Richmond Read-along 69

Welcome back to the Richmond Read-along! Today’s short story is from Herminie Templeton Kavanagh. Kavanagh was born in Hampshire to an Irish family, but lived for most of her life in the United States of America. She is best known for her stories about Darby O’Gill, published both as short stories in magazines and then as two books. These stories show the influence of her Irish heritage, featuring fairies and other aspects of Irish mythology, such as banshees, leprechauns and magicians. Her stories featured common spellings that differed from the English of most literature and give them much of their character.

Today we are reading one of her short stories that does not feature Darby O’Gill. However, the story is typical of her style in that it features a working Irish family, a small farm setting – and just a little magic.

Killbohgan and Killboggan

Once upon a time, and a black-fortuned, potato-blighted time it was, there lived near the town of Clonmel, in the beautiful County of Tipperary, a sober-minded farmer named Jerry O’Flynn.

Of cattle or horses or sheep or goats or any four-footed beasts, Jerry had none, saving and barring a beautiful white pig which he had picked up at his own threshold on a blustery evening in April, when it was a little stray, shivering, pink-nosed bonive.

Well, that same pig grew and grew, fat and silky and good-natured, till it was the pride and the pleasure of the family to currycomb him, to wash him, to feed him, and to rub his fine, broad back. And when the time came for him to go the way of all pigs, Jerry’s thatched roof covered as sore a hearted family as dwelt in all Ireland. However, the piteous law which compels the strong to prey upon the weak, was in this instance considered to be inexorable; so, the evening before the day of execution, Jerry repaired to a secluded spot behind the high, black turf stack, and there, with his own unwilling hands, arranged the grim paraphernalia for the morrow’s tragedy. When this dismal work was finished, the honest fellow had not enough courage left to carry him back to the cottage, there to face the accusing eyes of his children, so he slunk over to the stile in the lane and stood with his right arm thrown listlessly about the hedge post, lost in troubled contemplation of the unconscious and confiding victim who stretched himself luxuriously in the grass at his master’s feet.

So preoccupied was the lad with his bothersome thoughts, that he failed to notice the hasty approach of good-natured old Mrs. Clancey, and he answered her cheery “God save ye” with a half-frightened start.

“I’ve come to tell ye, Jerry agra,” the excited woman panted, “that there’s a letther—a big blue letther—from Amerikay—waitin’ for ye down in the town; and the postmasther (bad cess to him) wouldn’t let me have it to bring to you. He even rayfused to open it for me, so I might bring ye the news who it was from. The curse of the crows light on him!” She spoke with such hearty bitterness as to suggest a keenly disappointed curiosity.

“Thank ye, and thank ye agin for your throuble, Mrs. Clancey! You’re sure the letther was from Amerikay?”

“Oh, faith I am; the postmasther hilt it up, an’ more than a dozen of us saw the post mark.”

“My but that’s quare,” muttered Jerry. “I have no one in Amerikay who could be afther sending me a letther barrin’ me Uncle Dan, and Dan’s dead an’ gone. Heaven rest him, these two years. I’m bilin’ to know who the letther’s from, but I can’t go afther it the morrow becase” (and he sighed deeply) “we’ve set that day for the killin’ of Char-les, the pig, there. And it’s a red-handed murdherer I feel meself already, Mrs. Clancey, ma’am.”

Well, at these words, strange as it may seem, Charles gave a startled grunt, rose to his fat haunches, and threw a look of such resentful surprise from under his white eyelashes, first at Jerry, then at Mrs. Clancey, that the old woman, with a muttered “God save us, will ye look at that now,” shrank back a pace from the stile.

“I wouldn’t kill that pig, Jerry O’Flynn,” says she, with a warning wag of her forefinger. “I wouldn’t kill that pig if he was as full of goold suverins as the Bank of England, Ireland, and Scotland put together, so I wouldn’t!”

The smouldering trouble in Jerry’s gray eyes deepened, and he sucked hard at his empty, black pipe.

