Utopia to Dystopia: Utopian ideas in Twentieth Century architecture

Utopia

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word Utopia as ‘An imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect’. ‘The opposite of Dystopia’. The word originates from the 16th century and is based on Greek ou ‘not’ + topos ‘place’; the word was first used in the book Utopia (1516) by Sir Thomas More.

Bournville

The Twentieth Century in particular saw an idealism in town planning and architecture, based on a Utopian model of living. From the altruistic visions for Port Sunlight and Bournville, the development of New Towns, to the housing schemes of post war Britain. Architects and planners were influenced by the idea of creating the perfect environment for ordinary people. Some of these schemes were successful, and remain so today. Others were not so successful and failed spectacularly, prompting the gradual demolition and re-development of many post-war housing estates. Some ideas such as Le Corbusier’s plan to re-build Paris, and Albert Speer’s futuristic vision for Berlin, assuming Germany would be triumphant in the Second World War, would never be realised.

Some of these ideas had their roots in Nineteenth Century philanthropy. In 1879 the Cadbury brothers moved their factory to a site four miles south of Birmingham and named it Bournville. They built a model village, incorporating schools, hospitals, public baths, parks and recreation, but due to there Quaker beliefs there were no pubs! The houses they built were light and airy and had large gardens. The mental and physical health of their workers were central to these plans and they didn’t see why their workers should have to live in squalor.

Similarly, Port Sunlight was built between 1899 and 1914 by the Lever Brothers to house the workers from their soap factory in the Metropolitan Borough of the Wirral, Merseyside. They were influenced by the writings of William Morris and the Arts and Craft Movement and wanted to create decent conditions for their workers, while also encouraging them to engage in art, science, literature and music.

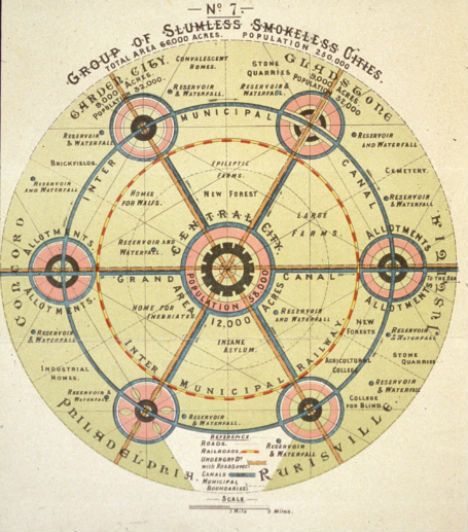

In 1902 Ebenezer Howard wrote Garden Cities of Tomorrow, which aimed to deal with the overcrowding, filth and disease of urban living, re-thinking how people lived, and give the working classes a better quality of life, to include access to park land and eradicating slums. He included the development of suburbs and areas of open space.

Ebenezer Howard’s blueprint for slumless cities.

These ideas would form the basis for many of our suburbs and in particular the Garden Cities. The Garden City Movement was formed as a direct result of Ebenezer Howard’s book and 1903 saw the development of Letchworth as the first Garden City, followed by Welwyn Garden City, built in 1920.

Garden Cities of Tomorrow by Ebenezer Howard (Faber and Faber 1960). New Towns. Their Origins, Achievements and Progress by Frederic J. Osborn and Arnold Whittick (Leonard Hill 1977). Transport Planning in the Garden Cities by Stephen Potter (Open University 1981). All available from Twickenham Library Store.

