Architectural Review: a magazine and its editors

Architectural Review (AR) was first published in 1896 and on the 120th anniversary we look at the role that its editors have had in shaping the oldest and possibly the most influential of architecture magazines.

Not all of the editors have been architects, but the majority have been; there have also been art historians, academics, writers and a poet.

Arts and Crafts

The first editor Henry Wilson was a metalwork designer, Arts and Crafts architect and a member of the Art Worker’s Guild. He resigned after the publishing company behind AR failed in 1900. He was followed by D.S MacColl who was a painter, art critic and a journalist and who went on to become Keeper of the Tate Gallery. Under his editorship the coverage of overseas architecture increased. He had various disagreements with the board which eventually led to his sacking in 1904. His successor was the architect and founder of the Art Workers’ Guild, Mervyn Macartney. Under his editorship the focus of AR began to move away from the prevailing trend of Arts and Crafts architecture and there was increased coverage of American architecture. Articles also included areas of new architectural activity such as ocean liners and coverage was widened to include furniture, decoration, garden design and sculpture as AR aimed to appeal not only to architects but also to the general public. The page size of the magazine was enlarged to accommodate the reproduction of photographs and drawings on a larger scale

Modern Movement

In 1921 the father and son Ernest and William Newton, both of whom were architects, became joint editors. Ernest died in 1922 and William continued as editor until he resigned in 1927 because of the pressure of his architectural work. Under their editorship AR began to focus on European architecture and featured many Modern Movement architects and buildings including Le Corbusier.

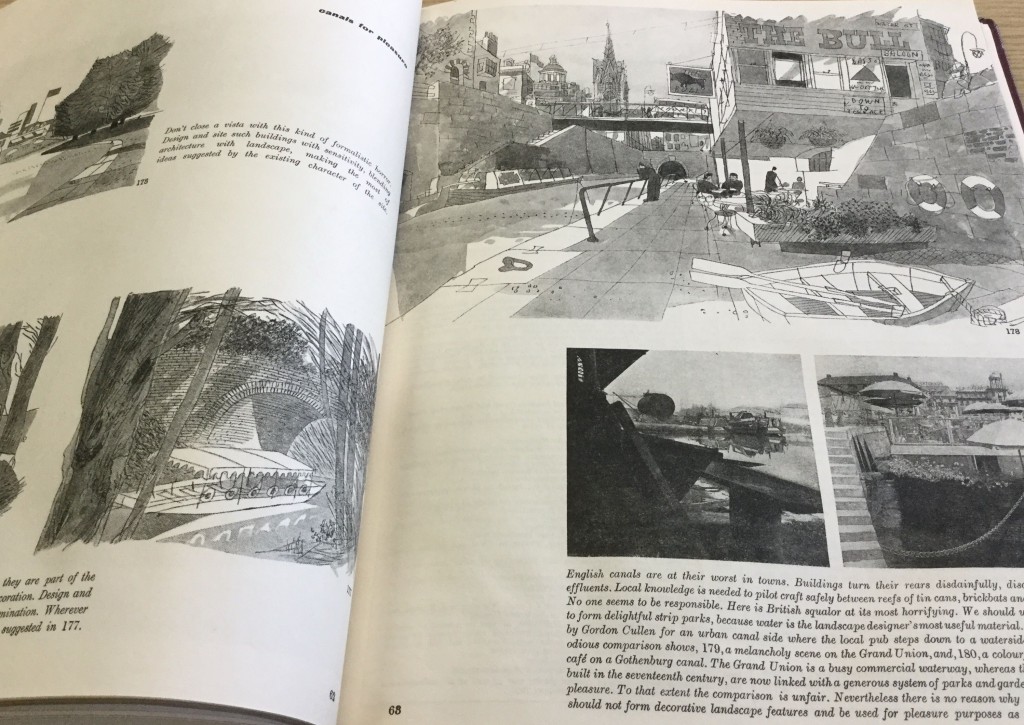

Hubert de Cronin Hastings, the son of Percy Hastings AR’s founder, was executive editor of both AR and Architect’s Journal (AJ) from the 1930s until his retirement in 1973. He studied architecture at London University but was unhappy with the ethos of the department and went to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art. As executive editor he changed the emphasis of AR so that they arts were given greater coverage and he modernised the look of the magazine and introduced new writers, such as Osbert Sitwell and Robert Byron. He was an idealist and he campaigned on various issues. For example, he used the July 1949 issue of AR to launch a national campaign to preserve the country’s then badly neglected and near derelict canals.

He rarely contributed articles to AR, and when he did they were under a pseudonym, often Ivor de Wolfe. He was a strong guiding presence behind the magazine and his irascibility often vexed the editorial board.

Betjeman

The poet, writer and broadcaster, John Betjeman had no formal architectural training but he had a keen interest in architecture and he joined the staff of AR in 1929 as Assistant Editor. His influence was immediately felt; different subjects, such as film, began to get coverage and the range of contributors became more diverse with names such as Hillaire Belloc, DH Lawrence, the painter Paul Nash, and Evelyn Waugh writing for AR. He left AR in 1935 to concentrate on producing the iconic Shell Guides.

In 1935 JM Richards succeeded Betjeman as assistant editor and in 1937, at the age of 28, he began his long and influential reign as editor which only ended in 1971 when he was 64, after a disagreement with Hastings. He began his architectural training but couldn’t complete it owing to a family financial crisis so instead he went to work in various architect’s offices but journalism provided the best outlet for his talents. Richards was an enthusiastic proponent of the Modern Movement, which was championed in AR, but he also respected and studied architecture of previous eras.

