Richmond Read-along 93

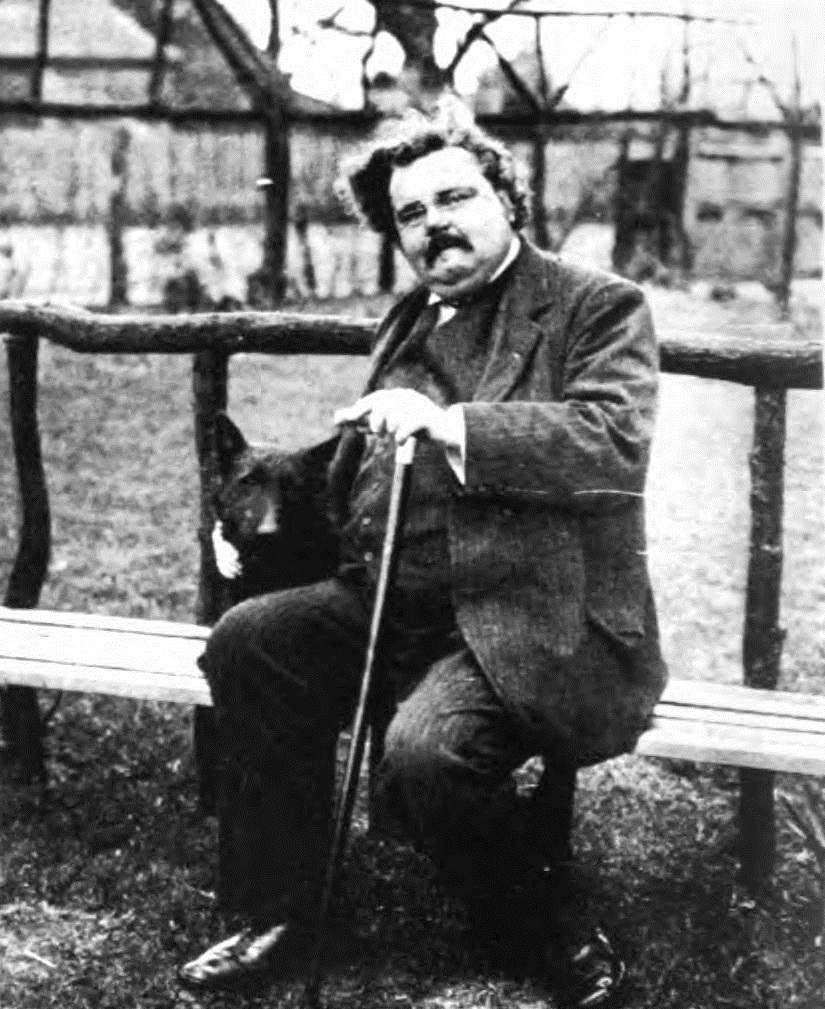

Welcome back to the Richmond Read-along! Today we’re reading a piece from G. K. Chesterton. Chesterton was a philosopher, novelist, biographer, essayist, and above all a man-about-town who revelled in his writing and in literary circles. He is often cited as a master of paradox; certainly his love of highlighting and exploring the paradoxical helps make his early work and multitudinous essays surprising, creative and often insightful. He was markedly eccentric, cutting a remarkable figure in his trademark cloak and hat, constantly jotting down his thoughts and carrying around with him myriad books and papers. His biographies were an excellent example of his laissez-faire attitude towards facts, but also show how his identification with his subjects was employed to remarkably effect; while often criticised by experts, his biographies were widely adored by readers. His fiction was likewise sparkling and entertaining, particularly when he pulled in his love of paradox and the absurd. His works were often fantastical and in some cases would fall under current classification of science fiction, dystopic or utopic writing, and fantasy. Even his most niche and obscure works are still widely appreciated for his engaging prose.

