Custard Tarts – Their Chequered Past, part 1

The town of Richmond-upon-Thames has long been associated with pleasure, with prosperity, as a pleasure ground of the gentry, the rich and the famous. Plenty of signs of wealth up on Richmond Hill and beyond, yet strangely no great mansion or palace is to be found along its waterfront. Surely here one would expect to find another of the pearls in that necklace of aristocratic homes and royal residences strung out along the banks of the river hereabouts: Marble Hill House, Ham House, Syon House, and Hampton Court Palace – Arcadian dwellings all, whose occupants once relied upon the river highway to provide the easiest and quickest route to and from the city of London. It was the artery along which everyone once travelled. There should be a royal palace here.

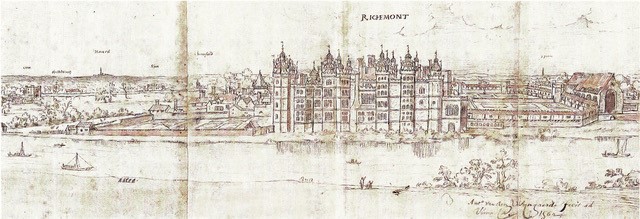

In truth, there has indeed been an august residence close to Richmond riverside, from the earliest of times, known and described in various documents for some 900 years. Today the remnants of this lost palace are hidden in plain sight, and for somewhere that no longer exists history records many notable and memorable events that once occurred within its walls. Richmond Palace was the unluckiest of places, the most under-appreciated, unrecognised and ignored palace in English history, where a series of unfortunate events led to its downfall and eventual demise. Despite all that took place there, today one must search hard for the few clues that show where the palace once stood.

First noted in the Domesday Book as the Manor of Shene (later known as Sheen), in 1125 a substantial building on the site was listed as part of the royal manor of Kingston. Later, during the reign of Richard II, the manor was enlarged and embellished, its perimeter reinforced, and turned into a royal residence then known as the Palace of Sheen. Richard was the earliest monarch to live in the palace and it was here, in 1394, that his first wife, Anne of Bohemia, died from the plague. Such was his grief that he had the palace totally demolished and its resources spread around the country. Thirty years later it was resurrected by Henry V but funds for its improvements were constantly diverted to fight his wars with France. More work was undertaken in 1445. Later Edward IV gifted it to his wife who lived there until 1487 when it was taken from her by Henry VII. Henry spent huge amounts of money on its improvement but while work was still ongoing in 1497 a fire broke out and once again it was completely destroyed. In 1501 the palace beside the river, some nine miles upstream from the Palace of Westminster, was finally completed and formally renamed in honour of his, Henry’s family, henceforth to be called the Palace of Richmond; soon after the surrounding area also became known as Richmond. Then in 1507 part of the building collapsed nearly killing the young prince Henry. Whether this was the reason that as king, Henry VIII had little love for Richmond Palace, it is well known that he much preferred life at Hampton Court, though perhaps significantly for our story, it was Richmond that became home to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and their daughter Mary. Indeed, both of his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, loved the palace and Elizabeth was later to die there. Sadly, few of her successors cared to live at Richmond, and the palace became little more than the royal nursery. Finally, and most tragically, after the execution of Charles I, sometime during his three-year rule as Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell stripped the palace of its worth, even down to its very stones, and sold off all for profit, thus destroying another symbol of the monarchy that he and his followers had come to hate.

By the early 18th century most the land, having reverted to the crown, was leased off and built upon and the few structures of the palace that survived – the stables, the wardrobe, the gatehouse – were restored. It also appears that four houses were built on the site of the palace just beside the entrance gate. The houses were a speculative development, built by a carpenter, whose name, confusingly and perhaps no more than coincidentally, was Thomas Honour. They were occupied by 1719. Two of them were rented by the then Prince of Wales (the future George II) for his wife’s maids of honour. The houses became known as Maids of Honour Row. The maids were recorded as paying rates and continued to be charged until 1737. They occupied the two middle houses. The maids received a stipend of £200 per year in addition to their board and lodgings in these houses. It does seem fairly likely that the houses were so named for their first occupants but it is just possible that builder, Thomas Honour, may have had daughters of his own and the houses so-called for them.

