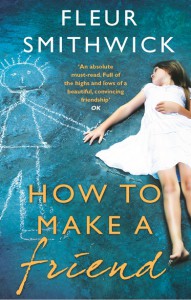

Interview with local author, Fleur Smithwick

Fleur recently appeared in conversation at Hampton Hill Library talking about how she wrote and published her debut novel, which is a psychological thriller called How to make a friend. In the novel, the protagonist – 26 year old Alice, suddenly finds that her childhood imaginary friend Sam has reappeared after a traumatic accident…

It was a great evening at the library and the sold out event was very much enjoyed by all who attended. Fleur has kindly agreed to publish the questions from the evening and short versions of her answers here on the library blog for those who couldn’t make it on the night.

1. Can you tell us what How to Make a Friend is about?

Alice, the youngest of three children from a broken home, is a lonely and emotionally neglected child caught between the narcissism of her mother and the indifference of her siblings. As a child she has an imaginary friend called Sam. When the story begins she is twenty-six years old, has a successful career in photography, enjoys a good relationship with best friend Rory and is deeply in love with his older brother Jonathan. When Alice survives a horrific car accident, Sam returns to assume the role of protector. He shields her but he also ruthlessly manipulates her insecurities to increase her dependence on him. When Sam realises how involved she is becoming with Jonathan, he becomes dangerous.

Alice needs to regain control of her own mind and keep her friends from harm. But is it Sam, or is it Alice who presents the real danger?

2. Did you ever have an imaginary friend as a child, if so, what was their name and what were they like?

I did. His name was Eddie. Unlike Sam he didn’t actually do anything. He was more an object to talk to in my head when I was on my own. I didn’t fit in at school – I had that intangible thing that repelled other children. I spent a lot of time in daydreams completely cut off from what was going on around me. I still do sometimes, although obviously not with an imaginary friend.

3. Can you tell us a bit about your two main characters, Alice and Sam?

When I wrote Alice, I took myself back to my childhood. I didn’t have a dysfunctional family, but otherwise the young Alice is very much drawn from experience. What was important to me, when I was writing the novel, was to find a story that showed that you can start out as a weird and socially-inadequate child, and grow into a fully-functioning adult with friends, family, kids: the lot. But also that there is absolutely no point blaming others for what’s happening, you have to work it out for yourself and put it right yourself. I’d love to be able to tell that child that it does get better; that, with strength of mind, ruts can be climbed out of.

Alice is attractive, has friends and is at the beginning of a career as a photographer. She’s tenacious but vulnerable at the same time. Her childhood has never left her, and her fear of loneliness is ever present. When Sam arrives she doesn’t realise at first that this is something she has to fight and her acceptance of him, leaves her open to abuse by him. When she starts to fight, it’s almost too late.

Sam is melodramatic and although at first he seems sympathetic, he never does anything that doesn’t have himself and what’s good for Sam at its root. People like this have always fascinated me; huge egos coupled with what seems on the surface generosity of spirit, but is in fact something quite else. Sam wants to survive, but not just to survive. Like Pinocchio, or even King Louis in The Jungle Book, he wants to be real.

4. How to make a friend is a love story and a spine-chilling thriller at the same time. When you started writing, had you already decided that Alice’s story would take a very sinister and creepy turn?

I didn’t, because the novel’s genesis was a short love story. It was when I started turning it into a novel that it quickly became obvious that the love story wouldn’t be enough to sustain it. At the same time Sam’s character was growing and his need to be acknowledged was becoming the spine of the book. Even so, I didn’t mean it to turn out as dark and creepy as it did! People’s reactions surprised me at first but I am very happy with that development.

5. The title of the book is obviously a play on the word ‘make’ but who decided on the title and why?

The choice of title was mine. The original story was called Play On and I loved that and still do. However I was told it didn’t say anything about the book. To my mind neither does How to Make a Friend! For a while it was called The Watchman, which comes from the quote in the Epilogue:

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake;

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat

To play the watchman ever for thy sake.

William Shakespeare : Sonnet 61

I thought the title would be the easy bit, but that wasn’t the case. I had lists and lists!

6. Your choice of narrator shifts to that of the imaginary friends in the prologue and epilogue. What gave you the idea to bookend the novel in this way?

This to me was a reminder of where the book began. The original short story was told entirely from the point of view of Sam – you can get away with anything in a short story. I don’t know whether it was a good decision to have them or not, but I love them.

7. There is an interesting idea around the contagious nature of loneliness that runs through the book, i.e. that others can see it on you like a miasma and avoid you as a result. Was that a deliberate theme?

Miasma is a great word. I’ve thought more and more about this. I do have a fear of loneliness and can so vividly recall what it felt like. It could make me feel physically ill. It’s been a long time since I’ve had an episode when I’ve felt that completely alone, and sick with it, but it’s something that will never leave me.

I actually enjoy being on my own; I walk on my own; I fantasize about having the house to myself for a day. It’s the unexpected and unprepared for aloneness that scares me. Particularly being alone amongst people. I’m sure everyone’s experienced this on some level. The child in the school playground, the stranger in the big city, the odd-one-out at a party. I’ve come to realise that you can learn how to deal with this and teach yourself strategies, but it’s very hard, particularly for children. I have certain rules for myself which work well. It’s a question of puncturing that miasma and realising that others are feeling it too and are far more likely to welcome a friendly approach than reject it.

8. Do you have any advice for aspiring psychological suspense writers? Can you tell us anything about psychological suspense as a genre?

This is a huge subject on which I have many thoughts. However, as someone who has attempted different genres without success only to finally break through with a novel that actually avoided genre, I will say that you cannot go into it cynically. You have to work out what it is you want, how you feel, what story you want to tell and tell it your way.

Psychological Suspense is a vast subject and a label that publishers are applying somewhat indiscriminately because it is selling well at the moment. Of course there are certain things that are expected by readers and editors looking for a particular experience, but they still want something new and original. There is no point trying to write the next Gone Girl. Write your book for yourself first and foremost. Your take is what makes it original.

Having said that, here are a few tips to get you started:

- Limit your focus and characters as far as you are able. Read a few older books that do this, as well as contemporary bestsellers. Good examples would be Rebecca, and Stephen King’s Misery.

- Be inside your character’s head. The reader has to feel what they are feeling and experience everything with them as they are experiencing it. It must feel immediate. The first person point of view helps here, but you have to be careful not to let the ‘I’ sentences build up and become repetitious and dominating.

- Build up tension, throw in surprises and lead up to a thrilling ending. You don’t have to have a body at the beginning – (up to you of course). The problem with opening with a body is you run the risk of it becoming a police procedural.

It helps if your protagonist has as much of an internal battle as an external one. So fighting her own particular problems as well those thrown at her. - Psychological suspense often starts in a world of domesticity, of marriage and children, cookbooks and school runs. I enjoy writing about ordinary, reasonably sensible women who become derailed; women who begin by blaming external forces and have to learn that it starts with them.

There is a lot more I could say on the subject – I love talking about it – but if you are getting started it is important to read what’s out there already, but equally important to ignore it once you’ve absorbed the lessons. Find your unique voice and do it your way.

9. Are you working on a second novel? If so, could you give us a little preview?

My next novel is at the final edit stage. It’s called One Little Mistake and is about a mother who decides on the spur of the moment to slip out of the house while her baby is sleeping. She’ll only be twenty minutes and he never wakes up during his morning nap, so what harm can it do?

A great deal of harm as it turns out. Her closest friendship, her marriage, her family and ultimately her life, come under threat. Lies are told and secrets are kept at a price.

Fleur can be contacted via her website: www.fleursmithwick.com