Follow the Drum: South African Military Hospital

Leading the way

Leading the way

The special collection of materials available in the Local Studies Library & Archive provides a unique insight into the ground-breaking treatments and therapies that were available to the permanently injured service men at the South African Military Hospital, Richmond Park. The South African Military Hospital was intent on modelling best practice for other military hospitals.

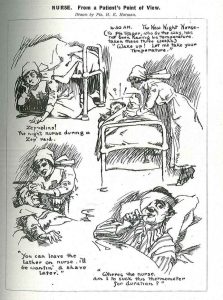

The hospital had its own magazine, named Springbok Blue to connect their South African roots to the blue uniforms worn by the patients. Available in our search room (L 362.I SOU), the two volumes cover the periods from April 1917 – March 1918 and April 1918 – March 1919. There is great wit, humour and creativity bound up in these volumes as well as lists of staff, patients, accounts of daily life and items about the hospital itself.

A clear and over-riding philosophy when it came to treating the men was the determination that every man should be able to work when they returned home. Rehabilitation of the whole person was deemed a strong priority:

‘… the re-education of the men eliminated the term “disabled” for the men who were undergoing training in these workshops were really able to do all that other men could do, and he hoped that they would all make the fullest possible use of the facilities provided’.

(Mr Otto Beit, p 91 of Springbok Blue August 1917).

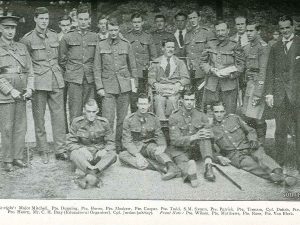

Practical aspects of re-training the men were dealt with via a selection of workshops run by the Educational Section of the hospital (the Education Organiser was Mr C. H. Bray). These included: the Electrical Workshop; the Carpentry & Woodwork Shop; Business Training and Metal Turning & Fitting. Classes were held from 10 -12 am and Instructors were also present from 2-4.00 pm (the men could attend both sessions if they wished).

Practical aspects of re-training the men were dealt with via a selection of workshops run by the Educational Section of the hospital (the Education Organiser was Mr C. H. Bray). These included: the Electrical Workshop; the Carpentry & Woodwork Shop; Business Training and Metal Turning & Fitting. Classes were held from 10 -12 am and Instructors were also present from 2-4.00 pm (the men could attend both sessions if they wished).

Otto Beit also expressed the wish that the men would all make ‘the fullest possible use of the facilities provided’. Therefore the Educational Section focused on enabling the men to gain knowledge and skills in trades that lead to a profitable career once at home. The workings of this section are regularly reported and documented throughout the ‘Springbok Blue’ magazine.

Where necessary tuition was offered regularly in Dutch for those whose first language was not English. These classes (in the Commercial section) were given by Sergeant Brink who had previously been a Master at King Edward VII School in Johannesburg. This was fundamental to creating modern business conditions to encourage the seriously wounded to plan for their future and ultimately have the opportunity to continue with their full lives.

A profile

A profile

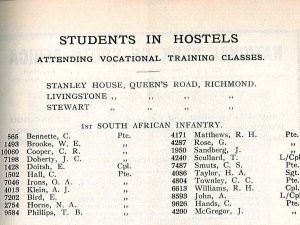

It is possible to trace the experiences of one man, Corporal Doitsh through the pages of Springbok Blue. He was part of an early exchange of prisoners and had not been able to believe his luck as few non-commissioned officers qualified for such programmes. He had been a wounded Prisoner of War at Ohrdrax in Germany, where his leg was amputated and had considered himself lucky that the operation had been conducted under anaesthetic. He had included this experience in a book he wrote about all his experiences in SW Africa, Egypt and France.

Cpl Doitsh is listed as being a member of the 1st South African Infantry and following the exchange he joined the Business Training Class at the Hospital, preparing for the London Chamber of Commerce examinations. Part of the philosophy behind these training classes was the desire to also fight a commercial war against Germany and this rationale was used to inspire the men. The range of skills covered was comprehensive: typewriting, shorthand, book-keeping and commercial correspondence.

Home from home

Home from home

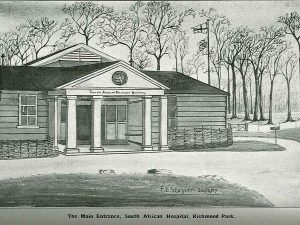

The design of the hospital is documented in Richmond Pamphlets, Volume 8 (an item featured in Building News number 3276, 17 October, 1917). This plan plus photos and sketches/drawings by the patients demonstrate how the hospital (equipped with state of the art operating theatres for its time) was planned to re-create a slice of South Africa in Richmond Park. In other words, a home from home that might provide respite for the wounded men. Even the location in Richmond Park struck a chord with homesick South African troops as the image ‘How Richmond Park might look in South Africa’ illustrates.

