Follow the Drum: Christmas 1916

Christmas 1916. The third Christmas of the War.

In this article we consider daily life in the Borough at the time of the third Christmas of the War. It was a period of stark contrasts and contradictions for all sections of the local community. German submarine successes at this point in the war were severely damaging British shipping and supply routes and creating a tremendous strain on the economy nationally and locally. Maintaining morale was a difficult challenge in these trying circumstances.

Missing but not in action

1916 had been a year that started with the introduction of conscription. One outcome of this was manifested on a day-to-day level with the weekly publication of lists of missing men in the local papers. The Recruiting Office had a responsibility for tracing those who were missing prior to service in the forces and possibly even while in service (for example, John Dolan on the list of Married Men has ‘Richmond Camp, Richmond’ as the address). Initially intended to support the process of conscription, it was an attempt to systematise and maintain the supply of men to fight the War at the front. A constant need for recruits mirrored the need for continual supplies of war essentials such as shells and munitions in this new industrialised era of international confrontation. The list was also intended to publish outcomes when men were successfully traced (Stanley Mills of 3 Paradise Cottages, Richmond, is included at the end of the list from December 1916 ‘The Thames Valley Times’ as ‘accounted for’).

1916 had been a year that started with the introduction of conscription. One outcome of this was manifested on a day-to-day level with the weekly publication of lists of missing men in the local papers. The Recruiting Office had a responsibility for tracing those who were missing prior to service in the forces and possibly even while in service (for example, John Dolan on the list of Married Men has ‘Richmond Camp, Richmond’ as the address). Initially intended to support the process of conscription, it was an attempt to systematise and maintain the supply of men to fight the War at the front. A constant need for recruits mirrored the need for continual supplies of war essentials such as shells and munitions in this new industrialised era of international confrontation. The list was also intended to publish outcomes when men were successfully traced (Stanley Mills of 3 Paradise Cottages, Richmond, is included at the end of the list from December 1916 ‘The Thames Valley Times’ as ‘accounted for’).

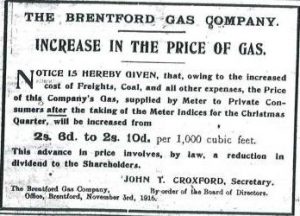

Households were under immense pressure to make ends meet on all levels: putting food on the table without the traditional breadwinner; paying the bills for utilities; staying warm and at this stage in the war keeping clothing in a good state of repair were some of the basic and more immediate needs. The cost of living was rising, as can be seen in the notice published throughout December 1916 from the Brentford Gas Company, announcing the increase in price of 4d per cubic foot for the supply gas to customers. Notification was also being given by these means to the shareholders of the reduction in the dividend which was being legally imposed. Potentially in some households a double blow to domestic finances and a direct result of the price rise to the consumer. The third Christmas of the War meant difficult times all over.

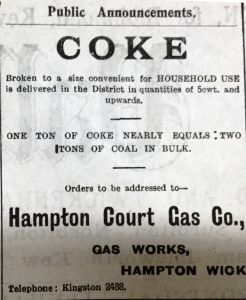

At this time people were being encouraged to use coke as a more economical form of fuel to heat their homes. As a commodity, coal was required for the war effort and consequently was costly and in short supply. Due to the shortage of man-power mining for coal itself was yet more challenging.

The insufficiency of street lighting (subject to economies as well) at this time on winter nights was documented in Twickenham Urban District Council Minutes and is indicative of the great need to conserve supplies and save energy. (p 156 Twickenham Urban District Council Minutes January 2017 L 352 T1). Damage to street lights was reported in Heath Road and Church Lane, the likely cause being vehicles colliding with them over-night in the dark.

