History On My Doorstep, Part 1

Welcome to the second of the guest pieces by Di Murrell in celebration of Know Your Place Festival 2021. In the first part of this piece, Di discovers some intriguing lettering that starts her on a journey back to the late 1800s.

History is everywhere and to be found on all our doorsteps, though arguably, it often lies more weightily upon some than on others.

My doorstep in west London is positively loaded down with what I think of as both ‘big’ and ‘little’ history. Take Hampton Court Palace, for instance, which is very close to where I live. I know as much as the next man about the Tudors: Wolsey, Cromwell, Henry and his wives – all of which is fascinating stuff. But who knew these fine people would happily eat dormice for their dinner during the winter-time; dormice raised and fattened and then left to hibernate in small nets hung in a cool part of the kitchen quarters. When the royal appetite fancied a roasted dormouse what better than to have a ready supply to hand; the snoring beasts could be humanely dispatched with a quick bash on the head, speedily prepared and served up as tasty morsels for the king and his company.

So for me, Tudors are ‘big’ history and dormice are ‘little’; and who knows what unrecorded influence the ‘little’ may have had upon the ‘big’? Might the Church of Rome still be our dominant religion and Anne Boleyn peacefully dead in her bed had Henry not been feeling liverish on the days in question; suffering some internal trauma, perhaps, brought on from eating too many dormice, too quickly, the night before?

I definitely have a preference for the ‘little’ history side of things.

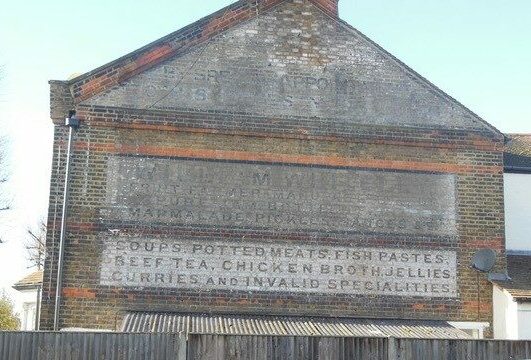

My point is that these ‘little’ historical nuggets of peculiar interest are all around us; it’s simply a matter of spotting them. It was, for instance, sheer chance that I should see some almost obliterated lettering on the side of a building recently that caused me to set off, nose to the ground, like a truffle hound. Had I not been walking to the local Home Base DIY store (somewhere I rarely visit and never before on foot, it being located in a particularly barren hinterland hard by the Great Chertsey Arterial Road) I would not have seen the old advertisement painted onto the side of an end-of-terrace late 19th century house. Perhaps it was the time of day and the way the light caught it but though I have driven past this particular spot many times, I had never noticed it before. The words were painted directly onto the brickwork and over the years had become almost illegible. I took some photos and spent a good while pouring over them trying to decipher the weathered script. Once understood they seemed such a prosaic set of words yet every line contains the ‘little’ history of lives past and former ways.

It said:

By Special Appointment

To His Majesty Edward VII

William Whiteley

Fruit Farmer, Manufacturer of

Pure Jam, Bottled Produce,

Marmalades, Pickles, Sauces etc.

Soups, Potted Meats, Fish Pastes,

Beef Tea, Chicken Broth, Jellies,

Curries and Invalid Specialities

Like most people, I have often seen that ‘By Special Appointment’ sign on various items and sort of knew it meant the Queen bought them, giving this, her seal of approval, a kind of regal ‘thumbs up’, but had never really paid it much mind. Now I discover that since the Middle Ages tradesmen who have acted as suppliers of goods and services to the Sovereign have received the Royal Warrant by way of recognition. In the beginning, this patronage took the form of royal charters which were given to various trade and craft guilds – these later became known as livery companies. Henry II granted the earliest recorded Royal Charter to the Weavers’ Company in 1155. In 1394 Dick Whittington was instrumental in obtaining a Royal Charter for his own Company, the Mercers, who traded in luxury fabrics. By the 15th century it was the royal tradesmen, rather than the livery companies, who were recognised by a Royal Warrant of Appointment. One such recipient was William Caxton, the first English printer, who, after setting up his press at Westminster, became the King’s printer in 1476.

A Thomas Hewytt was appointed to ‘Serve the Court with Swannes and Cranes and all kinds of Wildfoule’ in the reign of Henry VIII and a hard-working Anne Harris was made the ‘King’s Laundresse’. Elizabeth I’s household book listed, among other things, the Yeomen Purveyors of ‘Veales, Beeves & Muttons; Sea & Freshwater Fish’. In 1684 goods and services to the palace included a Haberdasher of Hats, a Watchmaker in Reversion, an Operator for the Teeth and a Goffe-Club Maker. According to the Royal Kalendar of 1789, a Pin Maker, a Mole Taker, a Card Maker and a Rat Catcher are among other tradesmen appointed to the court. In 1776 a Mr Savage Bear was ‘Purveyor of Greens Fruits and Garden Things’, and in 1820 a Mr William Giblet was supplying meat to the table of George IV.

