Witches

In libraries around the world, the Dewey Decimal System is used to classify books by subject. Tucked away in the 100s (Philosophy and Psychology) is 133.4. This section might be small or non-existent in some selections, and larger in others, although in all libraries it is a little bit mysterious. 133.4 is the Dewey Decimal call number that denotes Witchcraft.

Witchcraft and witches are a topic that captures the imagination of young and old alike. There have been witch beliefs in nearly every society, and they have proven remarkably resilient. While the archetypal “witch” varies, witchcraft always denotes something that exists on the edges – of society, of reality, of knowledge.

Modern witchcraft

The modern, western witch is one of two things. The first is a self-identifying witch, who typically is reclaiming the word from its negative connotations. This witch may have religious or spiritual practices that are tied to their identity as a witch. Wicca, popularised through TV programmes such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Charmed, is the most widely known “witchy” religion. However, self-defined witches may belong to any one of many traditions, may “cherry-pick” their beliefs and rituals from multiple traditions, or may practice outside any specific tradition. Modern witches may steer clear of stereotypes, or they may embrace and subvert them.

Stereotypes

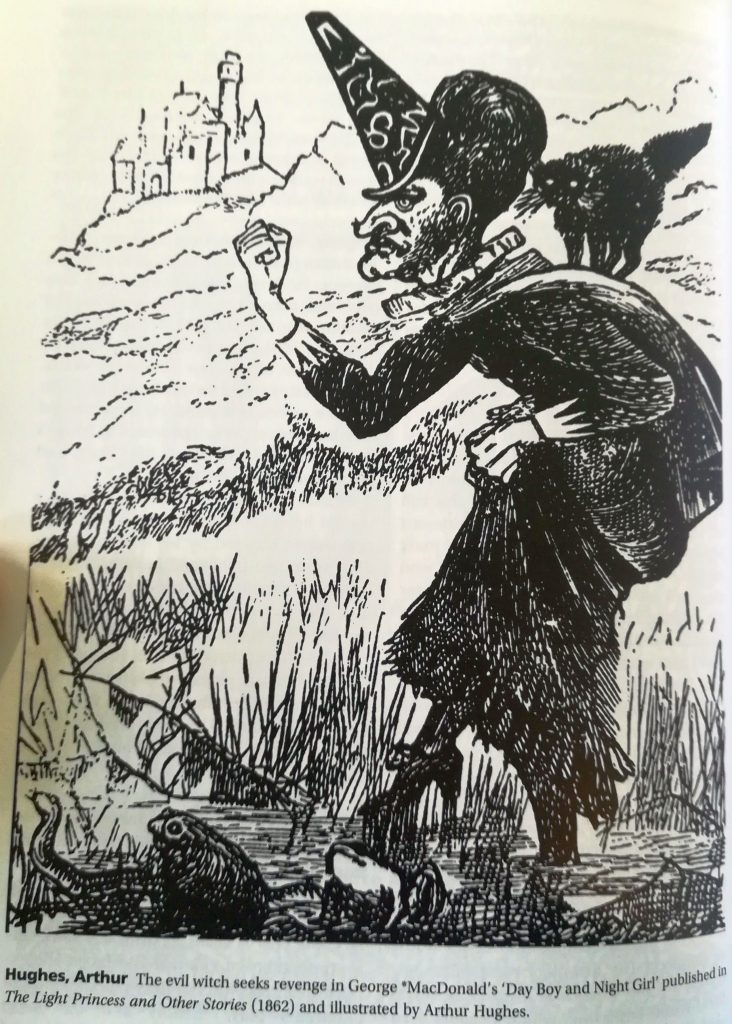

The other use of the word witch is to invoke the archetypal “witch”. Most people have an idea of what a stereotypical witch looks like. If pushed, you would probably describe a witch as an elderly woman, probably with warts and a long, pointed nose and chin. Wearing mostly black, she has a pointed hat and boots. She has a black cat, a broomstick, a cauldron, and an evil cackle. She can perform magic of some kind – making things appear and disappear, making potions or controlling objects and animals. Despite the current trend for witches producing a wide array of mostly positive portrayals in pop culture, the stereotypical witch is still “evil”. At the least, she is unlikely to be “good” – unless specified as a “white witch”.

This stereotypical witch is behind the word when it is used as an insult (normally against women, to signify callousness, cruelty, ugliness, sexual desire, manipulation, lust for power, and other un-womanly qualities.) It is also behind witch or occult panics. This association of the witch and magic with lawlessness, uncontrolled power and moral ambiguity has led to US churches burning Harry Potter books and denouncing them as corrupting influences that lead children to Satanism. More light heartedly, this invoking of the witch stereotype is behind the witch as a costume or character in books and on Hallowe’en. The pointed witches hat even appears in the TV series Grimm, where witches are called hexenbeasts and have cultural differences.

