Artists at War: Paul Nash and the First World War

When war was declared on 4 August 1914 many artists – the profession was then still predominantly male – began to enlist. The Royal Army Medical Corp (RAMC), which provided first aid and medical care for the army, held a recruitment drive in the bar of the Chelsea Arts Club and thirty artists signed up as a result. The RAMC continued to be popular with artists and Stanley Spencer, for example, served on the Macedonian front as part of a Field Ambulance Unit.

Artists and the war

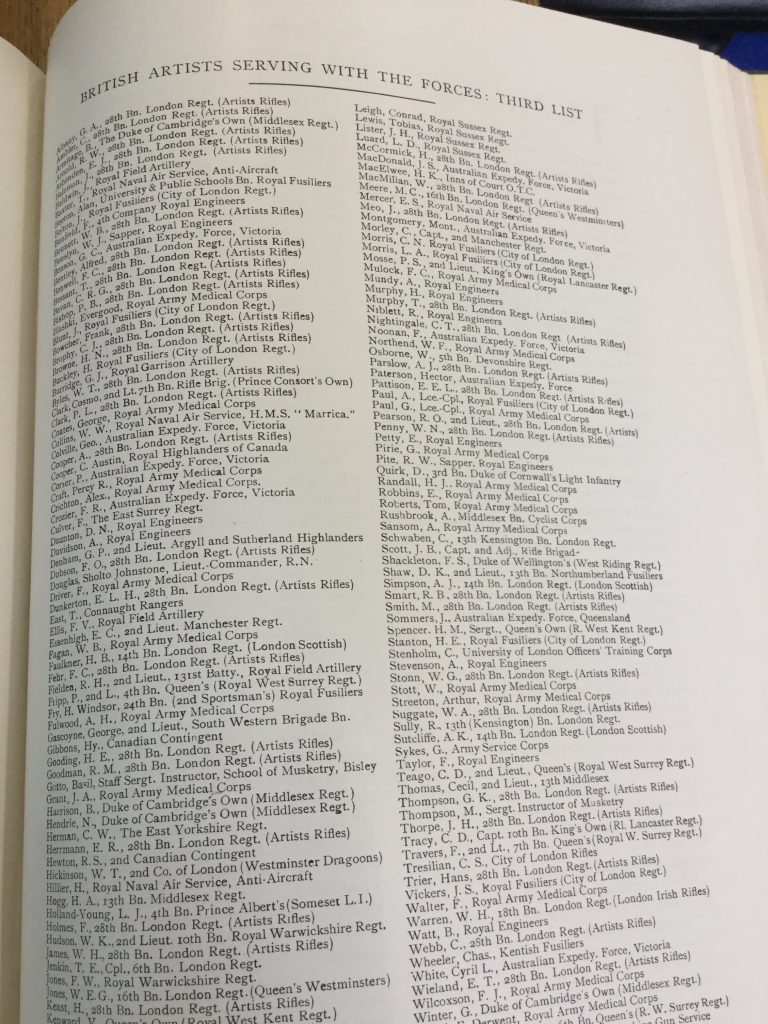

Many other artists joined the Artists Rifles*. It had been formed in 1860 by art student Edward Sterling when the potential threat of invasion by the French led to a wide volunteer movement. It attracted actors, artists, architects, poets, writers and musicians, and had its first headquarters at Burlington House, home of the Royal Academy of Arts. Its first commanders were the painters Henry Wyndham Phillips and Frederic Leighton. The regiment went on to become very successful at training officers and in early 1915 some NCOs and officers were selected to form an Officers Training Corps. Of the 15,000 men who passed through the ranks during the First World War more than two-thirds became officers. The battalion eventually saw battle in France in 1917 and 1918 and suffered higher casualties than those of any other battalion. Members of the Regiment won eight Victoria Crosses, fifty-two Distinguished Service Orders and nearly a thousand other awards for gallantry. Eventually, in July 1947 the Artists Rifles became the 21st Special Air Service Regiment (Artists Rifles), part of the SAS.

The Studio magazine, the influential art and applied art magazine, regularly published lists of artists who were serving with the forces.

Artists continued to draw and sketch while they were serving, snatching time between duties and sometimes struggling to keep their sketchbooks dry in the damp conditions of the trenches. Eric Kennington was one such artist and in 1915, while convalescing, he painted the Kensingtons at Laventie. This was painted using the unusual technique of oil paint on glass, and was based on his wartime experiences. It depicts the men with whom he served as an infantryman in the trenches – he can be see in the left of the painting wearing a balaclava. It was exhibited at the Goupil Gallery in May 2016 and caused a sensation. It is now in the Imperial War Museum. Kennington was eventually appointed as a war artist in August 1917.

Official War Artists

The Official War Artists scheme came out of the secret Foreign Office propaganda agency, known as Wellington House, which was established in late August 1914 and headed by the politician Charles FG Masterman. In April 1916 a pictorial division was set up to produce visual propaganda, such as war films, lantern slides, photographs and line drawings. They, as well as the national press, were eager for visual material as the limited flow of official photographs from the battlefields could not satisfy the demand. Newspapers even took to offering cash to soldiers who could produce sketches of the war they could use.