“And why wouldn’t ye, Mrs. Clancey, ma’am? What raisons have ye agin him?” asked Jerry, peering anxiously at her from under the rim of his old caubeen. Mrs. Clancey deliberately folded her arms in her shawl, and came a step nearer the stile.

“Well, first and foremost,” says she, “he is a shupernatural baste, and there’s a knowledgeableness in the cock of his white eye when he turns it on me that makes me shiver, so it does. Look at him sitting there now! Look at the saygacious twisht of the tail of him. I’ll warrant he ondherstands every worrud we’re thinking, let alone sayin’—conshurning to him.”

Jerry threw an apprehensive eye over his shoulder at the pig who now sat with his back toward them, solemnly twisting his tail first this way, then that. But for all his seeming indifference there was such a subtle suggestion of listening in the twitch of the beast’s ears and the hump of his broad shoulders, that Jerry placed a cautious hand to his mouth when he whispered: “Do ye think so, Mrs. Clancey? No, no, it’s only just the natural cultivaytion of the baste. Though I’ll not deny that Char-les has sometimes the look of a Christian on him. Then, again, his ways are so friendly and polite that it goes sore agin me heart to lift a hand till him, so it does. Sure, pigs have feelings as well as you or I, and you wouldn’t like to be kilt yourself, Mrs. Clancey, I’m thinkin’.”

The unhappy personal comparison offended Mrs. Clancey’s ever sensitive dignity so with head askew and tight lips she replied, “If I wor a pig, which Heaven forbid, I hope I’d be pillosopher enough to be satisfied with me station in life. Pigs were born to be kilt; how else could they be turned into things needful! ‘Tis the least they can expect.”

“Thrue fer ye!” apologetically sighed Jerry. “And to substantiate what ye’re sayin’, there’s the rint long due, an’ Christmas almost on top of us, and the childer needin’ shoes, an’ herself fairly perishin’ for a bit of a bonnet; an’ look at him! there sits tay, an’ bonnet, an’ shoes, an’ rint, and lashin’s an’ lavin’s of tobaccy; and here am I wid an empty poipe, too tindher-hearted to transmogrify the baste. What’ll I do at all, at all?”

“Faith, I dunno, Jerry, ma bouchal. It’s beyant me,” replied Mrs. Clancey turning to go. “But”—and a sudden thought halted her—”to-morrow is market day at Clonmel, and if that same Char-les wor my pig, I’d have him half way there before the sun stuck a leg over the mountain, and I’d sell him widout the flutther of an eyelid. By that manes ye’d shift the raysponsibility on to himself. And if Char-les is half as wise as he purtinds to be, lave him alone but he’ll take care of himself.”

With a self-satisfied toss of her head and a cheerful “Good-night,” the wise woman took herself hurriedly up the road.

Jerry leaned heavily on the stile and gazed with unseeing eyes at the brown shawl fast disappearing in the shadows, until he was startled by two short, indignant grunts at his side. Looking quickly round he met the reproachful eyes of the pig gazing steadfastly up at him.

“Arrah don’t be blaming me, Char-les, me poor lad ! Don’t look at me that way! Me heart’s fair broke, so it is. Haven’t I raised you since you were the size of that hand? an’ a sociabler, civiler mannered baste I niver saw. Musha, I wisht you were a cow, so I do; then you wouldn’t be a pig an’ have to be kilt. Heigh ho! Sorrows the day! come along up with me, agra, an’ we’ll have a petatie.”

That night, long after the hearth was swept and the childer and herself were in bed, Jerry sat with his chin in his hands gazing moodily into the smouldering turf. The heavy task of the morrow drove all wish for the bed from his mind, so the leaden-hearted lad decided to sit up until morning—the better to get an early start.

As thus he waited, the stillness of the night grew heavier and heavier around him, broken only by the spluttering of the ash-covered turf at his feet, and he felt the darkness of the room creeping up from behind, and pressing down upon his shoulders like a great cloak.