Liminality

One of the most consistent traits of magic across cultures is that it is marginal and mysterious. Magic, whether in the form of witches, fairies, elves or enchantments, exists in the spaces which are neither one thing or the other. Goblins and fairies traditionally appear around boundaries such as doors and windows, where they sneak in through the between-spaces. Liminal spaces are places between – not part of a society but not outside of it either. Witches, both as a stereotype and as individuals who were accused of witchcraft, often exist in a liminal, uncertain space. This is part of the fear of witches and magic – that they are outside society’s rules, outside the law, even outside of traditional morality, and so cannot be trusted.

Old women without a family, who don’t fit in to society’s roles of mother, grandmother, wife or matriarch but refuse to go away quietly, are associated with witchcraft. Neither one thing nor the other, they defy categorisation and – when mixed with magic and superstition – become a dangerous unknown. Witch as an insult is often used against women who are unmarried or have no children, or seem to overpower the men in their life. They don’t fit in to society’s idea of what a woman should be, challenging and defying their assigned roles. On the edges of their proper role, they become a possible threat.

Magic and witchcraft was a way to put a name to the threat. Individuals comfortable in a new or different role had some mastery of the unknown – in the way that magic is mastery over the unknown.

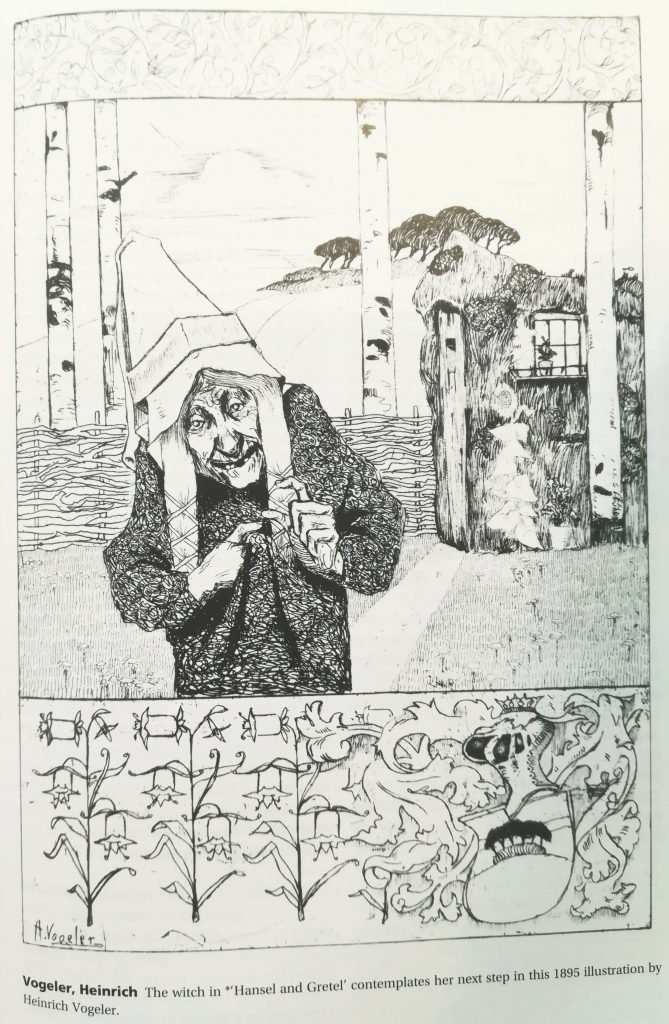

The literary witch

The character of the witch has been popular at least since stories were written down. Hecate was a goddess from Ancient Greece. Her name is now synonymous with witchcraft, power and evil. Hecate originally had both benevolent and dark characteristics, and she helped the goddess Demeter to find her daughter Persephone when Hades stole Persephone away to the underworld. Circe was a witch of antiquity who played a part in Homer’s Odyssey. From the Grimm fairytales to Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, from The Chronicles of Narnia to Begone the Raggedy Witches, witches have endured cultural and historical shifts to remain one of the most enduring character tropes in popular culture.

While the witch in literature may not always be irredeemably evil, she is always powerful. Even the clumsy protagonists of The Worst Witch and Winnie the Witch are able to fly and transmogrify, even if they don’t always manage to achieve the desired results. The White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is powerful enough to hold a whole world in bitter winter. Witches are forces to overcome, or incredible allies in a fight against evil. Their power and ambiguity makes witches appealing and interesting characters.

Fiction aside, there are a number of other books that have been tied to witches and witchcraft. Grimoires – books used for magic – have been widely created and highly sought after. Even religious books such as the Bible were used to create charms and curses.