Who knew?

It was with Queen Victoria, apparently, that Royal Warrants really took off and gained the prestige they enjoy today. During her 64 year reign the Queen and her family were responsible for granting some two thousand.

The next line of the advertisement bore the name – William Whiteley. I discover that he became a recipient in 1896 and, even after Victoria’s death in 1901, had continued to hold the Royal Warrant supplying goods to her successor, Edward VII.

William Whiteley?

The name rang a bell; a vague memory stirred; something I once knew.

Oh yes! Wasn’t he murdered?

He was, but for this amateur food sleuth it was his impact as a Victorian businessman and as the purveyor of items such as those advertised on the wall of that house on the outskirts of Twickenham that engages my attention. His murder simply brought him to an abrupt termination and is of little consequence here.

Sorry William!

William Whiteley was already financially successful when in 1891 he purchased a quantity of rich farmland in the rural environs of Hanworth, Middlesex. No farmer though, William was actually a hugely successful shop-keeper. Whiteley’s Department Store, by then long established in Bayswater, was the largest and most famous shop in London: the Harrods of the 19th century and a household name. When Eliza Doolittle is sent “to Whiteley’s to be attired” in George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Pygmalion’, the reference would have been a perfectly common-place allusion, immediately recognised and understood by the audience.

Whiteley, a draper’s assistant from Yorkshire, had arrived in London in 1863 with just a few pounds in his pocket. Forty years on, his stores, farms and factories, employed some 6,000 people. Although it was the newly emergent middle classes who were the core clientele of William’s famous store, aristocrats and royalty, both British and from abroad, shopped there too. Famously the shop offered and delivered – ‘Everything from a Pin to an Elephant’. Customers were, however, in the main, successful tradesmen, merchants, manufacturers, attorneys, shopkeepers, owners and developers of property, their wives and families. Many, like William, were entrepreneurs engaged in what might be termed the first consumer revolution. These were the people who enjoyed the genteel pleasures of display and emulation; the class that could afford to partake of William Whiteley’s potted meats, fish pastes and beef tea.

He was a truly self-made man and typical of the period in which he lived. An energetic driving force, not a little ruthless when he needed to be, and here he was, slap bang on point, witness to, and, indeed, part of the rapid rise of an ambitious group of people who we have come to call ‘the middle classes’. Their aspirations were surely reflected in the development of the department store; less exclusive, more egalitarian, places where anyone might go to shop. Indeed it has been said that being ‘middle class’ was not so much an income bracket, rather, it was an idea. To wander through a department store even when one could not quite afford to buy could awaken a desire for what might be: to subscribe to the idea of an entrepreneurial society; to become part of the reorganisation of wealth in Britain.

Suffice, then, to say, that given a rapidly expanding customer base and with premises in place, all that was required was for William to provide for their needs and desires, and at the same time, expand his own business interests and his penchant for ‘empire building’.

As the Enclosure Acts drove more and more people from the land, the very poorest were forced into towns that could be deeply unpleasant places in which to live; cramped, squalid and insanitary: conditions that created breeding grounds for diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis. What quickly became clear was that if such people were to be employable they had to be properly housed and fed and their overall situation improved. They needed to be healthy and motivated. Thus in an era before the introduction of the welfare state a form of caring paternalism for the ‘lower classes’ took hold. Though largely motivated by a sense of civic duty, it was also based on the realisation that for new business enterprises to be successful the work force needed to be grown and nurtured. And, more prosaically, though hard today to imagine, this was still a world where the vast majority had no personal means of transport and must mostly walk everywhere. Even with the invention of the ‘safety bicycle’ in 1885, it would still be some years before the bike became commonly used by working people. In order to toil for the long hours then expected, particularly in the horticultural industry, people needed to live close to where they worked.

Industrialists began to build their factories in rural locations. They provided decent housing for workers, often better than anything ever dreamed of by the occupants, and more crucially, close to the workplace. These were, notably, men like George Cadbury who built the village of Bournville; William Lever’s Port Sunlight where more than 800 beautiful Arts and Craft houses, a hospital, schools, an open-air swimming pool, allotments, church and temperance hotel were created; Titus Salt’s houses and works at Saltaire; the Wedgwoods who moved their factory out of Stoke-on-Trent into the nearby countryside, building charming houses for their workforce; and Joseph Rowntree who provided similar housing for his workers. Capitalism was, at that time, vested in the individual – it was personal. When young men could turn themselves from penniless shop assistants into property owners and manufacturers, their accumulated wealth was private rather than corporate. They could, if they wished, ensure that the economic benefit of their enterprises was felt locally and could be put to humane purposes. The fact is, however, that for some, philanthropy went hand-in-hand with a hard-nosed business acumen. William Whiteley being just such a one.

Written by Di Murrell.

Come back next week to see what else Di’s investigations uncovered.

Image provided by the author.

Very,very interesting , I learned a lot. Looking forward to next week’s story.