Artists at War: Stanley Spencer and the Second World War

In Artists at War: Paul Nash and the First World War, we looked at the role of official war artists and in particular the work of Paul Nash. In this post we look how the artists were employed during World War Two, the role of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, and the work of Stanley Spencer.

War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC)

On 29 August, just before war was declared, Sir Kenneth Clark, then the Surveyor of the King’s Pictures at Windsor and Director of the National Gallery put forward to the Ministry of Information a proposal for a scheme that was to become the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC). Clark based his idea for the scheme, and its structures and how it was run, on the war artists scheme that was initiated by Masterman, Buchan, and Beaverbrook during World War One. Clark’s aim was to create a ‘documentary and artistic heritage of the kingdom during the war through commissioning and purchasing’.

The scheme was approved on 7 Nov 1939 with the first meeting of the committee taking place on 23 November 1939. Clarke was in the chair and other members included Muirhead Bone (the first war artist appointed in 1916) and a representative of each of the armed forces. In their meetings the committee discussed exhibitions, copyright, disposal, publication and reproduction, and they also decided on possible candidates to be war artists. They would meet 197 times over the life of the committee.

By February 1940 the WAAC had drawn up a list of 247 artists – some of whom were already serving with the armed forces – who they recommended for employment under the scheme. A small number of artists (37) were employed on full-time commissions for 6 months. They were paid £325 and worked under the direction of the War Office or other government ministries and the armed services. They also received free transportation, meals and accommodation when away from home. In return they were required to submit everything they produced including sketches. The committee encouraged the development of new talent and many younger artists were part of the scheme. Paul Nash, who had been a war artist in the First World War, was attached to the Air Ministry and produced some of his most ambitious works such The Battle Of Britain. Other artists worked on commissions or had their work bought by the WAAC.

Artists and galleries saw sales of work and commissions drying up during the war and those who relied on teaching for an income found that art schools were either closed or relocated, and teaching work was hard to come by. Clark later admitted that his aim ‘which of course I did not disclose, was simply to keep artists at work on any pretext and, as far as possible, to prevent them from being killed’. He also envisioned the WAAC as way to foster a national culture and to lay the foundations for the post-war state patronage of the arts. (The Arts Council was set up in 1946 and Clark was chairman between 1955-60).

The artists produced mainly drawings, watercolours and oils, and a few sculptures and some prints. By the time scheme ended nearly 6,000 works had been created at the cost of £96,000, by more that 400 hundred artists, which chronicled Britain at war, both at home and abroad. Subjects included munition factories, the Land Army, and the conflict in all the different arenas of the war.

The works were exhibited during the war with the first exhibition being held at the National Gallery in July 1940 and proved very popular with the public. (The National Gallery was empty as its valuable works had been moved to the safety of a disused mine slate quarry in North Wales). After being shown in London the works toured around the country by freight train, being shown at various city art galleries such as Norwich, Newcastle and Aberdeen.

The WAAC was dissolved in December 1945 and a sub-committee, under the chair of Muirhead Bone, wound down the scheme while the allocations committee, under the chair of Clark, was responsible for the distribution of the work. The works were divided into those seen as works of art and those that provided a visual record of the war, with the former being deemed more important. The Tate Gallery was given priority for art, as was the British Council, with the Imperial War Museum taking both art and visual records. Works were also distributed to embassies, regiments, town halls, museums at home and across the Commonwealth.

War Pictures by British Artists

The WAAC was always looking at ways to make use of the work produced and to make it accessible to the public so, as well as exhibiting them, they were also reproduced. This included providing large printed reproduction of works for military messes, British restaurants and factory canteens. One such scheme was the publication of the eight volumes of the War Pictures by British Artists, by the Oxford University Press. These were small, affordable paperbacks and each volume had a different theme including: Blitz, air raids, war at sea, RAF, Army, women, production, and soldiers. The first four were issued in 1941 and sold 24,000 copies, with the second four volumes appearing in 1943. Artists included: Paul Nash, Edward Ardizzone, Edward Bawden, Eric Kennington and Eric Ravilious.

