London: the city as a phoenix [Part 1] – The Great Fire of London

On the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London we take a look at how London has risen, phoenix-like, from conflagrations, both man-made and natural, after the Great Fire and after the Second World War.

The Great Fire of London

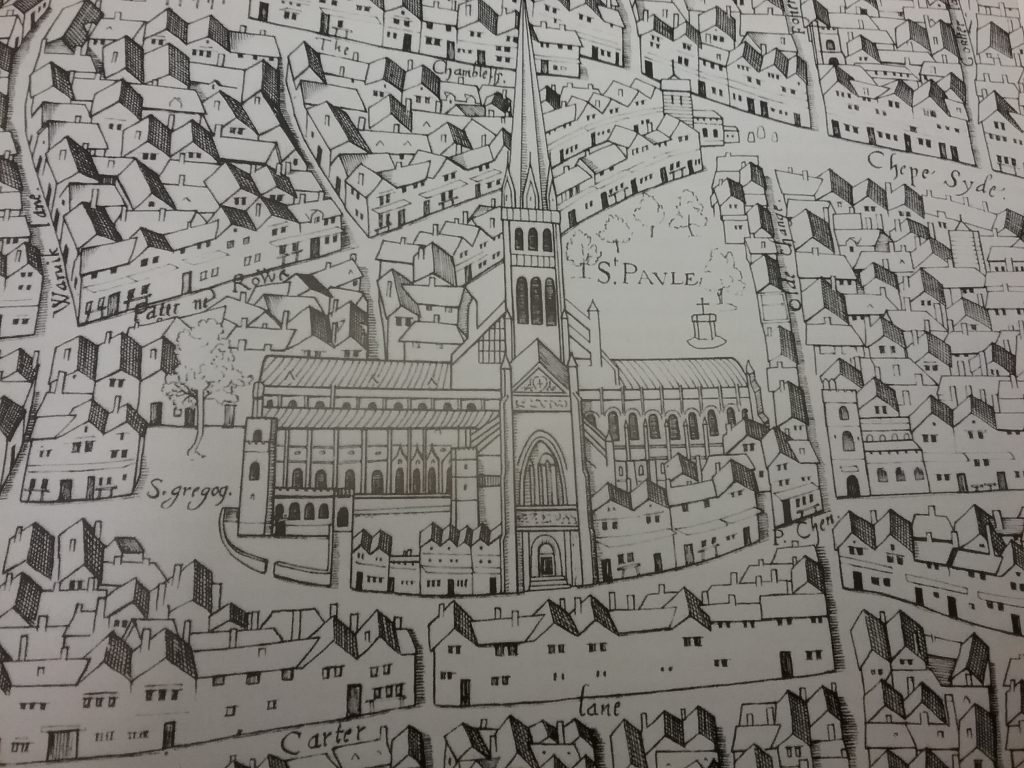

The earliest destruction of the City of London was in AD61 when Boudon, and her tribesmen, destroyed and burnt the early Roman London settlement on the banks of the Thames. Fires were not an unusual occurrence in a time when buildings were mainly built of combustible materials such as wood and thatch and when open fires and naked flames were used for heating, cooking and lighting. The City of London’s narrow, twisting streets and lanes, and the tightly packed buildings, meant that the City was particularly susceptible to fires (see 4 below). No planning laws or building regulations existed then though, late in the C12th, a rule was introduced that the lower parts of houses in the City should be built of stone and the roofs tiled – but this wasn’t implemented. As an anti-fire measure each ward in the City had to have implements (such as poles, hooks, and chains) that would aid in the demolition of a burning building; the idea being that this would halt the spread of fire from one property to another.

The Great Fire of London acquired the name because it lasted for so many days – from 2nd September to 5th September – and was so destructive. The fire began at 2am on Sunday 2nd September 1666 when a workman in Thomas Farriner, King Charles II’s baker’s house* on Pudding Lane smelt smoke and woke the household. The baker, his wife and child escaped over the rooftops (which is itself an indication of how tightly packed were the buildings) but their maid, who was too scared to follow, burnt to death.