Council action

Food shortages had been under discussion at Council level in December 1916 (motion by Alderman Carless, p 29 Minute of Richmond Council, L352). Beyond the period of the third Christmas of the war and into the New Year (by September 1917) Richmond Council established a Food Control Committee. Sugar distribution and the pricing of meat, flour and milk would fall under its remit as well as monitoring the registration of Potato dealers and supervising their wholesale and retail prices. The Council also took action when any contraventions to regulations occurred by means of prosecutions (pp 99, 108 & 119 Minutes of Richmond Council, June 1917, L 352). The Coal Supply Committee was formed to respond to the Household Coal Distribution Act of 1917). (pp 129 – 30 Minutes of Richmond Council, September 1917, L 352). The national crisis was managed locally to secure supplies and rationalise the situation.

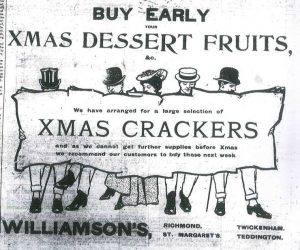

This notice put in the local paper by Williamsons demonstrates how low supplies of fresh produce were in reality. The suppliers are announcing the arrival of fresh fruit while informing customers that it will only be available during a particular week in December 1916 if they wish to purchase it as a treat for Christmas. It was also a clever marketing strategy to boost sales as customers are encouraged to ‘buy early’. Food supplies were far from secure and this effected life on a daily basis at the local level.

This notice put in the local paper by Williamsons demonstrates how low supplies of fresh produce were in reality. The suppliers are announcing the arrival of fresh fruit while informing customers that it will only be available during a particular week in December 1916 if they wish to purchase it as a treat for Christmas. It was also a clever marketing strategy to boost sales as customers are encouraged to ‘buy early’. Food supplies were far from secure and this effected life on a daily basis at the local level.

Stories concerning court cases and criminal activities involving the supply of meat can be referenced in the Richmond & Twickenham Times such as December 9th 1916: ‘Settling a butcher’s bill’ and on the 16th ‘The Alleged Army Meat Thefts’. These incidents also illustrate the seriousness of the food supply situation.

Fare increases

Local councils were developing new strategies for dealing with problems faced by their local communities that were a direct outcome of the war. Early in the new year (February 1917) a response was being developed by Richmond, Wimbledon and Ealing to counter fare increases on the railway. The 3 boroughs were approaching the Railway Executive Committee seeking inclusion in a zone of places on the District Railway where no increased fare would be charged to passengers. The Richmond (Surrey) Chamber of Commerce also corresponded with the Railway Executive Committee, suggesting that tickets up to the value of 2s 6d should be free. However, the industry committee argued that they were ‘acting in the National Interest with definite objects in view’ in issuing the order to increase fares. However, no recommendation was made on the subject at this point (pp 48 – 9 Minutes of Richmond Council, 1916 – 17, L 352).

Early closures of shops during the winter months at this stage in the war were used to control the sales of refreshments, sweets and chocolate. The Secretary of State had issued a general order in October 1916, followed by an amendment (letter from the Under-Secretary of State) concerning this matter. There was a brief concession to the Christmas period however as the early closure of shops order was completely suspended between 14th and 23rd December 1916. This was an attempt to boost morale for the festivities such as they were. (p 116 Twickenham Urban District Council Minutes December 2017 L 352 T1).

An Appeal: an early form of crowd-funding?

While significant shortages and economic pressures created dilemmas for householders attempting to budget, an appeal was launched via the local press ‘our Christmas fund for the wounded’. There were huge financial constraints and yet they did not impede the bid to provide gifts for those men lying wounded in the local hospitals. The local population dug deep on both the financial and emotional level. A good source of information about the success of the appeal appears in the Richmond & Twickenham Times throughout late November and the month of December 1916.

The figures for the appeal were published weekly and names of subscribers were meticulously listed. We can learn about the lengths that people went to in order to support their men. For example, ‘M. S.’ from Amyand Park, writes in the edition of December 2nd 1916, that: ‘Instead of exchanging our small birthday presents in the usual way my friend and I thought we would be content with each other’s good wishes this year and give “our boys” the benefit, as they deserve all they can get. My share, therefore, is herewith enclosed for the “Christmas Comforts Fund”.’

