Follow the Drum: Changing roles on the Home Front

The Mabys Association.

The Mabys Association.

At the outbreak of war the role of women was very restricted in all levels of society, particularly for working women such as servants.

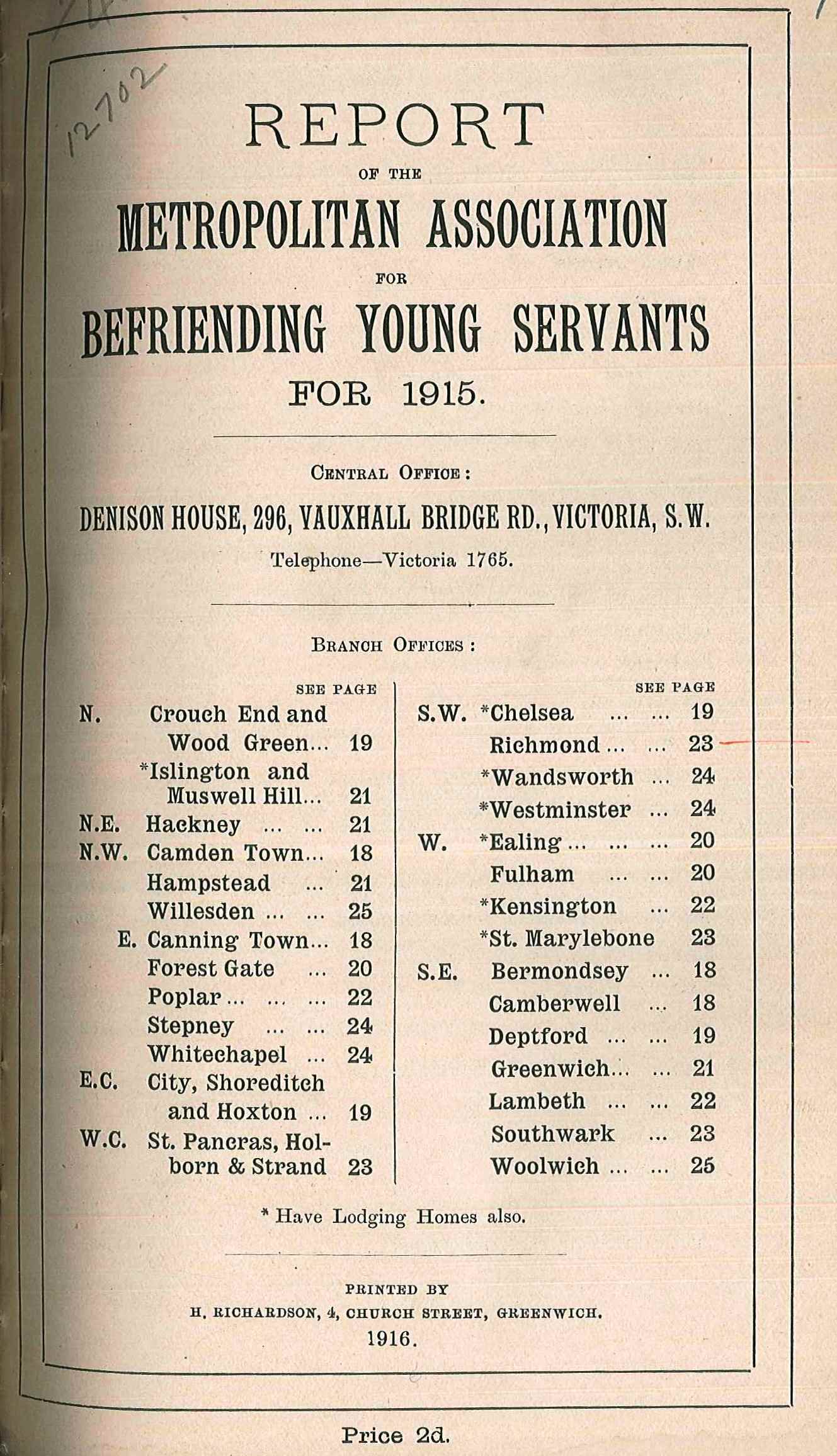

The Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants or Mabys (established in 1874 to “befriend young women working in service and ensure they performed their duties as servants correctly, avoiding poor conduct”) strove to retain women in service and developed a system of certificates for achieving excellence. The certificates, four hundred and fifty-five of which were awarded in 1916 alone, were accompanied by a copy of a personal letter from HRH Princess Christian assuring the women that they were doing ‘their bit’ for the war effort.