My story is of a sweet confection known as the Richmond Maids of Honour tart. These tarts, supposedly still made to the original recipe, have a creamy curd cheese centre set in a light puff pastry casing. Their initial association with Richmond itself may be, on closer examination, a little tenuous, nevertheless the most popular version of their claim to celebrity is set in the palace at Richmond and is, therefore, a rare reference to its earlier existence. The story goes that Henry, during a visit to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, who was living at the palace at the time, found her maids of honour eating sweet curd tarts from a silver dish and upon tasting one himself was so taken that he named them Maids of Honour and ordered that they should, henceforth, be for royal consumption only. The recipe was then, apparently, locked away in an iron box at the palace, the unfortunate maid who had invented them imprisoned within the palace grounds and ordered to produce the little confections on demand for Henry and his Royal Household alone.

Anne Boleyn was herself a maid of honour; one of the young ladies there engaged to entertain the queen and look after her needs. The queen was Catherine of Aragon, she whom Henry became so desperate to rid himself of when she failed to produce a male heir to the throne. Catherine spent much of her time at Richmond Palace – preferring it to Henry’s choice of Hampton Court. Thus far then one imagines there is truth in the visits made by Henry to see his wife and daughter and that the young Anne Boleyn, who had arrived at the court in 1522 and become part of his queen’s entourage, had caught his eye. Further, given that at least three of his future wives were maids of honour at various times it seems likely that he frequently enjoyed checking over whichever was the current team of young ladies and even indulged in a little flirtatious behaviour. The story of the tarts seems to fit.

Another version, with less traction, suggests that the tarts were first made in the kitchens of Hampton Court Palace and Henry VIII on discovering the secret recipe that had been locked away, presented it to Anne Boleyn. It was she who then made the tarts for the King when he fancied one and he, in turn, named them the ‘Maids of Honour’ for her. It seems unlikely though, that a young companion to the queen would ever have ventured into the hell-hole that was a royal kitchen. On the other hand, it is conceivable that such small and dainty tarts might have been made by some skilled pastry cook employed there.

Except that one might reasonably expect some independent comment concerning the existence of such illustrious little pastries to have emerged. There appears to be no traceable source regarding Henry’s actual encounter with them nor any independent contemporary account either. No further mention of these very special tarts and their royal association is to be found. One can only speculate on the origins of this story and when it first arose.

Tracing the history and real provenance of these little tarts has become something of a quest for this amateur food sleuth. After all, we are really only discussing the origins of a name, being unable to prove forensically that the tarts we now call, ‘Maids of Honour’ and buy today, bear any relationship to ones possibly baked in Tudor times. However, English medieval cookery sources do indicate a huge variety of custard, cheesecake and almond tarts, and the filling of many of them is quite similar to today’s Maids of Honour. The rare and expensive ingredients such as sugar, cinnamon, saffron and rosewater, though unlikely to be found in any average household of the period, would have been easily available to a royal kitchen. The charcoal fired ovens in the palace kitchens of the time were perfectly capable of baking pastry under the eye of a vigilant cook. An early version of ‘puff’ pastry, where layers of pastry are interlaced with butter and then rolled out, and most closely related of that used for the casing of the Maids of Honour tart, was first recorded in England by Gervase Markham in 1615, in his book, The English Housewife; an indication that the recipe had long been in circulation prior to that time. On the other hand, it does seem that while there were many recorded recipes in existence for different forms of custard filled tarts none featured both a puff pastry shell and a curd cheese filling. The closest recipe to our little tart appears in the second edition (1665) of The Accomplisht Cook by R. May.