Full details of where the wounded were actually located in the borough were outlined (for example, the Star and Garter Home, Richmond Royal Military Hospital, the South African Military Hospital, Hanworth Park Red Cross Hospital amongst others) and the total number of beds supported was 1,381. The newspaper used a clever technique to emphasise the great need of these soldiers starkly contrasted with the shortness of time by publishing headlines every week announcing the time that remained: ‘Only seven days more! Help still needed for the Christmas Comforts Fund!’ (the Richmond & Twickenham Times 9th December 1916).

The donations were a shilling and these are referred to as our ‘Splendid Shillings, those from a slender store.’ The paper demonstrated an awareness of how lean times were and yet at this stage had received a total of 3,306 shillings.

By 23rd December 1916 the success of the appeal was heralded: ‘Nearly 6,000! Success of Christmas Comforts fund. The “Share Out”. How Our Readers’ Gifts were Distributed’.

The Appeal was soundly established by the Third Christmas of the War. An example of this was that they brought in funds raised by the “Chiswick Times” (757 shillings) to be combined with the total from the borough.

Employment

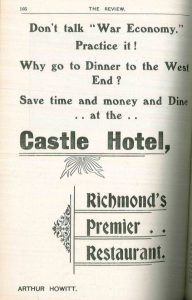

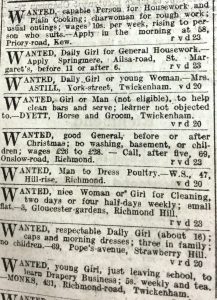

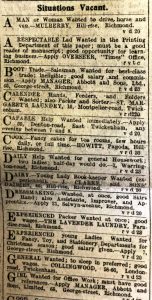

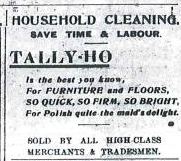

Roles were changing at home and also in the world of employment where women were now urgently needed to replace the men who had been called up, despite a somewhat grudging recognition of this fact. One example of this can be seen as early as 1915 in the minutes for Teddington Urban District Council where due to the difficulties in finding a boy to act as Junior Assistant they admit that they need to recruit a girl as it is so problematic. There are no further references noted to how this situation developed or to the salary level for the new recruit. Women were now looking for work that would offer improved wages with more flexible terms and conditions to supplement the household income (some of these trends can be traced in the Situations Wanted classifieds of the Thames Valley Times and the Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 1916). They were moving away from traditional domestic situations which opened up a gap in this area of the jobs market at that time. This represented a crisis for households that prior to the war had depended on servants and hired help to maintain a certain standard of living (reflected in the Situations Vacant classifieds in the Thames Valley Times and the Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 1916). Social changes were rapidly evolving due to these new contexts brought about by the crisis. Now the trend was increasingly towards the need to save time and labour on domestic chores.

Roles were changing at home and also in the world of employment where women were now urgently needed to replace the men who had been called up, despite a somewhat grudging recognition of this fact. One example of this can be seen as early as 1915 in the minutes for Teddington Urban District Council where due to the difficulties in finding a boy to act as Junior Assistant they admit that they need to recruit a girl as it is so problematic. There are no further references noted to how this situation developed or to the salary level for the new recruit. Women were now looking for work that would offer improved wages with more flexible terms and conditions to supplement the household income (some of these trends can be traced in the Situations Wanted classifieds of the Thames Valley Times and the Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 1916). They were moving away from traditional domestic situations which opened up a gap in this area of the jobs market at that time. This represented a crisis for households that prior to the war had depended on servants and hired help to maintain a certain standard of living (reflected in the Situations Vacant classifieds in the Thames Valley Times and the Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 1916). Social changes were rapidly evolving due to these new contexts brought about by the crisis. Now the trend was increasingly towards the need to save time and labour on domestic chores.