Recording Britain

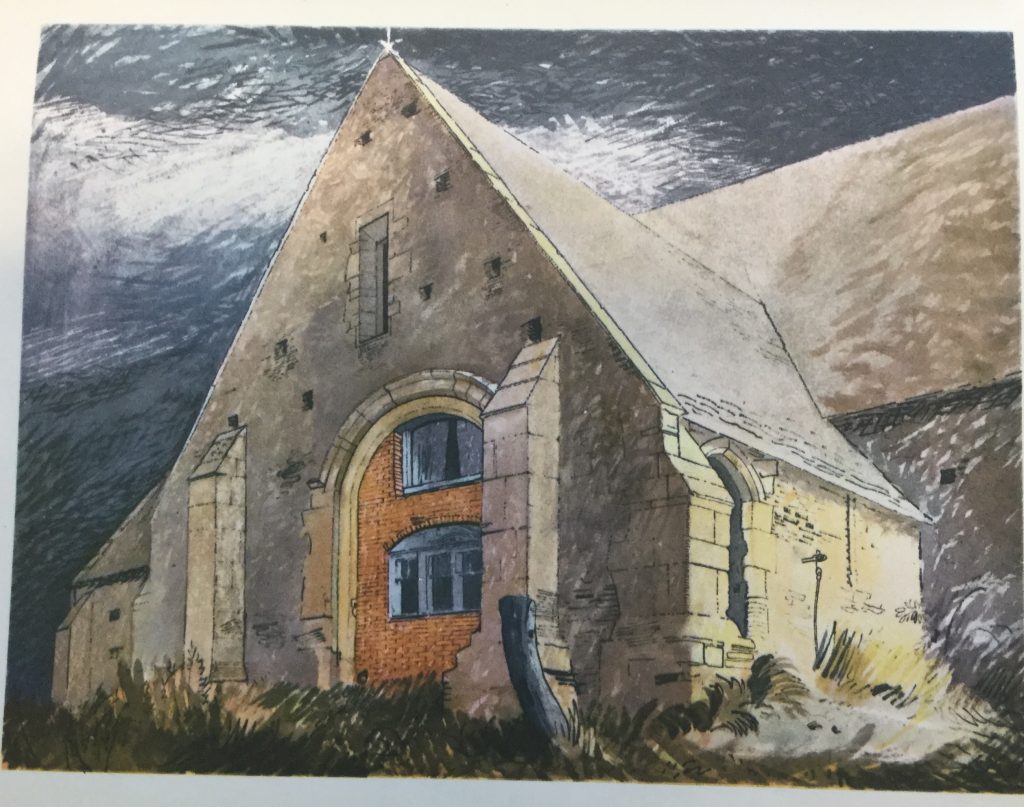

Other organisations, local authorities and businesses hired artists to record the war. The city of Sheffield appointed Richard Seddon to be the official war artist for the city and commissioned him to paint eighteen works. The Brewers’ Association employed 35 artists to record the appearance of distinctive pubs. The Recording Britain project employed artists for a period of four weeks, at a remuneration of £24 per week, for up to a maximum of 16 weeks. The aim was record Britain in watercolours and drawings. Works were arranged by county and were later published in 4 volumes in 1946. The collection recorded Britain at a pivotal moment in its history, when the British way of life may have ended for ever if the allies had been defeated or was changed by progress and development. Artists drew landscapes, buildings, rural craftsmen, agricultural workers and even an Essex tattoo parlour. The complete collection of more than 1,500 works is held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Artists included: John Piper, Enid Marx, Barbara Jones and Kenneth Rowntree. The project ran from 1939 to 1943 and was set up by The Pilgrims Trust and, like the WAAC, was the brainchild of Kenneth Clark.

Stanley Spencer

Stanley Spencer, affectionately known as Cookham because of his attachment to his home village, had served on the Macedonian front as part of a Field Ambulance Unit during the First World War, and had been an official war artist. After the war ended he was commissioned to paint works for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere in the late 1920s and he based the paintings on his wartime experiences in Macedonia and his recollections of Beaufort Hospital in Bristol and Tweseldown Camp near Aldershot. When the war was declared Spencer was 48 and was too old to be called up.

Although he was an immensely popular artist, Spencer wasn’t initially included on the list of possible artists. The intervention of his dealer, Dudley Tooth, who wrote to Clark urging him to be considered – in part because of Spencer’s financial debts owing to his falling sales – led to him being offered work. In October 1940 Spencer wrote to Tooth asking for an advance to cover the cost of winter clothes and new shoes. One of Spencer’s financial commitments was his payments to his two ex-wives.