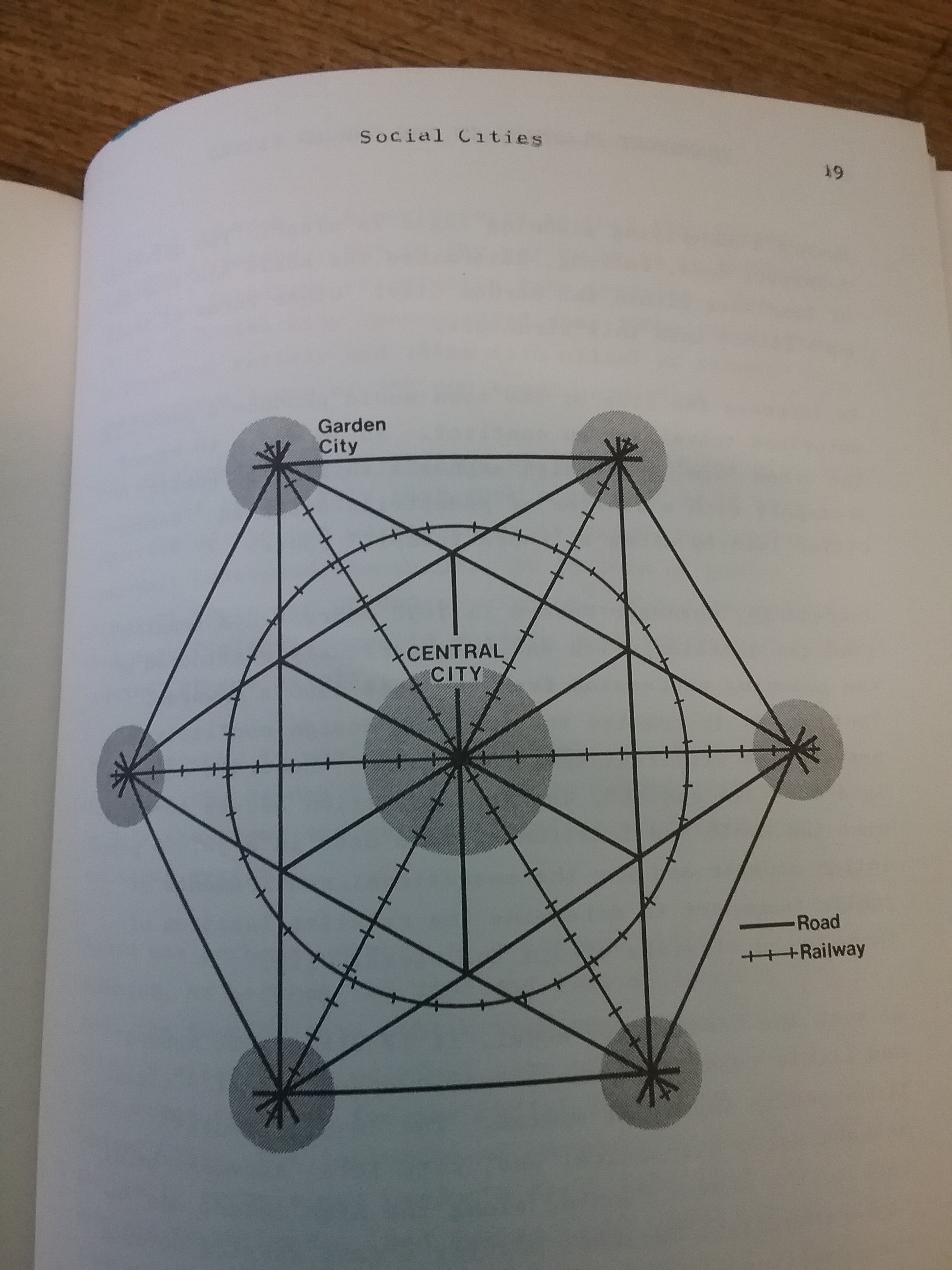

From Transport Planning in the Garden Cities by Stephen Potter (Open University 1981).

Ebenezer Howard envisaged a Social City, a cluster of garden cities surrounding a central city, all linked by a rapid transport system.