Pevsner

Nikolaus Pevsner, the academic, art historian and writer took on the role of editor of AR while Richards was on war service from 1942-1945 and he was also a regular contributor and was on the editorial board until 1965. He combined his academic life with working for Penguin on the Buildings of England series and the Architectural Press. His interest was in art, design and architecture, and he was a particular champion of the Modern Movement, and his breadth of knowledge suited AR.

There was some antipathy between Pevsner and Betjeman as they were very different characters with different approaches- Betjamin was a populist while Pevsner was more academic and learned. But by the late 1950s Betjeman and Pevsner were united by a desire to preserve Victorian buildings and in 1958 Pevsner and JM Richards founded the Victorian Society with Betjeman as the first secretary.

Loss making

In the early 1970s the magazine was losing money and direction, and its circulation was dropping and Lance Wright was handed the poisoned chalice of the editorship in 1973 until 1980. He was a architect and had been on the staff of AR since the 1960s. After the certainty of the post-war era the 1970s led to a period of self-examination by the profession, questioning its role in society. Under his editorship AR also started to question the role of the architect in society and what was the role of architecture, and to engage their readers in debate.

Peter Davey followed as editor for the next 25 years. He had studied architecture and went on to work as architectural writer and his book, Arts and Crafts Architecture, is regarded as the classic work on the subject. This was like a return to the roots of AR, when its first editor was the Arts and Crafts architect D S MacColl.

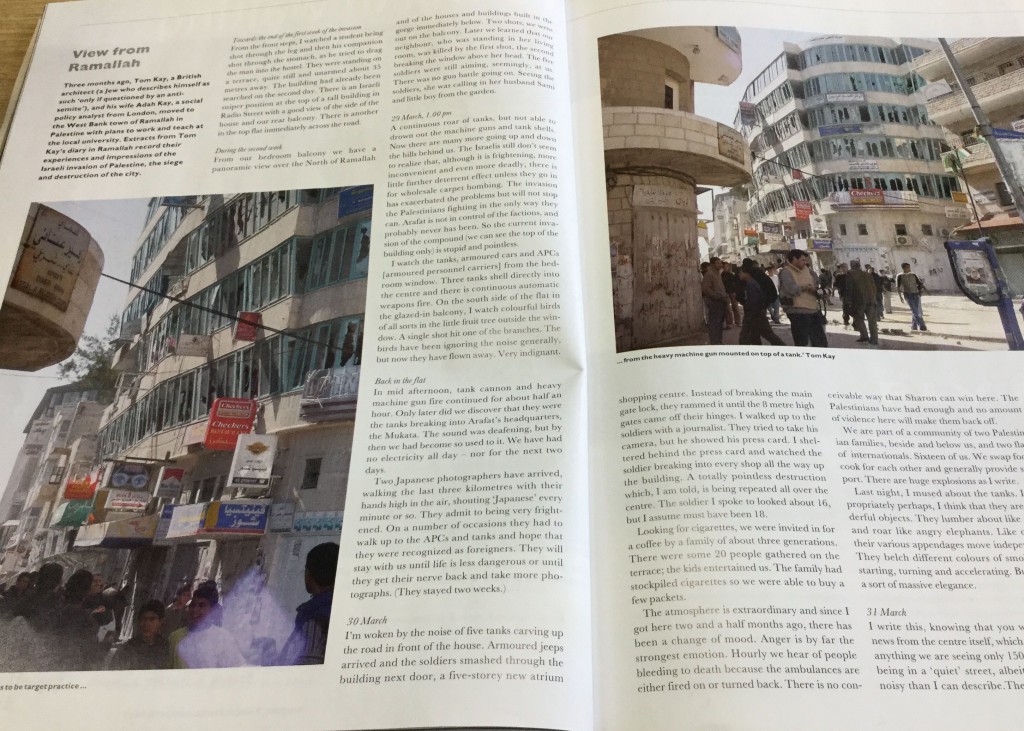

Under his editorship AR shifted away from its introspection of the 1970s and returned to championing and examining high quality, and often hi-tech, architecture from all over the world. He assembled a young and enthusiastic editorial team, including Jonathan Glancey and Dan Cruickshank, and allowed them to pursue their own enthusiasms and this resulted in a rich and varied mixture of articles and features. AR shifted towards a themed format with buildings with the same function being examined together, something that AR had done in earlier decades. There were whole issues devoted to shops and shopping centres (September 1986) and to individual buildings such as the Lloyd’s Building (October 1986). Davey believed that architecture was political as was demonstrated by the publication in May 2002 of an article called View from Ramallah, which consisted of extracts from the diary of architect Tom Kay, detailing his experiences during the invasion and subsequent siege and destruction of the city. This article provoked a huge response, both positive and negative, but Davey stuck to his belief that this was what AR should be covering.

AR begun to flourish again, with readers and advertisers returning, and he proved a worthy successor to Richards. As Hasting did before him, Davey had a couple of pseudonyms – Henry, and his sister Elizabeth Miles, that he used when not wanting to write in his role as editor.

In 2009 the architect and journalist Catherine Slessor became the first woman editor of AR. Under her editorship AR went through its first redesign for more than 20 years in April 2009. She was succeeded by Christine Murray in 2015 who was appointed with the remit of of expanding the digital coverage of AR

The Information and Reference Library takes the current issue of Architectural Review every month and has a back file from 1948.

Library members can access the entries in the online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Who’s Who for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text.

[ Fiona Campbell, Library Assistant ]