Chesterton later became devoutly religious, having all his life been committed to various causes. His great humanitarianism was characterised by his generosity of character, love of life and unrepenting optimism. However, his love of people and equality – shown by his abhorrence at the idea of eugenics embodied in debates of the time of forcibly sterilising those with disabilities, defence of the working class as equally as deserving as the wealthy, and other arguments – was marred by his antisemitism. While he defended himself against these charges by claiming he was simply supporting the case for Jewish people’s right to self-determination (and indeed spoke out early in horror at Hitler and Nazi policies) his protest falls flat in the face of Jewish caricatures and scapegoating in his works. While he is sometimes quoted as being unwell or not robust, Chesterton lived until 62 – longer than many authors featured in our Read-along – leaving behind a wealth of writing, countless lovers of his work, an impressive monetary wealth and even an honour bestowed upon him by the Pope for his later Catholic writings.

The Ballade of a Strange Town

My friend and I, in fooling about Flanders, fell into a fixed affection for the town of Mechlin or Malines. Our rest there was so restful that we almost felt it as a home, and hardly strayed out of it.

We sat day after day in the market-place, under little trees growing in wooden tubs, and looked up at the noble converging lines of the Cathedral tower, from which the three riders from Ghent, in the poem, heard the bell which told them they were not too late. But we took as much pleasure in the people, in the little boys with open, flat Flemish faces and fur collars round their necks, making them look like burgomasters; or the women, whose prim, oval faces, hair strained tightly off the temples, and mouths at once hard, meek, and humorous, exactly reproduced the late mediaeval faces in Memling and Van Eyck.

But one afternoon, as it happened, my friend rose from under his little tree, and pointing to a sort of toy train that was puffing smoke in one corner of the clear square, suggested that we should go by it. We got into the little train, which was meant really to take the peasants and their vegetables to and fro from their fields beyond the town, and the official came round to give us tickets. We asked him what place we should get to if we paid fivepence. The Belgians are not a romantic people, and he asked us (with a lamentable mixture of Flemish coarseness and French rationalism) where we wanted to go.

We explained that we wanted to go to fairyland, and the only question was whether we could get there for fivepence. At last, after a great deal of international misunderstanding (for he spoke French in the Flemish and we in the English manner), he told us that fivepence would take us to a place which I have never seen written down, but which when spoken sounded like the word “Waterloo” pronounced by an intoxicated patriot; I think it was Waerlowe.

We clasped our hands and said it was the place we had been seeking from boyhood, and when we had got there we descended with promptitude.

For a moment I had a horrible fear that it really was the field of Waterloo; but I was comforted by remembering that it was in quite a different part of Belgium. It was a cross-roads, with one cottage at the corner, a perspective of tall trees like Hobbema’s “Avenue,” and beyond only the infinite flat chess-board of the little fields. It was the scene of peace and prosperity; but I must confess that my friend’s first action was to ask the man when there would be another train back to Mechlin. The man stated that there would be a train back in exactly one hour. We walked up the avenue, and when we were nearly half an hour’s walk away it began to rain.

…..

We arrived back at the cross-roads sodden and dripping, and, finding the train waiting, climbed into it with some relief. The officer on this train could speak nothing but Flemish, but he understood the name Mechlin, and indicated that when we came to Mechlin Station he would put us down, which, after the right interval of time, he did.

We got down, under a steady downpour, evidently on the edge of Mechlin, though the features could not easily be recognised through the grey screen of the rain. I do not generally agree with those who find rain depressing. A shower-bath is not depressing; it is rather startling. And if it is exciting when a man throws a pail of water over you, why should it not also be exciting when the gods throw many pails? But on this soaking afternoon, whether it was the dull sky-line of the Netherlands or the fact that we were returning home without any adventure, I really did think things a trifle dreary. As soon as we could creep under the shelter of a street we turned into a little café, kept by one woman. She was incredibly old, and she spoke no French. There we drank black coffee and what was called “cognac fine.” “Cognac fine” were the only two French words used in the establishment, and they were not true. At least, the fineness (perhaps by its very ethereal delicacy) escaped me. After a little my friend, who was more restless than I, got up and went out, to see if the rain had stopped and if we could at once stroll back to our hotel by the station. I sat finishing my coffee in a colourless mood, and listening to the unremitting rain.