The expiring rush light on the old oak mantel above his head struggled feebly with the strangling shadows as it burned itself to the very rim of the tall brass candlestick. But the contest proved a hopeless one, and so at last with one despairing spurt of yellow flame the vanquished light sank gurgling and choking out of sight. Jerry marked how its soul in one slender, wavering spire of gray smoke crept softly upward and disappeared. With a little shivering shrug, the lad drew his stool closer into the hearth. “Some one stepped over me grave sartin that time,” he complained. “My, but isn’t this a murdherin’ shuperstitious night?”

And the turf fire at his feet—sure never before had its dull red caverns held so many weird and grotesque phantoms: an old woman with a bundle of sticks on her back glowed for an instant there, then suddenly changed and sank into a body stretched out on a low bier. And then the body rose slowly upright and stood a tall, long-faced, hunchbacked man who soon spread and spread, and then crumbled into a pack of running hounds. Jerry’s fascinated eyes watched the pack until with a sharp crackle and a little hiss of flame the hounds dropped into an open sea of gray ashes. As they disappeared a sudden chill filled the whole room, and on that instant, loud and shrill, Phelim, the old black cock, crowed from his perch outside the door—a most unlucky sign before midnight, as every one knows. Jerry flung a startled look at the clock. Its two warning-fingers pointed the hour of midnight.

He hastily drew himself together on the stool, counting the slow, heavy strokes and dreading he knew not what. The last chime of the old clock was yet tingling through the room, when Jerry heard (and his heart turned to jelly at the sound) a strange, weird voice calling from outside under the window. “Jerry ! Jerry O’Flynn!” wailed the voice, “why don’t you open the dure?”

But Jerry never moved; he sat with stiffened hair and wild, straining eyes fixed on the black window-panes.

“Jerry! Jerry!” demanded the voice, now harsh and commanding, “I ask you once more, will you open?”

Slowly, like one asleep, Jerry arose and step by step retreated backward till his groping hands touched the wall behind him. There with parted, dry lips and trembling knees he waited.

The clock had ticked five times—he timed it by his beating heart—when, without so much as a bolt being drawn, the door swung wide open, and from the blackness without what should step boldly over the threshold but Charles, the pig. Not as he was wont to come, mind you, with friendly grunt and careless swagger, but silent and stern and masterful. He marched into the room, over to the fireplace, and sat himself upright in quiet dignity upon the stool that Jerry had just left. Jerry never moved a muscle, but stood frozen with surprise and growing resentment that Char-les, the pig, should give himself so many airs and make himself so free about the house.

The beast never deigned so much as a side look at his master but, wriggling himself into a comfortable position on the stool, he opened his mouth and in a gruff, patronizing way began to speak. At the sound of the strange voice all the boy’s fears rushed back on him.

“Jerry O’Flynn,” said the pig, “what are ye afeard of? Come over and sit on that stool ferninst me, and don’t stand there shiverin’ and shakin’ like a cowardly bosthoon!”

“I’m not afeard,” quavered Jerry, as he sidled over and seated himself gingerly on the very edge of the stool. “But may I ax yez a fair, civil question?” says he.

“You may not,” snapped Charles, “you’re here now to do as you’re bid, and not to be axing questions.”

At this unheard-of impudence, Jerry’s anger got the better of his fright. “As I’m bid!” he spluttered, thumping his knee. “What do you mane? Amn’t I the masther?”

“Masther! Ho! ho! Masther! Bedad, will ye listen to that!” roared the pig. “Why, you dundher-headed Omadhuan, who has been currycombing me, an’ brushing me down all these months, an’ who has been working for me early and late in the fields to get butthermilk an’ petaties for me brakwusts, I’d like to know? Masther indeed! let me hear no more of that,” grunted the pig, crossing his legs as he spoke. Jerry scratched his head in furious bewilderment.

“Tundher an’ turf!” he gasped. “Thrue for ye, Char-les! I never thought of it that way. But thin, me lad, the raison you got such grand care was becase I intended to—” He stopped short, frightened out of his seven senses by a quiet look in the pig’s eye.

“Intended to what?” asked Charles calmly.

“Nawthin,” mumbled Jerry.