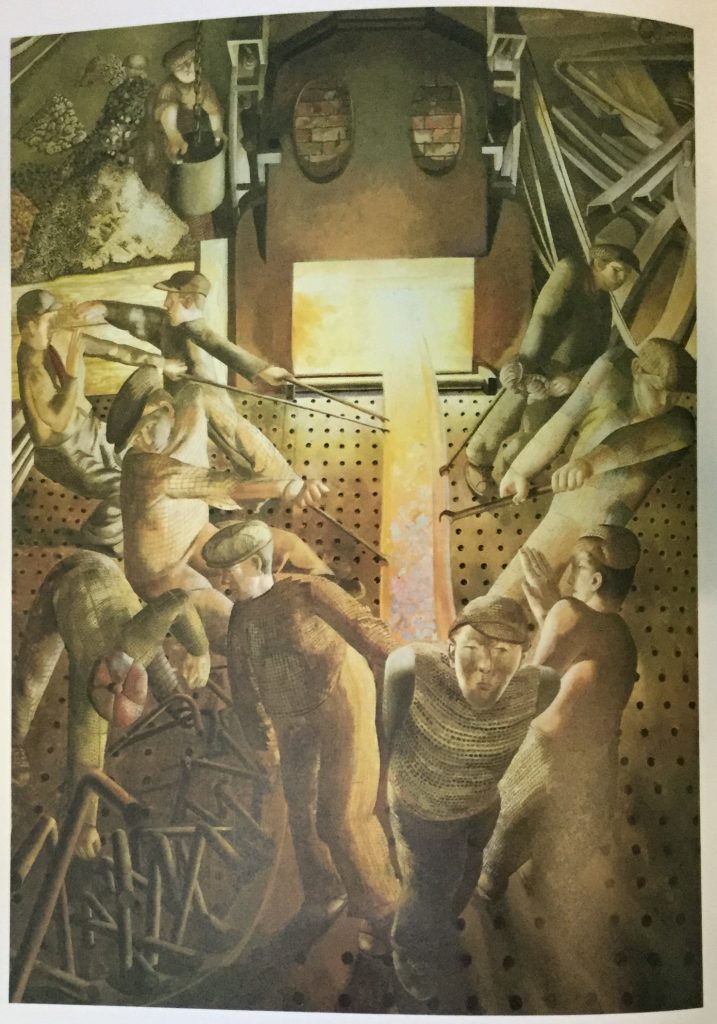

Spencer didn’t work as a full-time war artist but on short-term contacts for the Ministry of Information. Between 1940 and 1946 he worked on the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series. Originally, he drew on site at the Port Glasgow shipyard that was owned by the director of Merchant Shipping, Sir James Lithgow, where merchant ships were being built. He first visited in May 1940 and was immediately drawn to the atmosphere of homeliness and activity saying ‘people generally make a home for themselves wherever they are and whatever their work, which enables the important human element to reach into and pervade in the form of mysterious atmospheres … into the most ordinary procedures of work and place’. Spencer identified with the workers and even included several self portraits of himself in the paintings.

