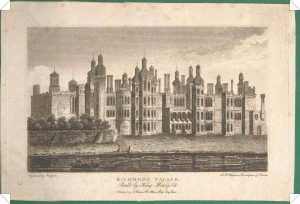

After the fire of 1497, Henry wanted to rebuild the palace. The fire had probably not destroyed the whole Privy Lodgings block, where the royal apartments were situated, for the new palace adopted the same ground plan as the buildings of Henry V and VI. The Privy Lodgings, on the side facing the river, still had much of the appearance of a 15th century castle. Built in white stone, it had many octagonal or round towers capped with pepper-pot domes or cupolas (with delicate strapwork and decorated weather vanes). The building was a rectangular block of three storeys with twelve rooms on each floor, built round an internal court of 24 x 40 feet and its southern side about halfway down what is now the lawn of Trumpeter’s House. Despite its name, the rooms in this building were both staterooms and private royal apartments, while the ground floor was entirely given over to accommodation for palace officials.

A bridge over the moat, surviving from Edward III’s time, linked the Privy Lodgings to a central courtyard some 65 feet square, flanked by the Great Hall and the Chapel and with a water fountain at its centre. The Great Hall was 100 x 40 feet, built of stone, roofed with lead and supported on an undercroft used as a buttery and other offices. It had a large brick hearth in the centre and a louvred lantern in the roof to let out the smoke, but there were also two fireplaces with chimney flues. It had a fine open hammer-beam roof structure.

The Chapel, also of stone, measured 96 x 30 feet internally and was lavishly decorated. Beneath it were the wine cellars and above them a floor devoted to rooms for officials. At each side were flanking buildings containing privy closets for the king and queen, with windows opening into the Chapel. The Chapel had a ceiling of chequered timber and plaster decorated with roses and portcullis badges. A gallery building linked the Hall and the Chapel at the south side of the Fountain Court and gave access to the bridge. At the north side of the court another two-storey building of stone contained apartments for senior courtiers and the middle gate of the palace, turreted and adorned with the stone figures of two trumpeters.

This gate opened into the Great Court which had red brick buildings on the east, west and north sides. On the east was the palace wardrobe where the soft furnishings were stored; on the west were rooms for officials and courtiers; the north had more such apartments and the main gateway out onto the Green. (the upper storey over the gateway was not added until the 1590s.) The range of double-storey brick-built apartments – with half turrets at intervals along the outer wall – extended for almost the full length of the frontage facing the Green, though at the eastern corner a flat stretch of wall covered the open tennis court.

The domestic buildings to the west of the Great Hall were dominated by the pyramidal louvred roof of the great Livery Kitchen in which the courtiers’ and officials’ meals were prepared – the royal family had their own ‘privy kitchen’. Between these buildings and the river was the Great Orchard. A side passage led out of the Great court, by these buildings, to the ‘Crane Piece’, a piece of open land beside the moat stretching down to the riverside, where a crane stood to unload the goods and provisions brought by water to the palace.

On the east side of the main buildings were the palace gardens, encircled by two-storey galleries, open at ground level and enclosed above, where the court could walk, play games, admire the gardens, watch the tennis etc. Such galleries were a new feature of English palace plans.

In 1501 the king, having ‘rebuilt it up again sumptuously and costly…changed the name of Shene and called it Richmond, because his father and he were Earls of Richmond’ [in Yorkshire].

For a while Richmond Palace was the showplace of the kingdom. The celebrations after the wedding of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon were adjourned from London to Richmond in 1501; the official betrothal of Princess Margaret to King James of Scotland took place there in 1503. In 1509, Henry VII died in the palace he had built.

The Palace from 1509 to 1650

Henry VIII promptly married his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, and in 1510 Catherine gave birth at Richmond to a son, Henry. There were great celebrations when he was christened at Richmond, but he died a month later. Catherine produced only one child who survived, Princess Mary.