One of the local papers, the Richmond & Twickenham Times, also ran a weekly series of articles about developments at the Whitehead Aircraft factory in Richmond called ‘Whitehead Aircraft Notes’.

The Christmas feature (December 23rd 1916) focused on the ‘Increase of women Employees. The Skilled Workman’s Training’:

‘It is interesting to see how women are gradually taking up all kinds of work in connections with munitions that a couple of years ago would have appeared ridiculous. Hundreds of women were reported as working in the ‘doping and varnishing’ departments, in the fabric shops … where they are employed in covering the wings with linen, and in some of the wood working shops where they are engaged in sand-papering various wood parts of the machine. But to find women in the assembling shops, busy working away on the delicate task of building up the wings, taking the place of highly skilled men was certainly a revelation’. (Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 23rd 1916).

This response, typical of its day, to the expansion of the aircraft industry demonstrates how traditional attitudes were fast overtaken by the actualities of rapid social change resulting from the war. For some it was clearly a struggle to assimilate new realities that over-turned pre-existing conceptions about roles and responsibilities. This climate of uncertainty and constant change characterised the Third Christmas of the war.

This response, typical of its day, to the expansion of the aircraft industry demonstrates how traditional attitudes were fast overtaken by the actualities of rapid social change resulting from the war. For some it was clearly a struggle to assimilate new realities that over-turned pre-existing conceptions about roles and responsibilities. This climate of uncertainty and constant change characterised the Third Christmas of the war.

One way of supplementing the household income was to let a room to a lodger and there was a range of such accommodation advertised in the classifieds. Noticeably some advertisements were aimed at women workers while others were demonstrably intolerant of ‘outsiders’ (‘no foreigners’ is a strict condition included in terms advertised in the ‘nicely furnished bedsit… suit lady or gentleman…’). Moving into the fourth year of the war and with family members fighting on the front, there was no tolerance or trust apparent for anyone or anything different. This was a time of total war even at home.

The need for practical pastoral care of the ‘new’ working woman was assumed by organisations such as the Mabys (Metropolitan Association for the Befriending of Young Servants) and also the Young Women’s Christian Association or YWCA (the latter can be seen in the advertisement below from the Thames Valley Times, December 1916).

Life and death questions

The Volunteers Act of 1916 had been implemented and also local Tribunals were considering cases and appeals concerning military service for some men. An example of one occupation that was under scrutiny was that of Gravedigger. The Appeal Tribunal had granted temporary exemption from military service to E. B. Ratcliffe until 31st January 1917 due to the crisis across London about burials. (p 164 Twickenham Urban District Council Minutes January 2017 L 352 T1). Grave digging was considered an important and necessary work but due to the war it had been impossible across London cemeteries to find ‘able or willing substitutes’. Over the course of several days there had been problems in burying the dead within a respectful period of time and the UDC was taking action to prevent such a grim situation: ‘… to avoid the unpleasant experience’. They were aiming for the Appeal Tribunal to re-hear the case. The consequences of the ‘European Crisis’ were indeed complex and upsetting.