Subtopia

London Suburbs. Introduction by Andrew Saint (Merrell Holberton 1999)

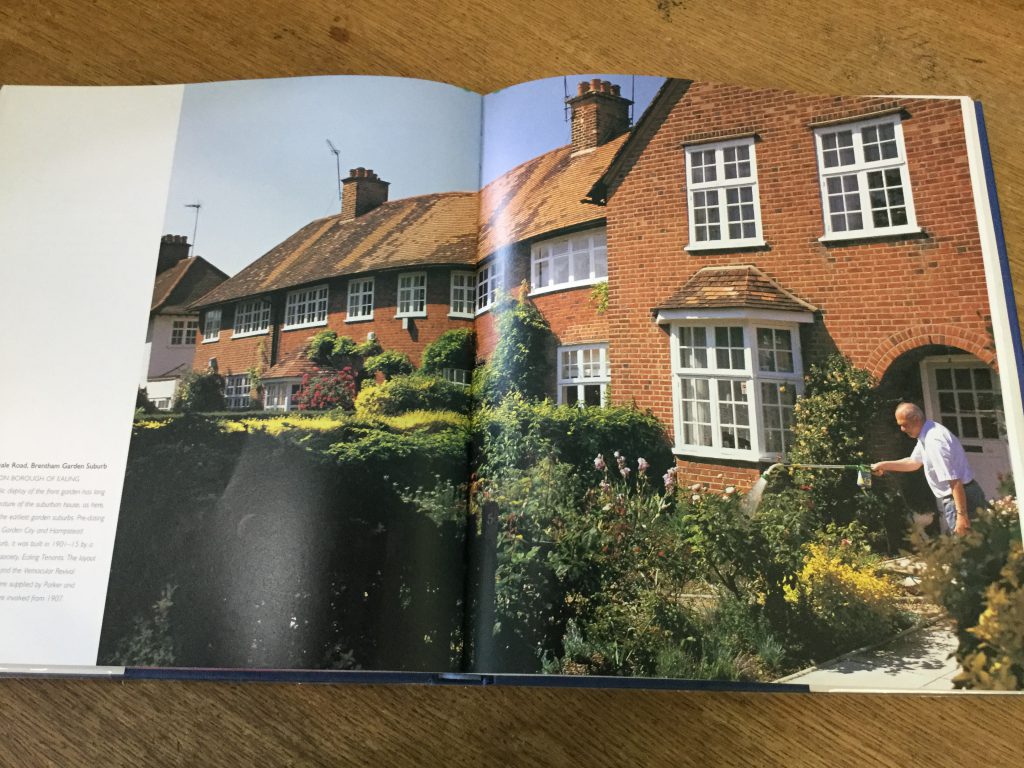

The most visible and enduring legacy of Howard’s ideas can still be seen in London’s suburbs. One of the earliest garden suburbs was Brentham Garden Suburb in the London Borough of Ealing, built between 1901 and 1915. It pre-dates the more famous Hampstead Garden Suburb and was the first Garden Suburb in London to be built on co-operative principles, the design based on both the Arts and Crafts and the Garden City Movements.

Meadvale Road, Brentham Garden Suburb, London Borough of Ealing. From London Suburbs. Introduction by Andrew Saint (Merrell Holberton 1999)

After the Second World War there was a massive housing shortage in London and the South East. Coupled with a slum clearance programme and a growing population, it became clear that a substantial building programme was needed and this fueled a boom in housing and expanding transport systems. Some of these developments proved more successful than others.