Between 1913 and 1914 the local branch of the Mabys for Richmond and Kew was having difficulties retaining the numbers of women actively participating in their meetings. In 1915 they turned their office on Richmond Green into a certified training facility called The Princess Mary Adelaide Training Home, but this was to close shortly afterwards as the number of domestic workers diminished due to many women abandoning domestic service to take up employment opportunities elsewhere. The Mabys redirected their energies into seeking helpers that had experience in social work and business due to the war, viewing their renewed efforts as part of the reconstruction efforts.

Find out more about the work of the Mabys by reading the volume of reports held in the Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library & Archive.

A Domestic prosecuted for theft.

A case that came before the Mayor (Councillor T. Terry) and other local magistrates at Richmond Police Court in April 1915 illustrates the social turmoil of this time. Domestic servant Daisy Soley, aged 24 was accused of stealing a gold bracelet and gold brooch from her employer, Mrs Ethel Jenkins of Burlington Avenue, Kew (Richmond & Twickenham Times 17 April 1915, p 7). Jenkins told the police that she did not want to prosecute as Soley admitted the theft of the brooch and blamed it on her family’s impoverished situation – more detailed enquiries into her background revealed that the death of both her parents had left Daisy to provide for her younger brother and two younger sisters on her own.

Soley had attempted to pawn the jewellery, claiming that “her young man had given it to her before he went to the war” and using her sister to corroborate this story, but the pawnbroker went to the police. The Magistrates bound her over to probation for six months and a fine of £5, ordering the return of the stolen items to Mrs Jenkins.

Women in the workplace, 1915

With the traditional bread-winners away at the front, women were increasingly in a position of having to fill places in the workforce to maintain its strength. This represented an immense social change and long-established behaviours would be challenged as the pressure for change mounted against the back-drop of this hugely destructive war. At the forefront of this drive for social change was the issue of women’s suffrage.

There were a range of reasons why women were motivated to take a more prominent role at work, such as the chance to gain new experiences and skills, and the attractive prospect of financial remuneration (albeit not equivalent to a man’s wage). In at least one local case it was a way to maintain a family business as long as the conflict progressed, as presented in the Richmond & Twickenham Times (12 June 1915). The story entitled ‘The First Milkwoman in Richmond’ concerned Mrs Humphrey, who had to undertake the milk-rounds in order to save her husband’s business. Due to the employees of this milk business enlisting (one in the navy and the other in the army) she was left in the position of single-handedly sustaining the family business. Her initiative is portrayed as a patriotic act but it indicates how the lack of man-power was impacting on the local working population, the newspaper proclaiming that “by undertaking the delivery of the milk Mrs Humphrey has pluckily saved the situation”.

A photograph of Mrs Humphrey as she strived to make a living and retain the customer base for the family business on her own accompanies the article, available to view on microfilm in the search room of the Local Studies Library and Archive.

Women were not only moving away from their traditional roles in the home but also from positions such as domestic service into industrial settings: production of munitions and manufacturing of aircraft are two examples and these activities that could be found locally during this period.

Women police officers: the necessity for their work.

During the spring and summer of 1915 the local newspapers were also reporting the debate about the need for women police officers. In May 1915, Alderman J. J. Bisgood sought to remind people about the existence of the Pankhursts’ Suffragette movement and the effects of the pre-war struggle for women’s rights in an article published in the Richmond & Twickenham Times (8 May 1915, pp 5-6).

Responding to leaflets and a meeting held in April 1915 supporting the introduction of women police officers, he described the Woman’s Social and Political Union as being in a “hibernating stage” whose political objectives were criminal and had detrimental effects both locally on the young female population and also abroad, claiming that the Germans had formulated an opinion about Britain as a result of the women’s direct action and violent protests:

“Young women of hysterical temperament… were suborned to commit these outrages… all evidence points to the fact that the Germans, in formulating their ideas of British decadence, laid great stress on the hopeless weakness of a country which was unable, through lack of firmness of character, to suppress the criminality of a few hundred dangerous females.”

Bisgood strongly believed that the movement was aiming “by a policy of ‘frightfulness’ […] to terrify the Government and the people of this country into setting the reform that they desired in front of all other reforms.”

Nonetheless, a march in support of women police officers, from Richmond railway station to the Castle Assembly rooms (Whittaker Avenue) was reported in the Richmond & Twickenham Times of 24 April 1915 (p 6). The march, which took place on 23 April 1915, was held under the auspices of Richmond Women’s Suffrage and the following meeting was attended by the Mayor (Councillor T. Terry), his mace-bearer (Mr Coker), Lady Nott-Bower, Lady Yoxall and the Rev. Max Binney among others. Spontaneous bursts of applause from those attending are noted throughout and the meeting was conducted positively despite the ‘controversial’ topic under consideration. Finally, though funding for two women police officers was needed the Mayor was persuaded to ‘think the matter over’.

[ by Patricia Moloney, Heritage Assistant ]