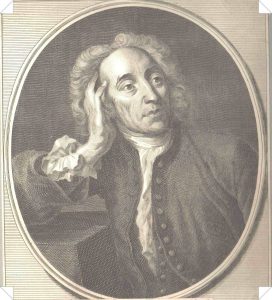

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) – [Local History Notes: 16]

Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets records a statement, attributed to Lady Bolingbroke, to the effect that Pope could ‘hardly drink tea without a stratagem’. Pope’s career was, indeed, an almost relentless story of intrigues, quarrels and deceptions conducted against his enemies in the literary world and leading society of his age.

He was born in Lombard Street, London on 21st May 1688, the son of a linen draper. By 1700, his family had moved to Binfield in Windsor Forest. A precocious child, he began to study Latin and Greek at the age of eight. When he was twelve, he developed a severe illness as a result of which his constitution was greatly weakened and his figure permanently deformed – he never, apparently, grew above the height of 4 feet 6 inches. After attending schools in Twyford (near Winchester) and London, he returned to his father’s house where most of his time was spent in reading or writing.

He managed to become acquainted with the influential wits of his time, including Sir William Turnbull, William Walsh the critic and William Wycherley the dramatist.

In 1709 his Pastorals were published in the sixth part of Tonson’s Poetical Miscellanies. The Essay on Criticism, a characteristically epigrammatical work, was published anonymously in 1711. In the following year the Rape of the Lock appeared in its first form in the Miscellanies published by Lintot. The work was subsequently revised and enlarged and published in 1714. It was inspired by a contemporary incident in which the young Lord Petre had cut off a lock of the hair of Arabella Fermor, a noted beauty.

Pope’s membership of the Scriblerus Club – an informal association which included Gay, Parnell, Swift, John Arbuthnot, Congreve and Francis Atterbury – helped to strengthen his position as a leading man of letters.

Encouraged by Trumbull and others he launched into a translation of Homer’s Iliad. The first volume was published in June 1715, at about the same time as a translation of the same work by Thomas Tickell. Pope’s jealously was aroused: he was convinced that Addison (an associate of Tickell) was the real author. The final volume of Pope’s translation appeared in May 1720.

In 1719, he bought the lease of a house in Twickenham, with five acres of land. Here he lived for the rest of his life, enlarging the villa – the architect was James Gibb who also designed the Octagon at Orleans House – and taking great pleasure in laying out the grounds. For the latter he had the assistance of the professional gardeners William Kent and Charles Bridgeman and his friends, the Lords Peterborough and Bathurst. The celebrated grotto was, in fact, an imaginative method of linking the riverside gardens with the gardens which lay on the other side of the road leading from Twickenham to Teddington. The grotto was ornamented with spars and marble, many of them sent from Cornwall. The gardens included an obelisk to the memory of the poet’s mother (who died in 1732 and was buried in Twickenham Parish Church) and also the second Weeping Willow planted in England.

At about the time he came to Twickenham he became acquainted with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (who lived in Twickenham for a period) and with the sisters Teresa and Martha Blount. His friendship with Lady Mary was ended abruptly by a bitter quarrel – after which she became his arch-enemy. The relationship with the Blount sisters was more enduring, although it cooled considerably when Pope suspected that Teresa was guilty of spreading rumours questioning the innocence of his affection for Martha.

In May 1728, The Dunciad appeared anonymously, a note from the publishers implying that it had been written by a friend of Pope. In this work the poet attacked all his foes, whose names were represented by initials only. In March of the following year an enlarged edition appeared, with the names spelt out in full. The identity of the author, however, was not acknowledged until The Dunciad appeared in the 1735 edition of Pope’s Works.

The four Moral Essays were published between 1731 and 1735. The first book of the Essay on Man came out in 1733 with the remainder following within a year. The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot (1734-5) – a retaliation to a joint attack in writing from Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Lord Hervey – and his Letters, published shortly afterwards, are valuable both for their high literary merit and as autobiographical documents.

A reference to the actor and dramatist Colley Cibber in the New Dunciad (1742) occasioned the last literary quarrel of Pope’s life. By this time his health was rapidly declining. He died on 30 May 1744 and was buried on 5 June at Twickenham Parish Church, by the side of his mother. He had directed that the words ‘et sibi’ should be added to the inscription on his parents’ monument on the east wall of the Church. In 1761, his friend William Warburton erected a monument on the north wall with the inscription ‘to one who would not be buried in Westminster Abbey’.

After Pope’s death the villa was sold to Sir William Stanhope (Lord Chesterfield’s brother), who enlarged the house and gardens. On his death, the property passed to his son-in-law, the Right Hon. Welbore Ellis. In 1807 the property came into the possession of Baroness Howe who, in the words of R.S. Cobbett ‘razed the house to the ground and blotted out utterly every memorial of the poet.’ She built a new house, about a hundred yards from the site of the original villa – all that survives of Pope’s villa is the Grotto now under the buildings of the school. A later owner, Thomas Young, built yet another house near the site. This was a somewhat fanciful building with a ‘Chinese Gothic’ tower and it now forms part of the buildings of St. James’s Independent School in Cross Deep.

The famous Weeping Willow in Pope’s garden died in 1801 and the remains were made into relics.

In 1888 the bicentenary of Pope’s birth was marked in Twickenham by an exhibition of portraits and other items associated with the poet.

Suggestions for further reading

Many books and articles have been written on Pope’s life and work. The following is a brief list of some sources for further study:

Batey, Mavis / Alexander Pope: the poet and the landscape. 1999

Cobbett, R.S. / Memorials of Twickenham. 1872

Dictionary of National Biography article on Alexander Pope

Ironside, Edward / The history and antiquities of Twickenham. 1797

Jack, Ian / Pope. 1962 (Writers and their work, No. 48)

McDonald, W.L. / Pope and his critics. 1951

Martin, Peter / Pursuing innocent pleasures: the gardening world of Alexander Pope. 1984

Montagu, Lady Mary / The complete letters… 3 volumes; edited by Robert Wortley Halsband. 1965-1967

Paston, George / Mr. Pope: his life and times. 2 volumes. 1909

Pope, Alexander / The correspondence…5 volumes; edited by George Sherburn. 1956

Quennell, Peter / Alexander Pope: the education of genius 1688-1728. 1968

Simpson, Donald / Twickenham past: a visual history of Twickenham and Whitton. 1993

Sitwell, Edith / Alexander Pope.

More information on other people and places of interest in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames is available from the Local Studies Library & Archive.