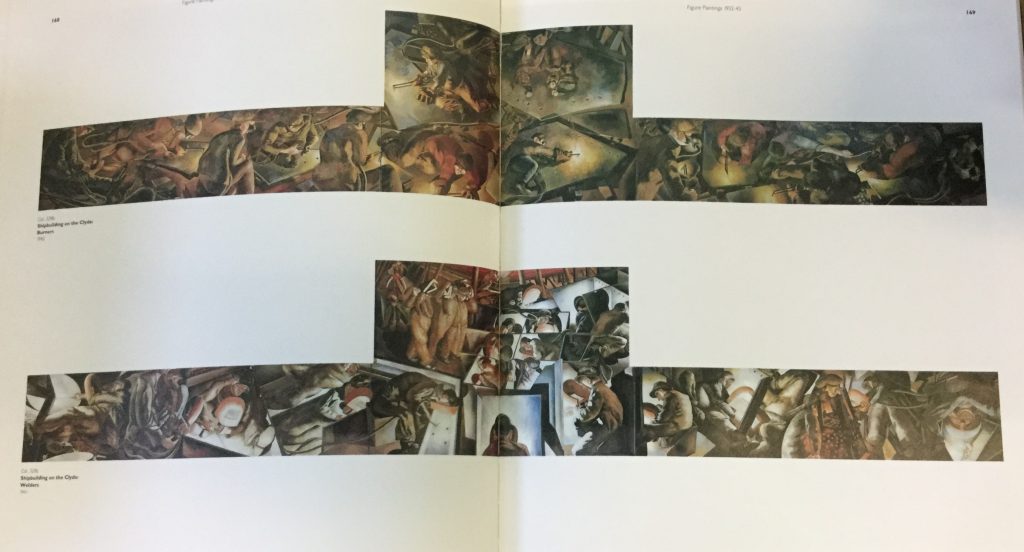

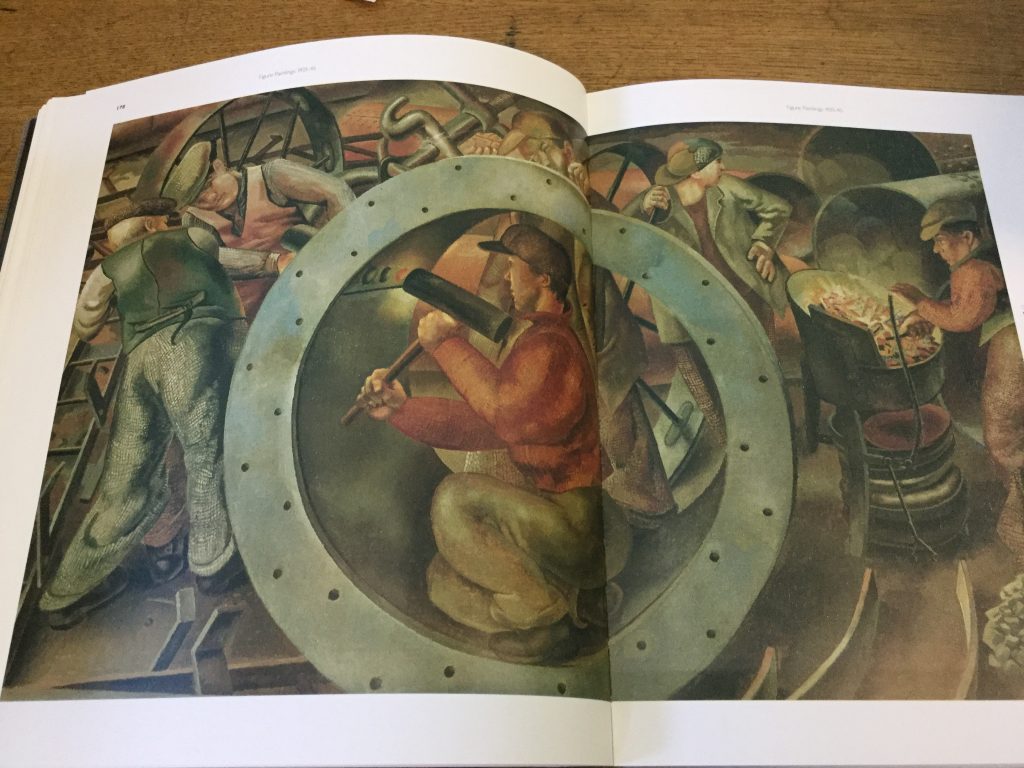

Initially, Shipbuilding on the Clyde was conceived as a frieze 70 feet in length, made up of 13 canvases, which would be hung on all four walls of a room. In the end only eight were completed: Burners, Welders, Riggers, Riveters, The Template, Bending the Keel Plate, Plumbers, and Furnaces. Spencer drew numerous quick life drawing sketches on a long roll of paper and worked these up in his studio into carefully composed drawings that were then squared and transferred to canvas,

They are extraordinary paintings because of their composition and unusual size, being very long and thin, some being composed of a central panel with longer panels on either side, rather like an elongated triptych made up of individual canvases. It was compositionally complicated, with Spencer’s use of his own slightly exaggerated perspective (especially in Riveters) with workers seen from a slightly elevated viewpoint. Everything is depicted with the same level of details and with the same handling of paint across the whole canvas. Spencer worked by squaring up his drawings onto canvas and then systematically painting from the top left hand corner of the canvas downwards.

He chose not to depict the grand launches of ships but observed in great detail the the absorption of the men in their work and the teamwork involved. Despite the scale of the ships, the sense of space in most of the paintings is small, intimate and human, and we are aware that we are seeing a fragment of the shipyard. Bending the Keel Plate is the only painting in which there is more of a sense of space,

Burners was published as a popular print by the National Gallery and the Curwen Press for the Ministry of Information while Riveters and Welders was displayed at the National Gallery in May 1941 and Shaping the Keel was exhibited there in 1943.

After the war Shipbuilding on the Clyde went to the Imperial War Museum.

Image sources

1 http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/20102

2 The Times Digital Archive

3 Recording Britain, Volume 1, page 145.

4 Stanley Spencer pages 168-9

5 Stanley Spencer page 166

6 Stanley Spencer page 179

Related links and source material

Recording Britain

Sandham Memorial Chapel

Bibliography

Recording Britain

The Sketchbook War

Stanley Spencer

Stanley Spencer: An English Vision

Stanley Spencer: The Man:Correspondence and Reminiscences

War Paint

WWII: War Pictures by British Artists

Library members can access the entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text. The Times Digital Archive is also available to library members.

[Fiona Campbell, Library Assistant]