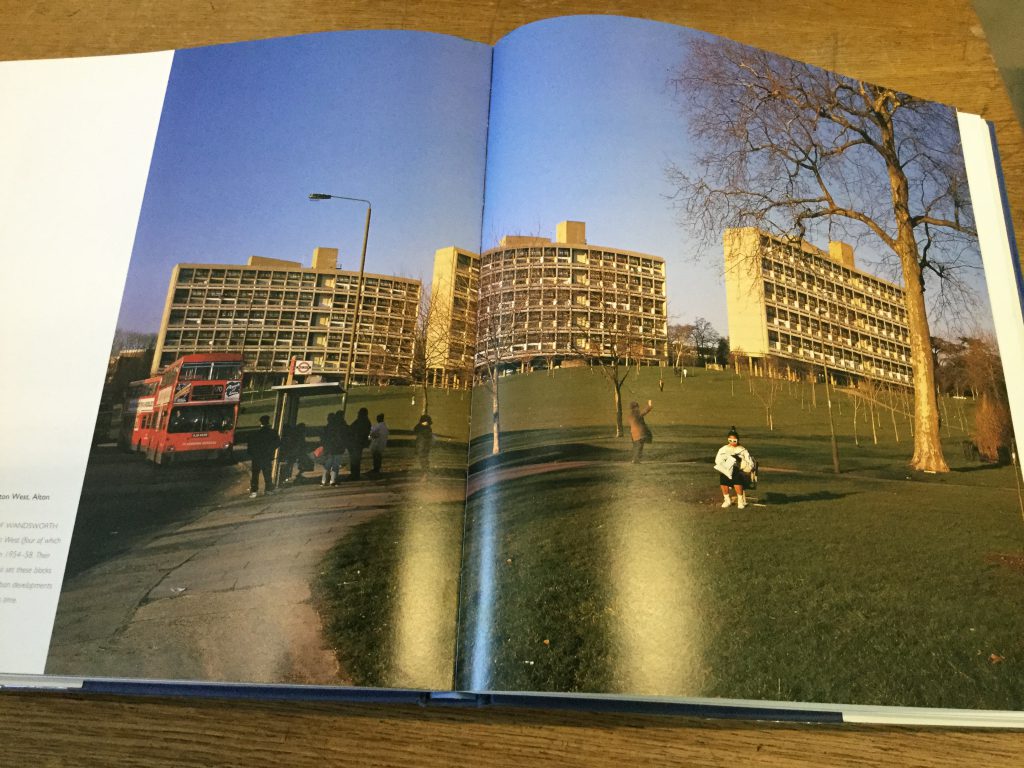

Alton East and Alton West in Roehampton, bordering Richmond Park, was a low and high rise social housing estate built by the London County Council in 1959. Set within a large open area it is built using a slab concrete construction and is based on the work of modernist architect Le Corbusier It is considered a good example of this type of housing development, due to the mixed density of housing and extensive green space. Much of the development is now listed and acknowledged as architecturally significant.

From London Suburbs. Introduction by Andrew Saint (Merrell Holberton 1999)

