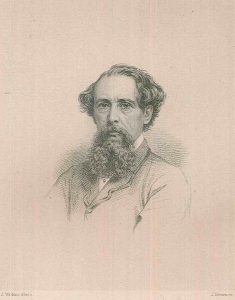

Charles Dickens and Richmond – [Local History Notes: 20]

Estella in Great Expectations (1861) states:

‘Our lesson is that there are two Richmonds, one in Surrey and one in Yorkshire, and that mine is the Surrey Richmond.’

As early as August 1836 – during the period when The Pickwick Papers was being published in monthly instalments – we find him on holiday in Petersham. His letters are headed simply ‘Mrs. Denman’s, Petersham, near Richmond’. He may well have been staying at the Dysart Arms where the proprietor at that time was a John Denman.

A letter written in October 1837 to his friend and biographer John Forster, inviting him to participate in a pleasure trip, suggests that Dickens was already familiar with other parts of the borough: ‘I think Richmond and Twickenham through the Park, out at Knightsbridge, and over Barnes Common, would make a beautiful ride.’

Readers of The Pickwick Papers will remember that, in the final chapter, Tracey Tupman retires to Richmond:

‘…where he ever since resided. He walks constantly on The Terrace during the summer months, with a youthful and jaunty air which has rendered him the admiration of the numerous elderly ladies of single condition, who reside in the vicinity.’

During the first half of the 19th century, the Star and Garter Hotel on Richmond Hill gained an enviable reputation under the management of Joseph Ellis. Dickens and his wife stayed there towards the end of March 1838. The purpose of this particular visit – apart from that of aiding his wife’s convalescence – was to be out of London on the day that the first number of Nicholas Nickleby was published, for – as Forster writes in his biography: ‘Having been away from town when Pickwick’s first number came out, he made it a superstition to be absent at many future similar times.’

On this occasion, Forster spent a Sunday with Dickens at Richmond to celebrate their respective birthdays and also Dickens’ wedding anniversary. This celebration apparently became a tradition over a period of twenty years (except when Dickens and his wife were out of England) and it always took place at the Star and Garter. The Hotel was, indeed, a favourite resort of the author, whether as a place to meet friends and to celebrate a particular event o, or as simply a haven where he could recuperate after many strenuous weeks of work. Early in 1844, a dinner party took place there to celebrate the birth of the novelist’s third son. But perhaps the most important Dickens gatering at the Star and Garter was that of June 1850 when Thackeray and Tennyson were among the guests celebrating the publication of David Copperfield.

Returning once more to the year 1838, we find Dickens and his family spending the summer in Twickenham – at 4, Ailsa Park Villas (near the present St. Margarets station), which he rented during June and July. In a letter to Forster of May 1838, he wrote: ‘Kate is going in a fly to Twickenham to look at the cottage and we are to join her there.’

Dickens was now working on Oliver Twist, but he found time to entertain many visitors at Twickenham and also to form a balloon club for the amusement of his children. The club was called ‘The Gammon Aeronautical Balloon Association for the encouragement of Science and the Consumption of Spirits of Wine’. Forster was elected president with the duty of supplying the balloons.

In the spring of the following year Dickens became re-acquainted with Petersham. His diary entry for Tuesday 30th April 1839 reads: ‘Took possession of Elm Cottage, Petersham [in the Petersham Road] for 4 months – Rent for term: £100.’

The outdoor recreations here, as described by Forster, were rather more strenuous than those at Twickenham:

‘Extensive garden-grounds admitted much athletic competition, from the more difficult forms of which I in general modestly retired, but where Dickens for the most part held his own against even such accomplished athletes as MacLise [Daniel MacLise, the artist] and Mr Beard [Thomas Beard, a journalist friend]. Bar-leaping, bowling and quoits were among the games carried on with the

greatest ardour; and in sustained energy, what is called keeping it up, Dickens certainly distancing every competitor. Even the lighter recreations of battledore and bagatelle were pursued with relentless activity; and at such and which he visited daily while the amusements as the Petersham races, in those days rather celebrated, and which he visited daily while they lasted, he worked much harder himself than the running horses did.’

From Petersham it was not far to Hampton and Dickens also visited the race meeting held there in June. It cannot be mere coincidence that in the July number of Nickleby, Sir Mulberry Hawk and Lord Frederick also visited the Hampton races:

‘The little racecourse at Hampton was in the full tide and height of its gaiety; the sun high in the cloudless sky. Every gaudy colour that fluttered in the air from carriage seat and garish tent-top shone out in its gaudiest hues.’

