Fire and flood: the saga of Richmond Lending Library

As those who use it know, Richmond Lending Library is currently closed for repairs. All of our library buildings need upkeep, and buildings sometimes close for longer to allow for more extensive refurbishment. This keeps your library services modern and up-to-date, in attractive and useful buildings. However, the current project going on inside Richmond Lending Library is a little different to the normal repair works.

Anyone familiar with world literature or mythology knows of epic flood myths, but over the past few years Richmond Lending Library has had its own floods to contend with. Occasionally, when the rains are heavy and the gutters get blocked, the library itself floods and staff must battle the deluge to rescue any books that might get damaged. Rain indoors is an unusual occurrence anywhere, but it is particularly problematic for a library building. How did this happen?

A library is born

The building we know as Richmond Lending Library opened on 18th June 1881. It was not the first library in Richmond: that honour likely belongs to Henry VIII’s Palace library. Later, public libraries were provided – at a cost to members. However, following the Public Libraries Act of 1855 the people of Richmond held votes and meetings showing their overwhelming support for a free public library, support that has not wavered since.

The heartfelt reaction to the members the Vestry chose for the Library Committee demonstrates this support. The Vestry was the local government of the time, and do not seem to have supported the library. The Richmond and Twickenham Times printed a biting condemnation of the Committee by founder Edward King, a staunch supporter of setting up a free public library in Richmond. His furious reaction to the Committee reads:

“the Vestry … have, with pitiable bad taste, shown their spleen by electing, in hot haste, an executive, the majority of which is in avowed opposition or, indifferent to the liberal and intelligent application of the Acts to Richmond. How in the name of common sense can the Vestry expect the ratepayers to have faith in a Library Committee the majority of which, up to the time of their appointment, have been dead against the present application of the Acts? Are we to expect that at a moment’s notice they will twist right round, like well-oiled weather cocks, to an opposite opinion; and if not, why, by all that is just and manly, do they serve on the Committee at all?”

People in Richmond clearly shared King’s opinion that the Vestry had retaliated to the public vote by attempting to thwart the Library before it was even created. Ratepayers (tax payers) were added to the Library Committee following the backlash.