Witch panics

Possibly the most infamous book about witchcraft is not a purported book of spells, but a book of punishment. Heinrich Kramer wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, commonly translated as “Hammer of Witches,” in the 1400s. Kramer was known for his vehement hatred of witchcraft and those accused, and the extreme methods he believed were justified in the trial of witches. Some scholars argue that parts of the book may be largely humorous (for example the chapters on witches stealing penises and keeping them in nests). However, the Malleus Maleficarum still made a significant contribution to the European witch panics which peaked in the 16th-18th century.

These infamous panics spanned Europe and even made it to America, the Salem witch trials being the best known example. While the precise number of people killed is unknown, some estimates put the death toll in the millions. More precise estimations are normally in the low tens of thousands, still a shocking number.

The European witch panics of the early modern period are still studied today, as are the Salem witch trials. They are the subject of many books and academic papers, as well as being popular topics for amateur historians, self-described modern witches and feminist theorists, due to the gender bias among those accused. While no one theory withstood the test of time, religious extremism, mass hysteria and even ergot poisoning were all suggested as the cause of various witch panics. The current thinking leans towards less dramatic explanations. Social and economic upheaval and the beliefs of the times – as well as the enduring fascination with witches throughout human history – are all likely factors in this particular spate of witch hunts.

Witch hunts

When witch hunting is mentioned, these witch panics of Salem and Britain’s Pendle witches spring to mind. However witch panics, trials and even executions were happening long before – and after – the 1500s. Witch hunts are possibly as old as the symbol of the witch herself. Records exist of witchcraft accusations in Ancient Rome. There are even reports of hundreds of accused witches being executed together, although mass executions are the exception and not the rule.

Far from being a relic of the past, there are also modern day witch hunts. Some provinces of India and African countries occasionally make headlines when witch hunts result in deaths. People sometimes accuse children, and drive them from their homes. In the US and UK, the “Satanic panics” of the 80s and 90s were linked to accusations of witchcraft. People were accused of dark rituals, Satanism, and child abuse, and often weren’t exonerated until years later. Less literally, the term “witch hunt” often now refers to moral panics. Individuals or groups often invoke the term when they feel persecuted with no basis. Belief in malevolent witches may be less common in some places, but witch hunts can still happen.

Witches in vogue

The popularity of witches and magic shows no signs of abating. The Harry Potter empire continues to churn out movies, merchandise and new stories. Books such as the hotly anticipated Circe show that the current appetite for witches continues to rise. “Witchy” aesthetics proliferate on social networks such as Instagram. Hashtags such as #instawitch and #witchesofinstagram tag popular accounts like The Hoodwitch that mix beautifully crafted pictures with folk knowledge, herbs, crystals, and female empowerment. Stylised “witchy” items and crystals are in shops outside of Hallowe’en. Even Starbucks introduced a “Crystal Ball Frappucino” throughout America in March 2018.

Religious witchcraft is also on the rise. Through organised covens, Wicca and Paganism, or eclectic faith, people seem more willing than ever to openly discuss religious witchcraft. As well as Instagram, witches use other social media to organise and share knowledge, through blogs, Tumblr and Facebook groups. It could be an alternative to traditional church structure, a desire to reconnect with nature, a reputation for fighting oppression or the appeal of individually tailored beliefs. Whatever the root causes, Wiccan and pagan religions are becoming mainstream. The Ministry of Justice has recognised pagan religions, and even has pagan chaplains available for prisoners.

In an age where we like to think we no longer have need for superstition, witches are still capturing imaginations, giving shape to fears and rebellions, celebrating sabbats, healing with herbs and cackling in the shadows. One thing seems certain: witches aren’t going anywhere.

Bibliography and further reading

Grimoires: a history of magic books, by Owen Davies

Malleus Maleficarum, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, translated by Montague Summers

Histories Books IV-V & Annals Books I-III, by Cornelius Tacitus, translated by John Jackson

Witchcraft: a very short introduction, by Malcolm Gaskill

The Triumph of the Moon: a history of modern pagan witchcraft, by Ronald Hutton

The Witch: a history of fear, from ancient times to the present, by Ronald Hutton

The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland, by Steve Roud

The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, edited by Jack Zipes

The Encyclopedia of Mythology: Norse, classical, Celtic, by Arthur Cotterell

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, translated by Jack Zipes

The Witches Trilogy (Equal Rites/Wyrd Sisters/Witches Abroad), by Terry Pratchett

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C. S. Lewis

Begone the Raggedy Witches, Celine Kiernan

The Worst Witch, by Jill Murphy

Winnie the Witch, by Valerie Thomas and Korky Paul

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, by J. K. Rowling

Witchcraft: A Very Short Introduction Malcolm Gaskill

[Iona, Library Assistant]