The subsequent quarrel between the two men on the way back from the races led to the duel which took place in Petersham:-

‘Shall we join the company in the avenue of trees which leads from Petersham to Ham House and settle the exact spot when we are there?……they at length turned to the right, and, taking a track across a little meadow, passed Ham House and came into some fields beyond. In one of these they stopped.’

In a more sinister connection, Hampton had also featured briefly in Oliver Twist. It is there that Bill Sikes and Oliver halt for a while at ‘an old public-house with a defaced sign-board’ on their way to the burglary at Chertsey.

Dickens also took advantage of the river for exercise, as is shown in his letter to MacLise, dated 28th June 1839:

‘Beard is hearty, new and thicker ropes have been put up at the tree, the little birds have flown, their very nests have disappeared, the roads about are jewelled after dusk by glowworms, the leaves are all out and the flowers too, swimming feats from Petersham to Richmond Bridge have been achieved before breakfast, I myself have risen at 6 and plunged head foremost into the water to the astonishment and admiration of all beholders…’

Among the other celebrities at that time resident in the area were the Berry sisters, Agnes and Mary, who entertained Dickens to dinner on July 1st 1839. In June Dickens had received a letter from the Rev. Sydney Smith:

‘The Miss Berrys, now at Richmond, live only to become acquainted with you and have commissioned me to request you to dine with them Friday, the 29th or Monday July 1st to meet a Canon of St. Paul’s, the Rector of Combe Florey and the Vicar of Halberton [i.e. Smith himself, who was all three] – all equally well known to you; to say nothing of other and better people. The Miss Berrys and Lady Charlotte Lindsay have not the smallest objection to be put into a Number, but, on the contrary, would be proud of the distinction; and Lady Charlotte, in particular, you may marry to Newman Noggs. Pray come, it is as much as my place is worth to send them a refusal.’

According to Chancellor in his History and Antiquities of Richmond, Kew, Petersham, Ham etc. (1894), Dickens also lived for a time at Woodbine Cottage which was situated near Elm Cottage in the Petersham Road. There seems to be no mention of this, however, in the novelist’s published letters.

Dickens’s sojourn at Petersham lasted until the end of August 1839 and we next hear of him in the vicinity in May 1840. Early in that month he wrote to Forster:

‘We are to be heard of at the Eel Pie House, Twickenham where we shall dine at half past five or thereabouts and where we will take care of you if you come.’

The novelist must have visited this popular establishment on at least one previous occasion, for in Nicholas Nickleby (the last instalment of which appeared in October 1839), Morleena Kenwigs travels to Eel Pie Island by steamer from Westminster Bridge ‘to make merry upon a cold collation, bottled-beer, shrub and shrimps and to dance to the music of a locomotive band.’

In Little Dorrit (1857), the Meagles cottage was by the river between Richmond Bridge and Teddington Lock:

‘It stood in a garden and was defended by a goodly show of handsome trees and spreading evergreens. It was made of an old brick house, which a part had been altogether pulled down, and another part had been changed into the present cottage…within view was the peaceful river, and the ferry boat.’

Finally, there is the vivid description in Great Expectations of the house by Richmond Green, to which Estella is sent by Miss Haversham:

‘…a staid old house, where hoops and powder and patches, embroidered coats, rolled stockings, ruffles and swords, had their court days many a time. Some ancient trees before the house were still cut into fashions as formal and unnatural as the hoops and wigs and stiff skirts; but their own allotted places in the great procession of the dead were not far off, and they would soon drop into them and go the silent way of the rest.’

Suggestions for further reading

Ackroyd, Peter / Dickens. 1990

Dickens, Charles / Letters; edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey and Kathleen Tillotson. Volume 1: 1820-39. 1965 / Volume 2: 1840-41. 1969 / Volume 3: 1842-43. 1974

Dictionary of National Bibliography article on Charles Dickens

Forster, John / The life of Charles Dickens. 3 volumes. 1872-1874

Hardwick, Michael and Mollie / Charles Dickens’ Surrey. (Surrey Life, volume 2. no. 3. December 1972)

Sack, O. / The Star and Garter, Richmond: Dickens’ association with it and the district. (The Dickensian, vol.8, no.1, January 1912, pp.14-16)

More information on other people and places of interest in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames is available from the Local Studies Library & Archive.