Clothing

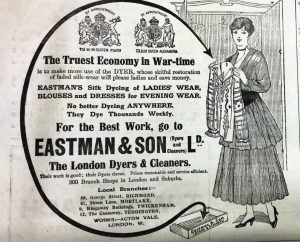

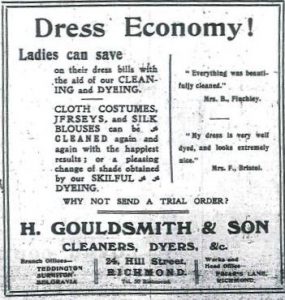

Economising wherever possible was regarded as a highly patriotic activity. It was an absolute necessity on the domestic level and one area where it became essential as the war progressed was clothing. Women at home in those days were generally able to sew (it was an expectation and part of their education). They were extending these skills to repair clothes to give them a new lease of life. There were frequent advertisements in the local papers seeking seamstresses and offering such positions as well as local laundries/cleaners offering to dye clothing (in some instances sadly for funeral purposes). Eastman & Co regularly advertised in this way (Richmond & Twickenham Times December 1916) and had the extra edge in the market as they carried the seal of approval from 2 royal patrons (H.M. Queen Mary and H.M. Queen Alexandra). This business was clearly aiming at the upper end of the market but we can see that the notice by Gouldsmith’s concerned ‘Dress Economy’ so this was regarded as a popular and practical solution to an everyday problem.

Sewing was also a patriotic activity in other ways: shirts for the troops; linens for the hospitals and providing items for fundraising sales of goods that were a common occurrence (there are many references to these activities in the local press of the day). There were even patriotic songs about such activities, for example, ‘Sister Susie’s Sewing Shirts for Soldiers’ recorded by Al Jolson. The lyrics appear in the Surrey Volunteer Review 1915 – 17 (pp 60 – 61) which is accessible in the Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library & Archive search room in the Old Town Hall.

This song was taken up by the local Volunteers as a patriotic song and more than likely would also have been adopted as a marching song while on exercises or route marches across the county. It was a very popular song indeed and according to the Review magazine (September 1915) was second only to Tipperary which was ‘no doubt, the greatest song of the war’ (the Review). They had acquired the rights from the publishing firm Francis, Day & Hunter, to publish the words as Mr Frederick Day (a partner in the music publishing business) was a member of the Barnes Company.

‘Sister Susie’s sewing shirts for soldiers,

Such skill at sewing shirts our shy young sister Susie shows!

Some soldiers send epistles, say they’d sooner sleep in thistles

Than the saucy, soft, short shirts for soldiers Sister Susie sews.’ (Chorus, p 61 the Surrey Volunteer Review 1915 – 17).

Economy in Wartime

The need for war-time economy is a recurring theme and the pressure to be patriotic was very real for women on the home front. There are numerous references to women reflecting whether or not they were being perceived as rising to the challenge. The implicit expectation was that they would need to make sacrifices at home and yet maintain morale while acting patriotically. Such constraints and pressure had to be factored into daily life.

To support and educate those who were interested in the best ways to economise, some ‘drawing room talks’ were organised on the theme of ‘Domestic Economy in Practice’ (reported in the Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 16th 1916). The venue was the Gymnasium, Ormond Road, Richmond and this second series of addresses by Mrs C. S. Peel, was aimed at domestic servants. The title, ‘How women can help to win the war’ reflected the preoccupation with the traditional view about women needing a recognisable role in the war that could be managed or even controlled. However, the aspirations of women themselves at that time to seize new opportunities highlighted the tensions and problematic contradictions that existed.

More tea, Mrs Peel?

The event itself was very sociable. Tea was given afterwards by Mrs Sandover and an enjoyable programme of music was provided by the Beechcroft Orchestra, followed by performances from Miss Wells and friends. This well-balanced programme indicated the strong desire of those ladies to ‘improve’ the servants that attended, providing them with an opportunity for entertainment and education that was not routinely available. The need to try to stay in control of the domestic labour force could also be considered a strong element motivating the ladies in charge of the arrangements.

Mrs Peel’s talk was described as ‘racy’ and covered 3 main points:

‘women could help to win the war… first by making munitions; second, by replacing men; and third, by saving the food, coal, and money of the country.’ (Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 16th 1916).

She described her audience as ‘home workers’:

‘… she wanted them to realise and bear in mind that their work was every bit as important and as essential to winning the war as that of the other two classes’. (Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 16th 1916).