We cannot know if the Maids of Honour tart of today is anything like that which may have existed in Tudor times. What is odd though, is that the current version that one can today enjoy in a teashop at Kew, and supposedly made to the original recipe, bears a remarkable similarity to a much more famous Portuguese tart known as Pastéis de Nata. Its pastry case is layered, is light and puffy, and the filling is a type of custard. So similar are they in both looks and taste that comparison is inevitable; investigation into the possibility of a relationship between the two beckons. One wonders, if there are any seeds of truth at all in the original story, might there have been some Portuguese connection to the court of Henry VIII; perhaps a continental pastry cook working in the royal kitchen, one of Queen Catherine’s retinue? England and Portugal had enjoyed a close relationship for centuries prior to Henry’s reign. Alliances by marriage were usual and the courts of the two countries intermingled. Although Catherine of Aragon was herself Spanish rather than Portuguese, is it too far-fetched to assume that there was some overlap between the cuisines of both countries? A series of marriages during the 1500s between Portuguese and Spanish dynasties may well have led to an intermixing of the dishes produced in the royal kitchens. Relevant too, is that by 1500 the trade in spices and other goods was well established by the Portuguese; an important factor given that our little tart contains ingredients such as nutmeg, cinnamon, saffron and rosewater. Such confections then would have been the prerequisite of the rich. The cost of sugar alone and the novel spices brought back from the New World would have put such delicacies beyond the grasp, and pockets, of any but the nobility. To cook such things required ovens whose temperature could be controlled and a skilled kitchen staff to attend to the careful mixing, making and cooking of same. Catherine came from just such a background and when she came to England there would surely have been at least one pastry cook in her entourage.

Given her origins, Catherine may have eaten something similar to these little Portuguese tarts in her native country. The origin of puff pastry appears to be Spanish, with traces of earlier Arab or Moorish influences. It may be a descendant of filo dough which was first used by Arab and Turkish cooks. Translations from the Arabic show puff pastry to have been made in Moorish Spain in the 13th century when there was an ‘obsessive interest in the topic of altering pastry’. The first known recipe for a modern type of puff pastry (layering it with butter or lard) appears in the Spanish recipe book Libro del arte de cozina (‘Book on the art of cooking’), written by Domingo Hernández de Maceras published in 1607 and, as already mentioned, a version of European puff pastry is found in The English Housewife (1615) by Gervase Markham. Here the dough is neither folded nor rolled up, but several sheets of dough are stacked with butter between them and then rolled out.

Nevertheless, a recipe published in England some 100 years after the tarts that might have first been enjoyed at Richmond Palace does not preclude the possibility that the knowledge of how to make them occurred long before their appearance in a book and becoming public knowledge. Might not one of Catherine’s own staff have made them for her? A comforting reminder perhaps of happier times before she was beset with the travails of her marriage to Henry.

Taking speculation even further: is it possible that a royal connection with the tart did exist, but with another person entirely? Could the Henry story be but a garbled version of one more likely though less colourful? In 1662 the Marriage Treaty between the Portuguese and English royal families gave another Catherine – Catherine of Braganza – daughter of King John IV of Portugal, in marriage to Charles II of Great Britain and Ireland. Her dowry included Tangiers and Bombay as well as free trade to Portuguese colonies in Brazil and Asia. In return Charles raised a brigade of troops to serve in Portugal’s Restoration War against Spain. This Catherine does seem to have had some interest in culinary matters: she is credited with popularising tea-drinking in England, something now regarded as part of the British culture; she had oranges regularly shipped from Portugal and introduced the court to the sweet orange jam known as ‘marmelada’; she championed the use of the fork for everyday eating.

Throughout that century there was a growing fascination in England for food from mainland Europe. Fuelled by political events, such as the marriage of Charles I to the French princess Henrietta Maria in 1625, the forced exile in France and Holland of many supporters of the royalist cause during the Commonwealth, and Charles II’s marriage to the Princess Catherine in 1662, foreign food was all the rage. Might not one of these new-fangled foreign conceits making its appearance on the English table have been a crisply flaked pastry tart filled with a creamy custard?

It is not known whether Catherine spent much time at Richmond where, after the depredations of Oliver Cromwell, little now remained. What is known though is that in 1662 on 29 May, Charles and his bride arrived at Hampton Court where they stayed for over a month and later, in 1665, they again spent some months there, having fled from London to escape the plague. Though their time in residence on both occasions was relatively short, it still allowed plenty of time for the tarts to have been introduced and baked in the royal kitchens, perhaps to accompany the green tea so favoured by Catherine and commanded to appear at around five o’clock each day.

Written by Di Murrell.

To be continued… check back next week to find out what else Di uncovered about these tarts, as well as recipes to make your own at home.

All images provided by the author.

Leave a Reply