“Umph,” the pig grunted. “Fill the poipe and hand it over to me, and pay attention, for I’ve something to tell you. You know by this time, I suppose, that it’s no ord’nary baste you have ferninst ye; an’ I want ye to undherstand,” says he, pointing his pipe, “that to-morrow morning whin ye’re takin’ me to market, you’ll be thravellin’ in much betther company than I’ll be in.”

“Well, who and what are ye at all, at all?” demanded Jerry.

The pig leaned over and got a coal for his pipe. “Listen, and I’ll expatiate,” he puffed.

“You must know that I am Killbohgan, the ould ancient Milesian maygician who in an unlucky moment had the comither put on him by Killboggan, an oulder and a trifle ancienther enchanter; and who to escape from the parsecutions of Killboggan changed himself into a hare.”

“Oh, be the powers!” cried Jerry, slapping his knee with his hand. “The first hard worruk ye’ll do in the mornin’ will be to go out an’ change me flock of ducks intil a herd of cows, so it will.”

“Oh, you poor man,” sighed the magician. “There was a time when such a thrick ‘ud be only sport and May game for me. But wirrasthrue, that was hundherds of years ago. I once changed a hill of red ants into a dhrove of wild ulephants to plaze one of me sick childher. But Killboggan has dhrawn all the power from me now, an’ I used the last spell I had that midnight when I changed meself into a wee white bonive before your own horse-pittiful dure.”

The pig scratched his ear reflectively with the stem of his pipe, and smiled, and shook his head sadly when Jerry remarked:

“I always knew there was something shuperior in your charack-ther, Char-les.”

“Be that as it may be,” continued Charles, “as I was sayin’: afther I had changed meself into a hare, what did the bliggard Killboggan do but turn himself intil a hound, and for years and years he hunted me from one end of Ireland ground to the other. One day, as we were goin’ lickety splicket up the Giant’s Causeway, the villain nearly had me by the hind leg, and findin’ meself in such a dusperate amplush, I quick turned meself intil a herring and dhropped intil the say.

“Well, anyway, it wasn’t a minute till Killboggan had metamurphied himself intil a whale, and, be the mortial man, came sploshing in afther me. And so for hundherds of years we’d been rumagin’ and rampaging from one ind of the everlasting salt says to the other, till on Chewsday last April Ned Driscoll, who was out fishing for herrings, caught me in his net. And as he was passing your door that same night, I slipped out of his basket and turned meself into a purty white bonive in the road beyant.”

“Well, well, d ‘ye mind that,” exclaimed Jerry, “wondhers’ll never sayse. And you can’t gainsay, Char-les, but what you’ve got the best of good thratement.”

“It’s the truth ye’re spakin’,” nodded the pig. “And now, to prove me gratitude, I’ll show you a way to fill your pockets with goold. Whenever you need a little money, just take me to the nearest fair and sell me, for the best price you can get. Then go your ways, and never fear but I’ll be back to ye safe and sound be cock-crow.” In his excitement over this prospect, Jerry lost sight entirely of the sheer dishonesty of the plan.

“Oh, be the powers,” he exulted, “the goose that laid the goolden egg is a mere flaybite be comparison to you!”

“There’s only one thing you must be careful of,” said the magician, raising his pipe warningly to his nose, “and that one thing is this: you are on no account to sell me to a dark, long-faced man with a hump on his back, for that’ll be the tarnation schaymer of the worruld, Killboggan. But see, the day is breaking! Tie the rope to me leg, and off to Clonmel with us.”

Jerry took the sociable creature at his word, and down the road they put. But the journey was so delayed by wonderful tales of giants and of magicians and by some fine old ballads which Charles sang as they sat under a hedge to rest, that it was the middle of the forenoon before they found themselves in the busy market place of the fair. At once Jerry was hailed on all sides, and it wasn’t long till he was offered two pounds for his fine pig. Almost immediately afterwards, Red Shaun, the drover, raised the bid to two pounds ten.

“No,” cried Jerry, “I’ll not take a penny less nor three pound. And it’s ashamed I am to part with him for that. Here you, Wullum!” he called to his first cousin, William Hagen, who stood by. “There’s a letther for me in the post-office beyant; do you hold Char-les here till I go for it.”