Building Begins

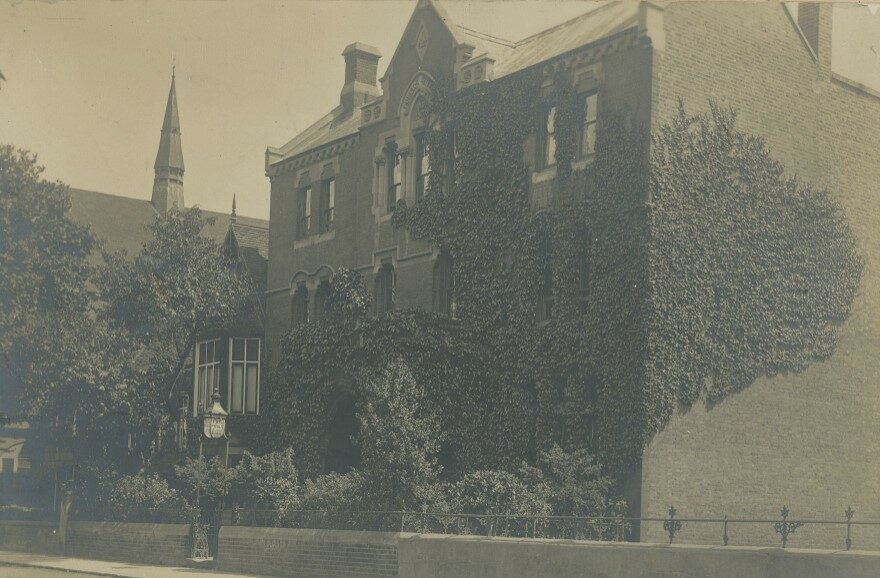

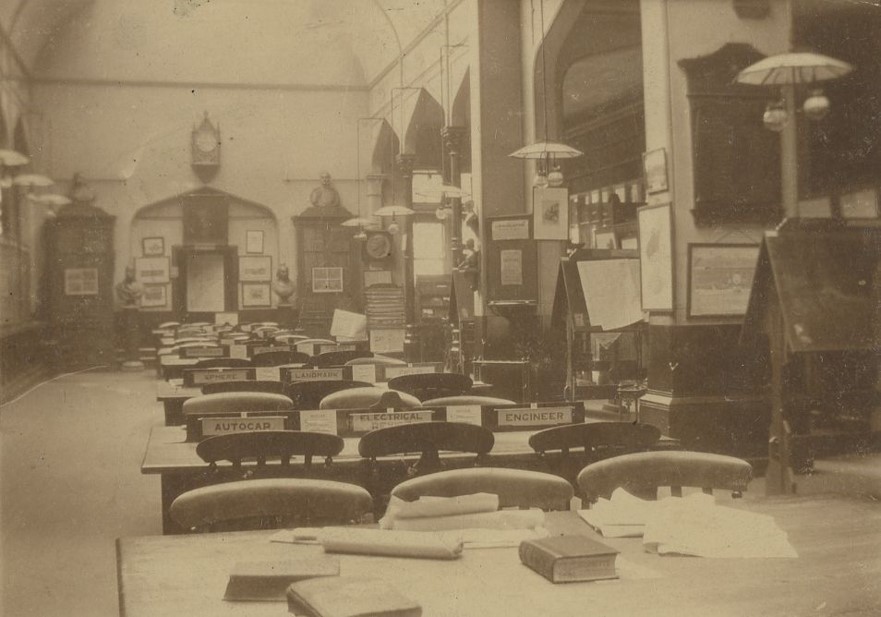

The building by Little Green was purpose built to house the Free Public Library. It included a newsroom, reading room, ladies’ room and office, and accommodations for the on-site librarian. The public’s enthusiasm for their library was immediate. Within 3 months the appointed librarian, Mr Cotgreave, was issuing 350 books a day and pleading for an assistant. An extension to the building of 45 feet (nearly 14 metres) opened on 3rd August 1886. In 1905 the house next door to the library was purchased as the new living quarters for the librarian; “The Cottage,” as it is known, is still used to house librarians (although only during the day). This purchase made space in the main library building for the Reference Library and the addition of children’s books.

Even this did not solve the issue of space. After the death of then-librarian Albert Barkas in 1921 it was decided accommodation would no longer be provided for the librarian and The Cottage became a lecture room and book store. More renovations were made to the library after one librarian, A. Cecil Piper, insisted the Lending Library introduce open access for the public; before open access, an individual had to request their desired book, which the librarian or assistant would get for them. The new open-access Library opened in 1924, including the first Children’s Library. Richmond’s Free Public Library was complete and open for use.

(Photograph held at Richmond Local Studies Library and Archive. Reference: LCF/4359)

Fire in the library

The library provided a dedicated service come rain, shine – or war. Piper, the librarian during the Second World War, was determined to keep the library open despite losing many of his staff to war service. Indeed, the library remained open and active throughout the entire war, with one notable exception.