Dystopia

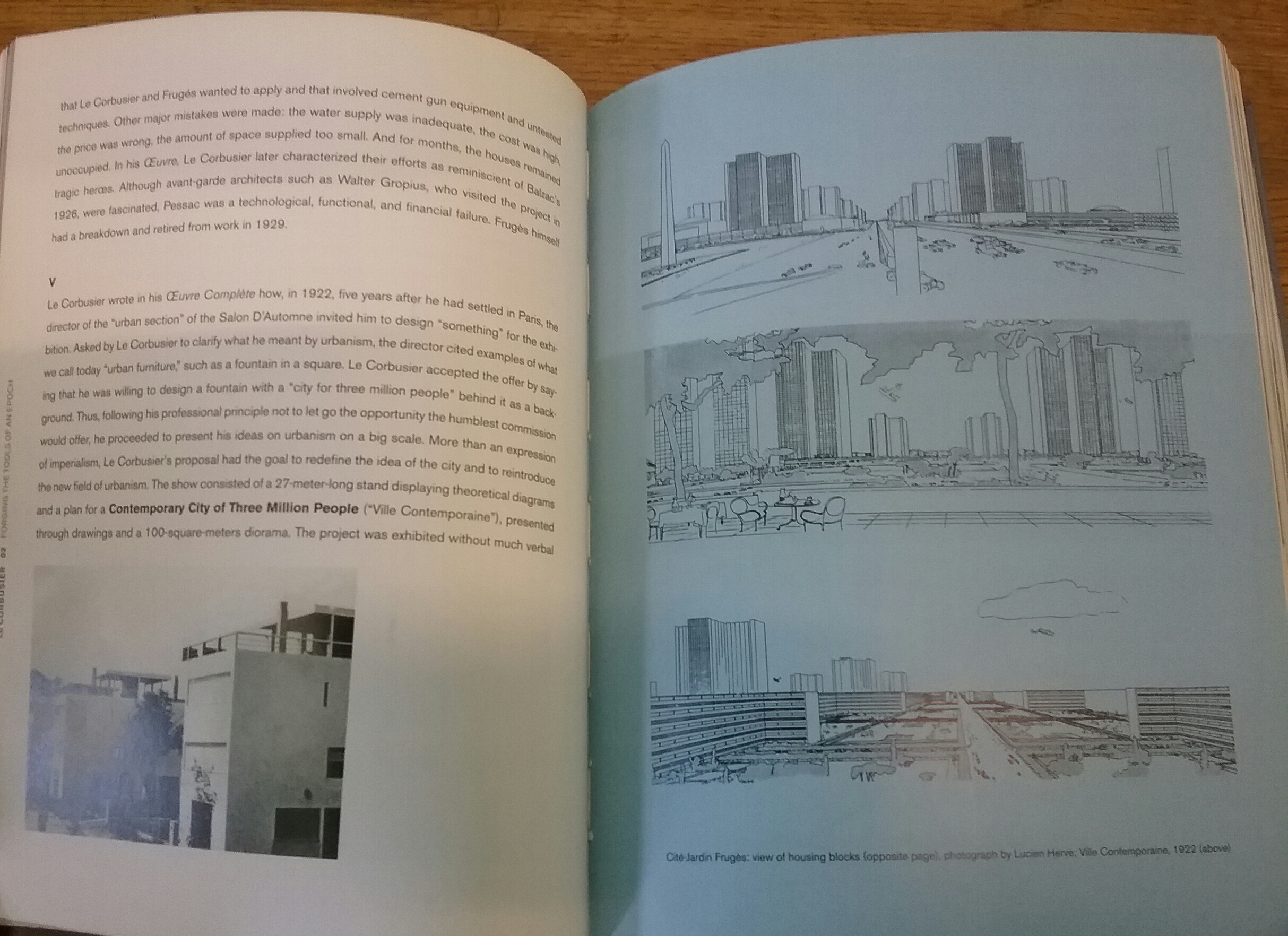

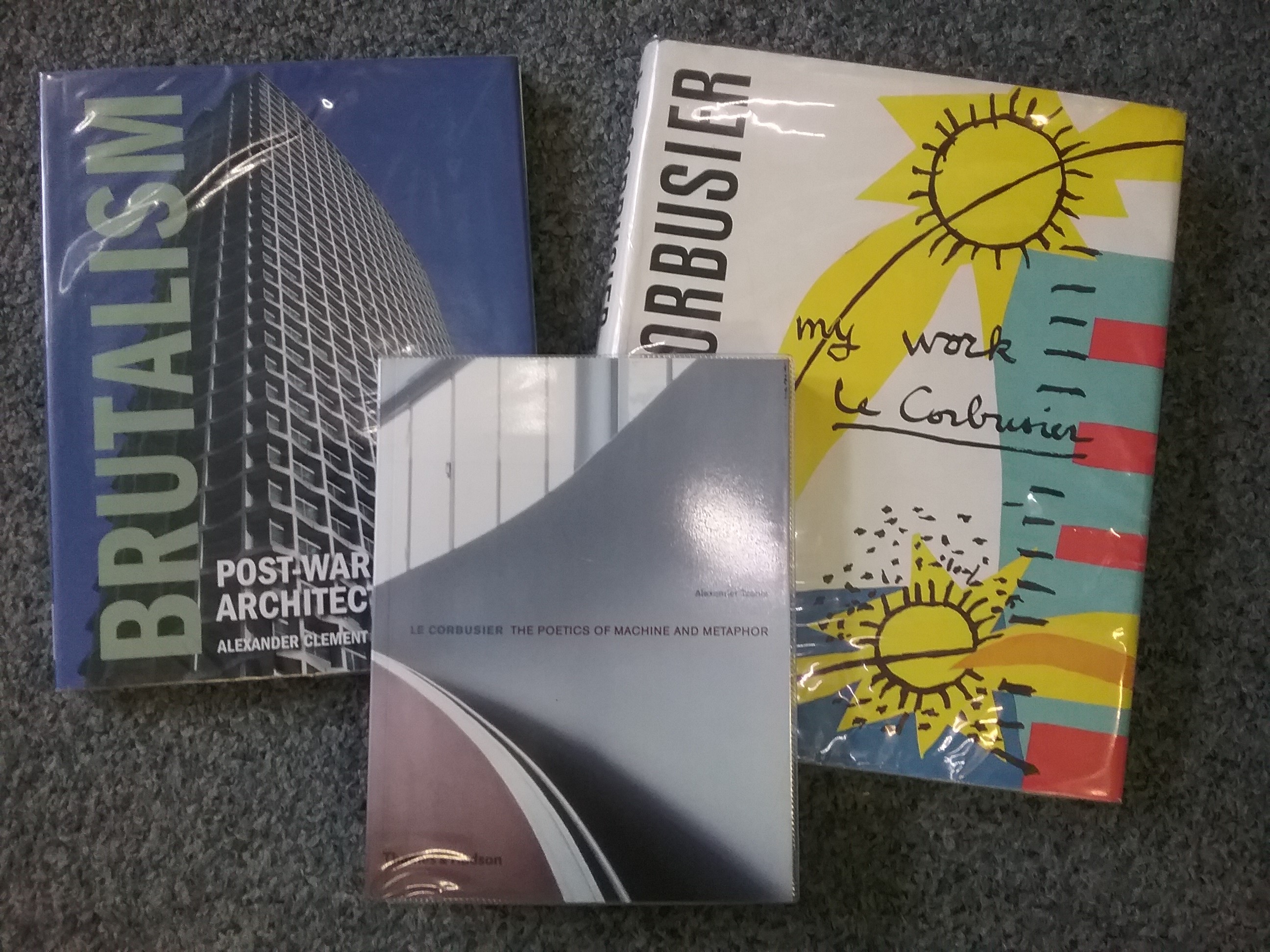

Le Corbusier’s blueprint for a Contemporary City of Three Million. From Le Corbusier. The Poetics of Machine and Metaphor by Alexander Tzonis, Thames and Hudson 2001.

Despite these successes, some projects were to become infamous rather than famous. Architects took the principles of Le Corbusier and his idea of ‘cities in the sky’ in order to create cheap and plentiful social housing, without taking into account the damp climate and the social problems associated with slum clearance. Thamesmead is a prime example. Built in the London Boroughs of Greenwich and Bexley in the late 1960’s it came to epitomise the failure of post-war planning. It was used as the the backdrop for the film A Clockwork Orange, based on the Dystopian novel by Anthony Burgess. Thamesmead was based on Modernist ideas, using concrete construction. However, concrete proved to be an unsuitable material in the damp English climate and estates of this nature were dogged with problems. The estate was cut off from major transport links and it lacked basic facilities such as shops. Social engineering based on modernist ideology failed. Walkways and communal spaces were meant to encourage a sense of community and replicate the slums they had replaced but instead it led to anti-social behaviour. Corbusier’s ideas were based on homes for professionals in the city, and were not suitable for the young families now housed in high rise blocks and isolated from from the communities they knew. This idea was replicated across London and many major cities. Many of these developments have now been re-developed or demolished, and replaced with more traditional housing and sustainable housing.

Some ambitious Utopian schemes never came to fruition, such as Albert Speer‘s plans to demolish Berlin and rebuild it in the event of Germany winning the War, and Le Corbusier’s ambitious vision during the 1920’s to demolish the the Right Bank of the River Seine in Paris. He was heavily influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s book and the Garden City Movement. At the time, this area had become run down and squalid. Le Corbusier’s vision was to build 18 cruciform glass towers with triple-teared pedestrian malls and terraces and set in a huge park. There would be train and subways systems and an airport as well as a business centre but a small number of buildings of architectural merit would be preserved.