He slipped the rope into William’s hand, and was off like a shot. It wasn’t two minutes till he was back again with the letter in his pocket. There stood William, a glad smile on his round, red face, and four gold sovereigns shining in his open palm. But the pig was nowhere to be seen.

“Where’s Char-les?” shouted Jerry, a cold fear gripping his heart.

“Char-les is gone,” chuckled William, “but here’s the price of him; and a pound more than you axed for the lazy baste.”

“Who bought him?” demanded Jerry, anxiously. “Tell me quick, who bought him?”

“Sorra do I know who the long-faced, black, ould targer was! But he seemed mighty glad to get the pig at four pounds, and was in a great hurry to be away with himself.”

Jerry tried to speak, but his voice at first failed him. “Did the schaymer have a hump on his back, I dunno?” he managed at last to gasp.

“No less,” answered William, “a hump like a camel’s. But what’s come over ye, man? You’re as white as a ghost.”

For answer Jerry pushed William aside and dashed madly into the surging crowd; and for the rest of that day he searched every nook and corner for some trace of the lost Charles; but in vain. It was well on to midnight when, footsore and sorry-hearted, the remorseful lad lifted the latch of his own cottage door. As he did, the breath almost left him, for there on the same stool, just as before, sat Charles. But not altogether the same either, for instead of the usual jolly, careless expression worn by the pig, there was now on his countenance a settled look of hopeless dejection. And Jerry noticed also that although the pig’s body was as big as ever, his sides were almost transparent. Indeed, the tongs leaning against the wall, near which the creature sat, were quite visible through the poor fellow’s ribs.

As Jerry walked slowly toward the fireplace, the pig addressed him, and the sad tremble in his voice went straight to his master’s heart.

“I’m dead now; now I’m dead, Jerry,” wailed the pig. “I wrastled with that scoundhrel Killboggan till tin minutes ago, and his spells and charrums have me melted away to a looking-glass image of meself. Oh me, oh my, oh me, oh my! Be accident I got him down at last and managed to escape and fly to you. But he’s coming. He’ll be here in a minute, and then good-by forever to the raynowned Killbohgan. I can do no more. I’ll vanish entirely.”

“Och, what a murdherin’ pity,” mourned Jerry, wringing his hands. “Is there no help for you?”

“There’s only one poor chanst in all the worruld,” moaned Charles, “but I don’t think you’d be ayquil to the task. If you could manage to stuff a handful of salt into Killboggan’s mouth, that’d put an ind to his powers and his parsecutions. I’d soon grow fat agin. But sure what’s the use of talkin’—Oh, be this and that, here he is!”

The pig made a jump and a mad scramble for the other room, and dived under the bed. and Jerry had barely time to snatch a fistful of salt from a crock on the dresser shelf, when the kitchen door flew open, and in strode a tall, humpbacked man with the longest, darkest face Jerry had ever seen.

“You have that villain Killbohgan here somewhere, and you’d betther let me have him at once,” croaked the dark man in a deep, harsh voice. He stood wide on his legs in the middle of the floor. “Ha! there he is skulkin’ undher the bed. Wait till I have him out and finish him here ferninst ye.”