She went on to emphasise:

‘What was even more important was that, owing to so many men having gone to fight, and so many ships having been sunk by the German submarines, there was now a national scarcity of food and coal, which had led to the great rise in prices. Unless the shortage could be made good in some way, the prospect before the country and especially the poorer classes, would be a very black one. English people were not naturally economical…’ (Richmond & Twickenham Times, December 16th 1916).

It would seem that everyone should do their bit to maintain stability and respect the existing social structures that appeared to underpin the efforts to practise war-time economy.

Schools breaking up for Christmas, 1916

In previous years the end of term for Christmas was the signal for ‘breaking up entertainments’ that were on a large scale. The shortages and the strife from the war created a damper on proceedings in 1916 according to a report ‘Breaking up for Christmas’, in the Richmond & Twickenham Times, 23rd December 1916. For example, the celebrations at Orleans Girls’ School were organised as a private occasion so neither the public nor friends were included. The programme included contrasting items such as a duet ‘Qui Vive’ performed by Alice George and Anna Eustratiades; ‘Wanted, a Governess’; ‘Santa Claus and the Mouse’ and ‘How Father made the Christmas Pudding’ (full details appear in the local newspaper). The whole affair was described as ‘a short concert’. Circumstances meant that a small-scale event was considered more practical.

Meanwhile, at Trafalgar Boys, the pupils and the teachers sent out a joint Christmas card which carried the message: ‘The teachers and scholars wish all the old boys who are fighting so bravely for their King and country as bright and happy a Christmastide as is possible, and good luck’. (the Richmond & Twickenham Times, 23rd December 1916). Their intention was to show all of the students now on active service that they were not forgotten and the list of those names took up 3 more sides included with the card. For the men who were ex-pupils involved in the forces it must have been a very poignant message, even bitter-sweet.

Trafalgar Girls (the Senior Class), invited a number of old girls and friends to an entertainment which took place on a Wednesday afternoon prior to the break for the Christmas holidays. The programme was varied, commencing with a carol ‘See amid the winter’s snow’ and as it progressed including a Japanese Fan Dance, other dances, piano music and a play. In presenting such a good programme in the face of the daily difficulties, the girls were striving to maintain a sense of normality and festivity. Such a creative endeavour was also a tremendous outlet for everyone involved, representing a release from the drudgery that had been imposed by un-relenting war time economy.

Love and loss

While emphasising the need to live life to the full (publicity in the local press encouraged couples to buy wedding rings to celebrate romance with a war-time wedding), tragedy (either direct or indirect) was difficult to avoid. The remembrance of Reggie, in the Surrey Volunteer Review is heart breaking in its simplicity and authentic sense of bereavement, love and loss.

Reggie’s death, described as ‘untimely’ was announced in the January 1917 edition of the Review. He had been a valued member of ‘C’ Company (the volunteers from Barnes). Known as Q. M. S. Wood, his close friends called him Reggie and considered him to be an excellent officer. He was a cheerful person and ‘… was just one of those kind, laughing and cheery souls the world at the moment can so ill spare.’ The circumstances of his death while in service are mentioned only as ‘swift and sudden’:

‘… nothing can efface the memory of the genial, good-hearted, splendid comrade who has “answered the roll-call” all too soon. Dear old chap, may the earth lie lightly on him’. (p 279 the Surrey Volunteer Review January 1917).

Reggie’s memorable image, the contented family man, brings home the tragedy of his loss at that time of year, emphasising the futility of war and its life-changing consequences for ordinary families. This was the ultimate constraint of the third Christmas of the war; how to endure such devastation was the question carried forward by many people into 1917.

Immerse yourself in the ‘Christmas 1916’ experience: visit Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library & Archive, the Old Town Hall, Whittaker Avenue, Richmond, TW9 1TP. Archive materials are varied and fascinating, providing a real insight into lives lived in the Borough at a crucial moment in history. They can be accessed with support from the Local Studies Team who are happy to share their expertise to help you successfully conclude your enquiries.

[Patricia Moloney, Heritage Assistant]