The first official war artist – appointed in July 1916 – was Muirhead Bone, the Scottish draughtsman and printmaker, who was already serving in the army. He had been approached by Masterman, who had heard that he was serving and wondered if he could produce work for the war effort; there were already similar schemes running in France and Germany. Bone’s drawings were published for sale, in ten monthly parts, from late 1916 and were priced at one shilling each. They were printed using the new photogravure process on newsprint. Bone championed the work of younger artists such as CWR Nevinson and Stanley Spencer both of whom were appointed to the scheme.

Artists were allowed considerable freedom. For example, Masterman told Nevinson that he could paint anything that he pleased. However, their work was subject to oversight by the official censors and artists themselves were careful not to depict anything that might be militarily sensitive.

In February 1917 the Department of Information was created under the directorship of John Buchan to bring together the different strands of allied publicity and propaganda. In March 1918 it was replaced by the Ministry of Information with the recently ennobled Lord Beaverbrook as its director. He had already successfully set up the Canadian War Memorial scheme** and his input changed the direction of the scheme from being a record of the war to that of creating a lasting artistic memorial for future generations. His intention was to hang commissioned works in a hall of remembrance. The British War Memorials Committee was set up and they commissioned artists to produce either a single piece of work (for £300 plus material and studio expenses) or they were paid £300 for a year’s worth of work.

Beaverbrook’s energy and clear purpose undoubtedly helped the success of the scheme but his dual role as a press baron and a peer were regarded as incompatible. He was envied and mistrusted by some in government.

The National War Museum (which was set up in 1917 and later renamed the Imperial War Museum to reflect the role of the Commonwealth countries) also commissioned work but in a more systematic way. The subjects covered included: the home front, all the services and women’s roles. There were tensions between the committee, the Museum and the Treasury and in July 1918 Beaverbrook resigned as minister. The whole operation then went over to the Imperial War Museum.

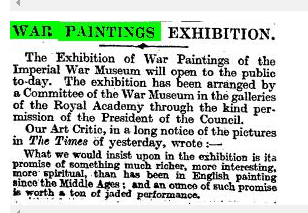

The Hall of Remembrance project was never realised, but the Imperial War Museum had, and still has, an unparalleled collection of work by contemporary artists depicting the war on all its fronts and in all its guises. In December 1919 a hundred of the three thousand works produced by the official war artists went on display in a Royal Academy of Arts exhibition.

Paul Nash

Paul Nash was 25 when war was declared. He had studied at Chelsea Polytechnic (the LCC art school at Bolt where the approach was more commercial – he undertook commercial work throughout his life) and also at the Slade for just over a year, where his contemporaries included Stanley Spencer and CWR Nevinson. Nash had already had exhibitions and was a member of The London Group.

On 10 September 1914 he joined the 28th Battalion London Regiment (Artists Rifles) for home service as he believed that he should first learn the job of being a soldier before becoming an officer. He served time as a map-reading instructor in Essex before he undertook officer training, and he was created a second lieutenant and joined the 15th (Service) Battalion of the Hampshires. Eventually, in February 1917, he found himself in France. Despite his duties Nash had time to explore the broken, landscape of Flanders and was surprised when he began to see nature returning and the battlefields becoming green again. He wrote letters to his wife, Margaret, describing what he saw.

Nash said at the time ‘… I believe I am happier in the trenches than anywhere out here. It sounds absurd, but life has a greater meaning here an a new zest, and beauty is more poignant.’

By early March 1917 Nash had despatched his first lot of drawings to his dealer.

Nash was to be in France for only two months before an accident (he tumbled on the battlefield at night) led to him breaking a rib and being sent home to convalesce. He used the time to work and in July 1917 he had a show of 18 drawings at the Goupil Gallery.

The show got him noticed, in particular by Edward Marsh, Churchill‘s Private Secretary, who used his influence to get John Buchan to send him back to the Front as one of the official war artists. So, in October 1917 Nash returned to Flanders as an officer with his own car and a driver who fearlessly drove him over the battlefields. Nash worked fervently, sometimes producing 12 – 20 drawings per day despite the difficulties of travelling near the front line. Paul Gaugh thinks that, ironically, he probably exposed himself to more danger working as a war artist than as an infantry officer