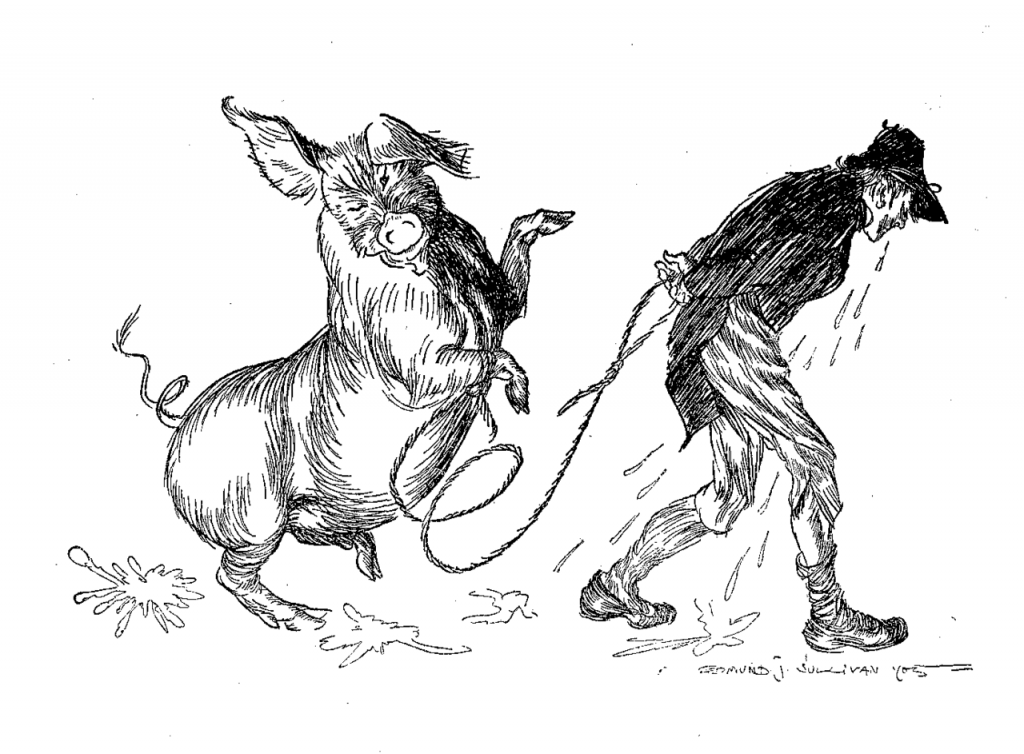

With these words the magician made a bolt for the other room but as he did, Jerry, with a courage which has since become the settled boast of all his descendants, gave a quick spring and landed fair and square on the ugly intruder’s back. And then began a struggle which for noise and destruction has never been equaled before or since in any respectable man’s kitchen. With his left arm clasped tight about the long, bony neck, Jerry strove with his right hand to thrust the fistful of salt into the villain’s mouth. Round and round spun the magician, as fast as any top, striving desperately meanwhile to avoid the handful of salt which Jerry just as desperately was endeavoring to make him swallow. From one end of the kitchen to the other they whirled, Jerry’s legs flying out behind like a couple of flails, and sweeping everything in their way. Down went the table, up in the air flew the two stools, crash went the poor old clock, and with one wild sweep the two dignified brass candlesticks flew madly off the mantel. And then, saddest of all to relate, swish! crack! went Jerry’s two legs against the churn-dasher, and the five gallons of fresh, sweet buttermilk spread like a white sheet over the floor.

“Oh, ye murdherin’ thafe of the worruld! oh me two misfortunate legs!” roared Jerry. He gave the magician such a poke in the back with his knee as to drive for an instant every whiff of breath out of the rascal’s body.

“Bravo! Bravo!” shouted Killbohgan’s smothered voice from under the bed.

At that the frantic enchanter changed his tactics. He now stood in the middle of the floor bending his body up and down with the greatest rapidity, so that Jerry fluttered back and forth like a shirt on a clothes-line in windy weather.

The brave man, however, never weakened his hold, and Killboggan soon found out that this plan was useless, too; so what does the rapscallion of an enchanter do but begin backing rapidly toward the fireplace.

“Oh, murdher in Irish, this is where the spalpeen’s got me,” groaned poor Jerry, twisting a frightened eye over his shoulder at the turf fire.

“Keep a firm grip on him whatever happens,” encouraged the invisible Killbohgan, “ye’re doin’ fine.”

Whether Killboggan intended to seat the poor lad on the live coals will never be known. At any rate, if such was his uncharitable intention the maddened wizard miscalculated the direction, and instead of finding the fireplace, he succeeded only in banging the heroic Jerry against the wall with a terrible thump.