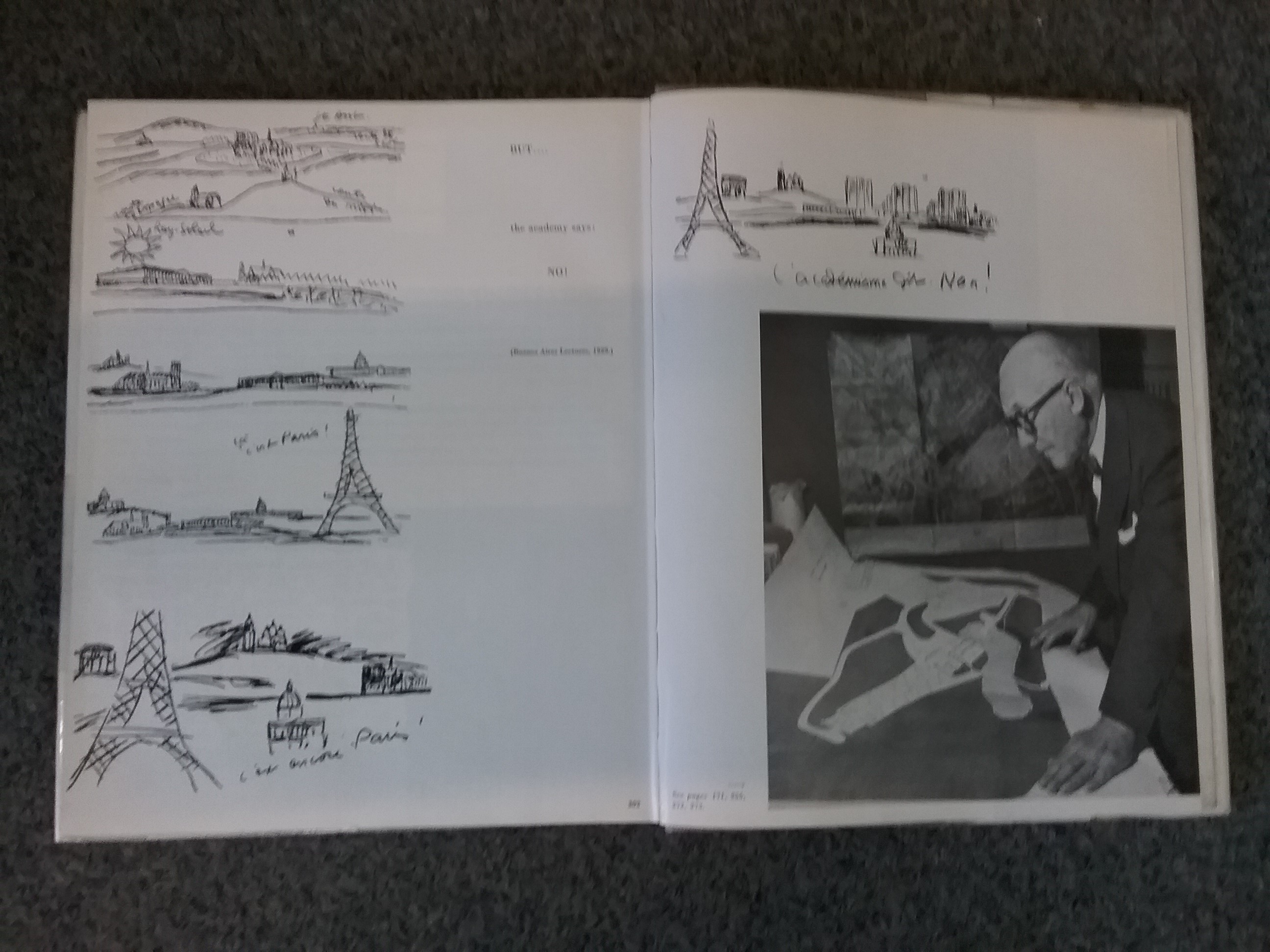

Le Corbusier’s sketches of Paris. From My Work Le Corbusier, Architectural Press 1960

Unless otherwise stated, all the books credited are available at The Information and Reference Library alongside an extensive and varied collection of titles covering architecture and design.

[Gina Morley, Library Assistant]