Cardinal Wolsey, the king’s chief minister, had built Hampton Court – a palace which overshadowed Richmond. About 1525 Wolsey came to an agreement with Henry which amounted to their sharing the two palaces, with Hampton Court to become Henry’s on Wolsey’s death. Wolsey’s failure to arrange a quick divorce for the king from Catherine led to his downfall and death in 1530. Richmond now became a home for discarded queens – first for Catherine and her daughter Mary while Henry courted and married Anne Boleyn. Later it was given to Anne of Cleves as part of her divorce settlement.

Both Mary and Elizabeth made more use of Richmond during their reigns. Elizabeth was particularly fond of Richmond as a winter home – perhaps the relative compactness of the Privy Lodgings building made it easier to keep warm. She frequently visited Richmond at Christmas and Shrovetide and enjoyed having plays performed for her in the palace by companies of players from London. – including the one of which William Shakespeare was a member. Elizabeth died at the palace on 24th March 1603.

James I gave Richmond to his eldest son, Henry Prince of Wales, as a country seat. Henry had great plans to remodel the gardens – and even the palace itself – in accordance with the latest continental fashion. But he died in 1612 before much work had been done. After an interval of some years, Prince Charles (later Charles I) took over Richmond, but although he continued to build up the art collection which his brother had started, he had no plans for architectural improvements. When he became king, Richmond Palace was once again used as a home for the royal children until the Civil War.

The End of the Palace

After Charles I’s execution, Richmond Palace was sold by the Commonwealth Parliament along with most of the royal real estate throughout the country. The purchasers of Richmond divided up the palace buildings. While the brick buildings of the outer ranges survived, the stone buildings of the Chapel, Hall and Privy Lodgings were demolished and the stones sold off. By the restoration of Charles II in 1660, only the brick buildings and the Middle Gate were left. The palace became the property of the Duke of York (the future James II) in 1669. Many of his children were brought up there including his daughters Mary and Anne – both future queens – but his sons died. When he became king and had a last and surviving son, Prince James Edward (the ‘Old Pretender’) who was nursed at Richmond, James started to do some repair and restoration work on the palace under the supervision of Christopher Wren; but his deposition and abdication in 1689 put a rapid and premature end to the work.

The remains of the palace were leased out to various people and, in the early years of the 18th century new houses replaced many of the crumbling brick buildings. ‘Tudor Place’ had been built in the open tennis court as early as the 1650s, but now ‘Trumpeters’ House’ was built in 1702-3 to replace the Middle Gate, followed by ‘Old Court House’ and ‘Wentworth House’ (originally a matching pair) in 1705-7. The Wardrobe building had been joined up to the Gate House in 1688-9 and its garden front was rebuilt about 1710. The front facing the court still shows Tudor brickwork as does the Gate House. ‘Maids of Honour Row’ replaced most of the range of buildings facing the Green in 1724-5 and most of the house now called ‘Old Palace’ was rebuilt about 1740.

Further Reading

Cloake, John / The existing remains of Richmond Palace in Richmond History No. 2, December 1981, pp. 8-12

Cloake, John / Richmond Palace: its history and its plan. Richmond Local History Society. 2000

Fletcher, Maj. Benton / Royal Homes near London. 1930

Asgill House, Richmond – [Local History Notes No: 9]

Richmond Green – [Local history Notes: 36]

Richmond Green: Properties – [Local History Notes: 37]

Maids of Honour Row – [Local History Notes: 50]

Trumpeters’ House, Old Palace Yard, Richmond – [Local History Notes: 51]

Cholmondeley Way, Richmond – [Local History Notes: 57]

Queen Elizabeth I at Richmond – [Local History Notes: 60]

Thurley, Simon / The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: architecture and court life 1460-1547. 1993

Way, Thomas R. and Chapman, Frederic / Ancient Royal Palaces in and near London. 1920

Williams, Neville / The Royal Residences of Great Britain: a social history. 1960

We acknowledge the work of Dr. John Cloake in writing this Local History Note

More information on other places and people of interest in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames is available from the Local Studies Library & Archive.