Hard as it was on the poor lad’s bones, that same bump proved to be Jerry’s salvation; for the rattling jar of it loosened the big heavy picture of Daniel O’Connell which hung enshrined on the whitewashed wall above them, and, as though of its own volition, down came Daniel crash on Kilboggan’s head. The glass was smashed into smithereens, and the heavy frame hung itself round the neck of the bewildered magician like an oxen’s yoke.

And that wasn’t the best of it either, for at this same moment Killboggan’s two feet slipped in the buttermilk, and down he went on his back to the floor like a load of turf. The grunt the fallen wizard let out of him could have been heard in the seven corners of the parish. There was an exultant “Hooroo!” from under the bed, and the next instant Jerry, gasping and spluttering, was seated on the black lad’s chest striving still with might and main to pry open the long jaws and to crush the handful of salt through the scraggly, yellow teeth.

Slowly the great jaws opened and our hero was making haste to poke in the saving salt, when suddenly a hand caught him from behind, and a familiar voice spoke in his ear.

“Get up out of that. I’m ashamed of ye. What are ye doin’ to that stool?” It was his wife Katie who spoke.

But Jerry, breathing hard, still clung desperately to Killboggan, until looking more closely, what was his surprise and consternation to find that the Wizard had some way changed himself into one of their own three-legged stools.

Jerry rose slowly to his stiffened knees and looked about him in great bewilderment, as well he might. For now, wonder of wonders, there was no sign whatever in the room of the late desperate struggle.

From his old place on the wall Daniel O’Connell, unharmed, smiled down lofty and serene upon the neatly set kitchen, while upright and solemn the dark churn stood in its own quiet corner by the dresser. Indeed, there was not an article of furniture out of its place, and Jerry as he knelt looked round in vain for the sign of a single drop of buttermilk on the floor.

“Where’s Killboggan?” he gasped, as he struggled to his feet.

“Kill who?” laughed Katie in stitches. “I’ve seen no Killboggan or Killhoggan or Kill anybody else, aither. But you and that bliggard Char-les should be half way to Clonmel be this time.”

“Char-les, Char-les,” Jerry repeated mournfully, wagging his head, “sure Charles is gone, Katie, and we’ll never see the poor hayro again.”

“Won’t we, then,” laughed Katie. “Quit dhramin’, avourneen, and see who’s looking in the door at ye.”

Jerry looked as he was bidden, and there with his head poked over the threshold, to his master’s infinite amazement, stood Charles, fat and comfortable looking as ever, with a roguish smile in his eye which said plain as spoken words: “The top o’ the mornin’ to ye.” It was already bright daylight.

“Take ye’re bite of breakwus, darlin’,” coaxed Katie, “and the two of yez be off, but mind ye, don’t sell the pig for a penny less nor three pound.”

“Sell him ! Katie, sell him! I wouldn’t part with Char-les for any money.” At that he up and told her all that had happened during the wonderful night, and he wound up by saying:

“It may have been a dhrame, and thin agin it may have been a wision, but dhrame or wision I’ll take no chances in having the vartuous Killbohgan murdhered.”

“At laste,” insisted Katie, “Mrs. Clancey and the letther is no shupernatural wision, so take the road in your hands and bring us back worrud of it.”

And so, indeed, Jerry did, and toward evening back he came, only the top of his hat visible over the stack of bundles he carried. With dancing feet and clapping hands the children opened wide the door, and Jerry marched proudly in and began to unload. A bonnet box with a bonnet in it that eight yards of beautiful red flannel; two pounds of good black tea; three pairs of shoes for the children, “God bless thim”; and a great package of tobacco and a fine new pipe for himself.

“Me Uncle Dan in Amerikay isn’t dead afther all, Katie,” he exulted, “and to prove it he put tin pounds in the letther; and afther buyin’ all ye tould me to and lashins more, I paid the rint, thanks be, and I have still a matther of four pounds tin tucked safe an’ deep in the bottom of me breeches pocket.”

You can find this story, and others by Kavanagh, at Wikisource. Read more about Kavanagh’s life at Wikipedia.

Join us tomorrow for the next Richmond Read-along!