…..

Suddenly the door burst open, and my friend appeared, transfigured and frantic.

“Get up!” he cried, waving his hands wildly. “Get up! We’re in the wrong town! We’re not in Mechlin at all. Mechlin is ten miles, twenty miles off—God knows what! We’re somewhere near Antwerp.”

“What!” I cried, leaping from my seat, and sending the furniture flying. “Then all is well, after all! Poetry only hid her face for an instant behind a cloud. Positively for a moment I was feeling depressed because we were in the right town. But if we are in the wrong town—why, we have our adventure after all! If we are in the wrong town, we are in the right place.”

I rushed out into the rain, and my friend followed me somewhat more grimly. We discovered we were in a town called Lierre, which seemed to consist chiefly of bankrupt pastry cooks, who sold lemonade.

“This is the peak of our whole poetic progress!” I cried enthusiastically. “We must do something, something sacramental and commemorative! We cannot sacrifice an ox, and it would be a bore to build a temple. Let us write a poem.”

With but slight encouragement, I took out an old envelope and one of those pencils that turn bright violet in water. There was plenty of water about, and the violet ran down the paper, symbolising the rich purple of that romantic hour. I began, choosing the form of an old French ballade; it is the easiest because it is the most restricted—

“Can Man to Mount Olympus rise,

And fancy Primrose Hill the scene?

Can a man walk in Paradise

And think he is in Turnham Green?

And could I take you for Malines,

Not knowing the nobler thing you were?

O Pearl of all the plain, and queen,

The lovely city of Lierre.

“Through memory’s mist in glimmering guise

Shall shine your streets of sloppy sheen.

And wet shall grow my dreaming eyes,

To think how wet my boots have been

Now if I die or shoot a Dean——”

Here I broke off to ask my friend whether he thought it expressed a more wild calamity to shoot a Dean or to be a Dean. But he only turned up his coat collar, and I felt that for him the muse had folded her wings. I rewrote—

“Now if I die a Rural Dean,

Or rob a bank I do not care,

Or turn a Tory. I have seen

The lovely city of Lierre.”

“The next line,” I resumed, warming to it; but my friend interrupted me.

“The next line,” he said somewhat harshly, “will be a railway line. We can get back to Mechlin from here, I find, though we have to change twice. I dare say I should think this jolly romantic but for the weather. Adventure is the champagne of life, but I prefer my champagne and my adventures dry. Here is the station.”

…..

We did not speak again until we had left Lierre, in its sacred cloud of rain, and were coming to Mechlin, under a clearer sky, that even made one think of stars. Then I leant forward and said to my friend in a low voice—“I have found out everything. We have come to the wrong star.”

He stared his query, and I went on eagerly: “That is what makes life at once so splendid and so strange. We are in the wrong world. When I thought that was the right town, it bored me; when I knew it was wrong, I was happy. So the false optimism, the modern happiness, tires us because it tells us we fit into this world. The true happiness is that we don’t fit. We come from somewhere else. We have lost our way.”

He silently nodded, staring out of the window, but whether I had impressed or only fatigued him I could not tell. “This,” I added, “is suggested in the last verse of a fine poem you have grossly neglected—

“’Happy is he and more than wise

Who sees with wondering eyes and clean

The world through all the grey disguise

Of sleep and custom in between.

Yes; we may pass the heavenly screen,

But shall we know when we are there?

Who know not what these dead stones mean,

The lovely city of Lierre.’”

Here the train stopped abruptly. And from Mechlin church steeple we heard the half-chime: and Joris broke silence with “No bally HORS D’OEUVRES for me: I shall get on to something solid at once.”

L’Envoy

Prince, wide your Empire spreads, I ween,

Yet happier is that moistened Mayor,

Who drinks her cognac far from fine,

The lovely city of Lierre.

You can find this piece in “Tremendous Trifles” on Project Gutenberg, one of Chesterton’s many collections of essays. Richmond upon Thames Borough Library members can read more about Chesterton in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Join us tomorrow for the next Richmond Read-along!