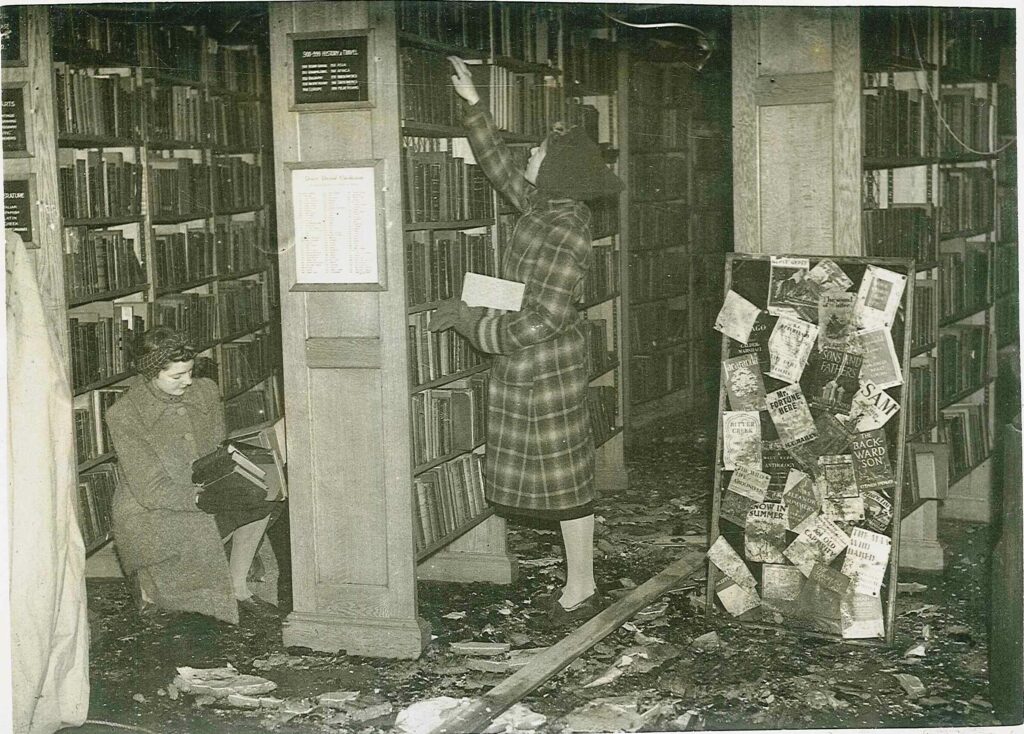

On 29th November 1940, disaster struck. Richmond’s town centre came under bombardment. The bombs whizzing through the air hit many buildings and left devastation in their wake; 27 people (including children) died, and buildings were destroyed. Amidst this horror an incendiary bomb struck the library. Although thankfully no-one was killed in the blast the library was damaged. The bomb set the roof on fire and books, newspapers, prints and maps suffered water damage, many of them from the treasured Local Studies collection started by Albert Barkas. These photos of the clean-up effort show some of the damage.

Despite this, the library was only closed for a single week before re-opening to the public. The only exception was the Newspaper Room, which re-opened in 1943.

The roof’s tale

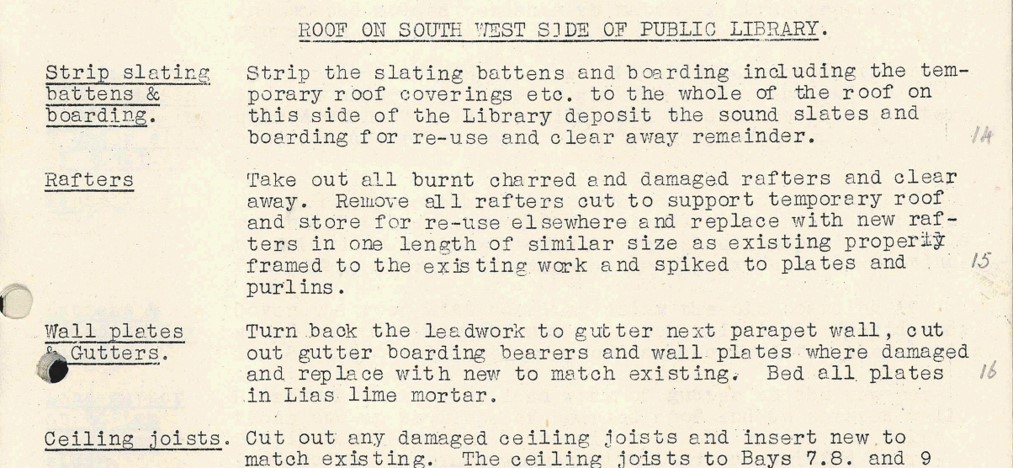

The roof itself was never comprehensively fixed after the bomb damage. In the haste to maintain access to this vital service at a time of crisis, a temporary roof was installed. After the war further attempts were made to ensure the roof was safe and sturdy. In 1946, works were carried out to try and repair some of the damage. However the 1946 work didn’t completely fix the issues with the roof.

This means that today Richmond Lending Library – the oldest library still in use in London – has a roof suffering from damage that happened the best part of a century ago. The exploratory works in preparation for the current restoration discovered blackened timbers in parts of the roof still bearing 80 year old scars from November 1940.

Now we are finally able to fully fix the roof. The wood that has been deteriorating will be restored, the poorly fitting glass will be made watertight again, and the roof will once more be fit for purpose protecting the libraries resources – and the public! – from the elements. Meanwhile, we luckily have a small space in Richmond Library Annexe where we have set up a pop-up mini library. Our other branches will also help compensate for the closure until the roof is fixed and the library is once again restored.

Links and further information

A map indicating the number of bombs dropped on Richmond upon Thames during the Second World War can be seen here.

You can read a more complete history of Richmond Library in the corresponding Local History Note.

Richmond Local Studies Library and Archive holds all the images reproduced in this post. If you own the copyright to any images and do not wish them to appear here, please contact us at libraries@richmond.gov.uk and we will remove them as soon as possible.

Leave a Reply