Early work

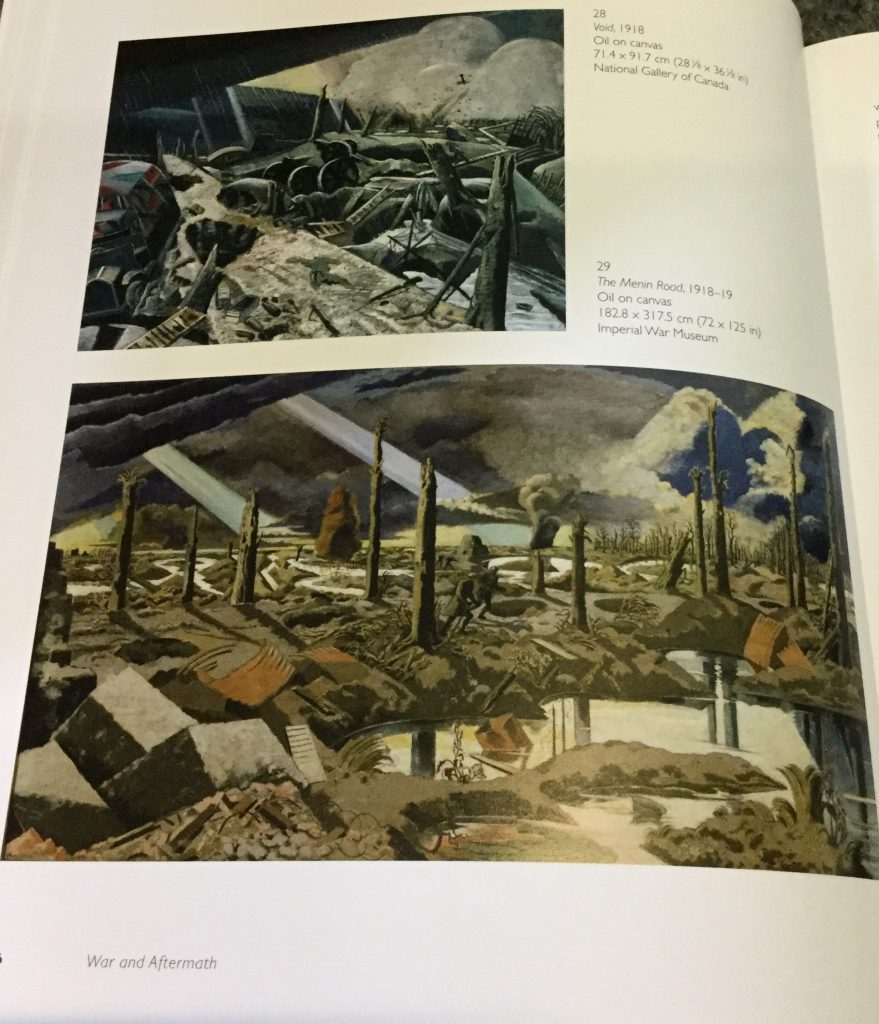

His early work, drawings and watercolours, were all of landscapes, and in particular trees, that Nash felt deeply connected to, and embodied Nash feelings about the spirit of the place, and his connection with the land and a sense of otherness and magic. Nash was following in the English mystical tradition of William Blake and William Palmer. The wartime drawings were taut, scored and scratched and full of turmoil and destruction. Nash managed to depict the the devastation to the earth, the detritus of the battlefield, the explosions and the desolation of the Western Front, and by implication the effect on mankind too. The sky and clouds were always crucial to the atmosphere of his work with brooding, heavy clouds and bleak sunrises. The landscape and how it was scarred and despoiled by the war, and the dead, disfigured trees with missing branches, could be seen to represent the wounded flesh and damaged limbs of the soldiers.

In May 1918 he exhibited five oil paintings, five lithographs and a large number of drawings on brown paper, at the Leicester Galleries in London in an exhibition entitled Void of War. The paintings included The Void (which would later go to Canada as part of the Canadian War Memorial), The Mule Track, and We are Making a New World. The latter depicts a sunrise at Inverness Copse (landmarks were given English names by the troops), near Ypres, and it was bought by the Imperial War Museum.

Paul Nash and his brother John were commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee. Paul painted The Menin Road which shows the battlefield close to Ypres, while John Nash painted Over the Top which depicts the Artists Rifles at Marcoing on 30 December 1917. Both brothers worked alongside each other in a old herb-drying barn in the Chilterns. In 1919 Paul painted A Night Bombardment for the Canadian War Memorial scheme.

Nash applied again in the summer of 1918 to be an official war artist in Flanders but was turned down. He worked as a war artist during the Second World War as did Stanley Spencer.

* The apostrophe was dropped from use in 1937 as it was so often used incorrectly.

**Canadian War Memorials scheme: In 1916 Lord Beaverbrook set up the Canadian War Records Office to ensure that there was a record of the war from Canada’s point of view. Part of this was the Memorials scheme and various painters, some British and some Canadian were commissioned to produce paintings (see above). There were plans to house these works in a specially built memorial gallery but these didn’t come to fruition and the paintings became part of the collection of the National Gallery in Ottawa and in 1971 part the Canadian War Museum. Some of the paintings are displayed in the Senate chamber in Ottowa

Canadian War Memorials Painting exhibition (PDF of catalogue)

War paintings in the Senate Chamber

Related links and source material

The archival trail: Paul Nash the war artist

Canada’s war art

‘Over the Top’ and resigned to their fate. (Daily Telegraph article about John Nash’s painting)

When artists fought for Queen and country. (Daily Telegraph)

Bibliography

A History of the Artists Rifles

Brothers in arms: John and Paul Nash and the aftermath of the Great War

Paul Nash: the elements

Paul Nash: landscape and the life of objects

Paul Nash: a memorial volume

Paul Nash: the portrait of an artist

The Studio

A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War

Images sources

Library members can access the entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text. The Times Digital Archive is also available to library members.

[Fiona Campbell, Library Assistant]