The style of architecture was deliberately selected to remind troops and personnel of homesteads that they had left behind (as well as being functional, practical, economical and straight-forward to construct). There is also some detail on the hospital plan that indicates arrangements for drains, water pipes and channels for draining sink and bath wastes were particularly important given the ground-breaking bath therapy offered by the hospital.

What’s in a name?

What’s in a name?

Features in the hospital and wards were named to provide close associations with home and even the hostels for those participating in workshops and training had African connections. For example, men who had completed their treatment in the hospital and were enrolled on the training courses stayed in hostels on Queens Road, Richmond that were named Stanley House, Livingstone House and Stewart House. The men could also be receiving medical treatment at the same time as vocational training.

Visitors were approved by Committee on a formal basis and social activities were a high-light of the calendar. Comforts for the wounded were an absolute priority as well. Names of the visitors to the Hostels were published in the Magazine. Every Thursday Mrs Turner of Ealing arranged socials in the evenings. It was reported in Springbok Blue that she arranged for a large number of the men to go to a matinée at Kingsway Theatre with tea afterwards. She was formally thanked for her endeavours by Sergeant Major Swan and the South African War Cry rang out through the local tea room as a sign of their appreciation.

Outcomes

Outcomes

Over time some of the patients were discharged in this country and some of them back to South Africa. Wounded soldiers were reported as achieving work placements in South Africa.

Engagements and weddings between South African men and local girls were reported in the Springbok Blue and local press from time to time. (For example, the marriage of Private J de Guelle and Miss Alicia Mary Hinks at Richmond Parish Church).

Lest we forget

The 39 men who were treated at the hospital and did not survive are buried in Richmond Cemetery. Commissioned by the South African Hospital & Comforts fund in their memory the memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (designer of the Cenotaph in Westminster). Unveiled by General Jan Smuts in 1921 it is located in an area of the cemetery known as “soldier’s corner”.

The memorial has had Grade II listed status since 2012, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has been responsible for it since the 1980s. A poignant inscription is written in both English and Dutch: Union is Our Strength / Our Glorious Dead. It is an apt remembrance of a significant time in local, national and international history.

The impact of the South African Military Hospital clearly lives on and is even reflected in some of the enquiries that are dealt with by the Local Studies Team.

Explore Your Archive

The Local Studies Team continues to develop opportunities for all to access and understand the Borough’s archive materials and is presenting a programme of workshops from 18 – 25 November 2017.

Topics covered include memorable key documents; information about how to research your house; the lives of local people directly involved in the First World War and details about how archives are maintained.

This interesting range of workshops which form part of an event called Explore Your Archive, a campaign conducted jointly by The National Archives (UK) and The Archives and Records Association (UK and Ireland), with and on behalf of the archives and records sector across the UK and Ireland.

The events are bookable by visiting your local library or by booking online at: www.richmond.gov.uk/localstudies

Tickets are £3.00 if booked in advance or £4.00 on the door. It is also possible to combine a visit to the Local Studies Library & Archive with the purchase of a ticket too. We are located on the second floor of the Old Town Hall, Whittaker Avenue, Richmond, TW9 1TP.

This blog article is taken from a presentation about rehabilitation for soldiers wounded in the First World War given by Patricia Moloney (Local Studies Assistant) in conjunction with The National Archive (Richmond Park’s South African Military Hospital, 13 September 2017 at The National Archive). The article is based on the main points covered and the key images used to illustrate what life was like for the men as they recovered from life-changing injuries.

Bibliography

Maps

- Richmond Park 1916 VTC Cycle Section LM 0898 R

- VTC on card & partially shaded LM 0481

Images

- Photos/postcards x 3 LCF 14495; 14496

- A selection of images in the magazines ‘Springbok Blue’ & ‘Richmond Pamphlets’

- Helen Bain Album DC 2/1/1

Reference Material

- Letter from Borough librarian to editor of Surrey Comet

- Photocopy of Appendix III, The Medical Services by John Buchan The History of the South African Forces in France

Journals/magazines

- Springbok Magazine 1 (April 1917 – March 1918) L 362.I SOU

- Springbok Magazine 2 (April 1918 – March 1919) L 362.I SOU

- Richmond Pamphlets (Building News No 3276, October 17th 1917) L 040

For additional material read the companion article Follow the Drum: The South African Presence published in this blog in April 2016.

[Patricia Moloney, Local Studies Assistant]