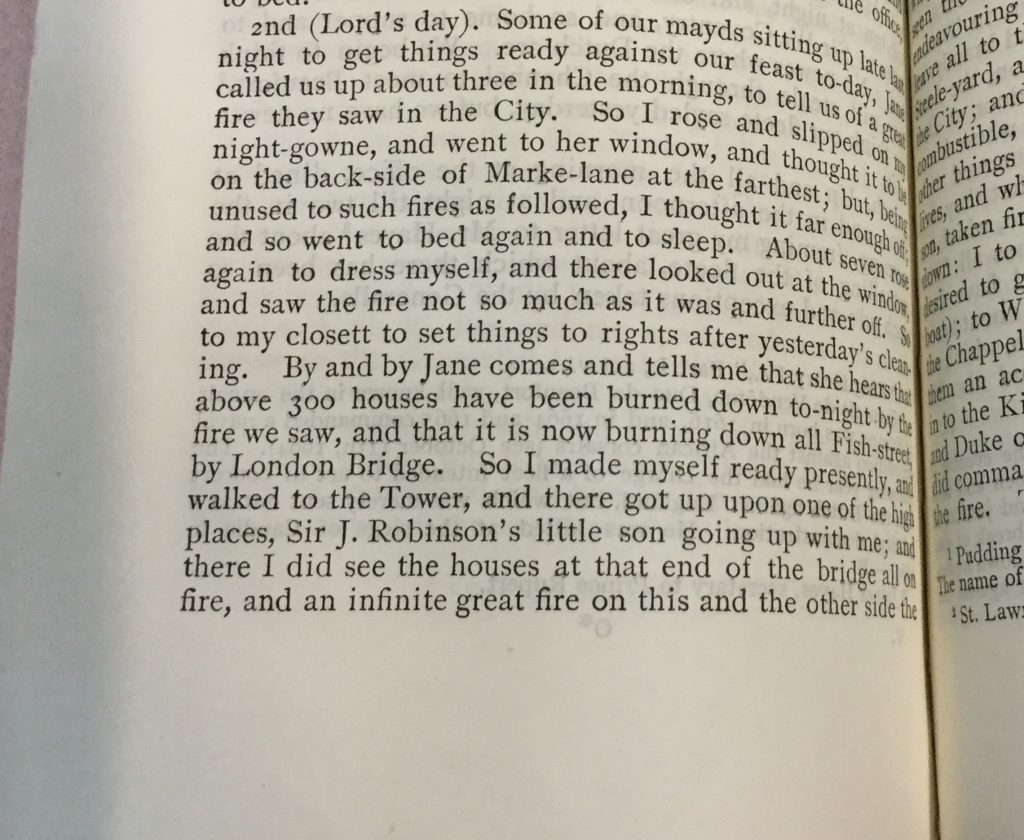

We have a vivid, emotive eyewitness account of the fire by the candid, observant Samuel Pepys who described the chaos and destruction that the fire caused. In his diary entry for 2nd September 1666 (Lord’s Day) Pepys said:

Some of our mayds sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast to-day, June called us up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose and slipped on my night-gowne, and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back-side of Marke-lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off; and so went to bed to again and to sleep.

Pepys took a boat on the River Thames and observed how people flung their goods into the river or into lighters (small, flat-bottomed barges used to transport goods and people between ships and to the shore) and he even noted the plight of the pigeons:

And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down.

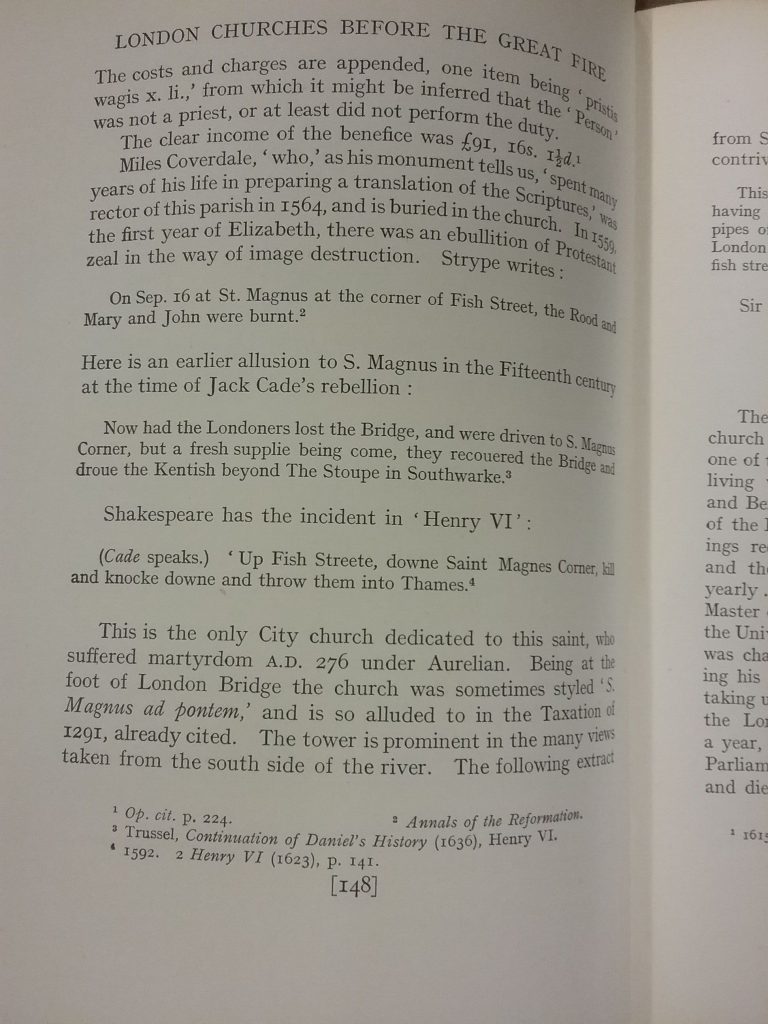

Even then pigeons were the quintessential birds of London, 160 years before Trafalgar Square was laid out. He talks about the high wind that drove the fire westwards to the heart of the City and the drought that made everything tinder dry so that “every thing… providing combustible, even the very stones of churches”. He mentions that St Magnus the Martyr was burnt. (see 3 below).

Pepys describes how the King (Charles II) gave orders for houses to be pulled down to prevent the spreading of the fire but this was to no avail and the conflagration continued.

By the evening of the 2nd the fire was threatening Pepys House on Seething Lane, which was just over a quarter of a mile from where the fire started in Pudding Lane. The Pepys moved there in 1660. The lane still exists today and Pepys Street is one of the streets off of it.

On Tuesday 4th September the fire was still raging and Pepys, along with other Londoners , was trying to save his possessions and he put his Parmazan (sic) cheese and his wine and also some papers in a hole in the garden for safekeeping. Pepys reports how the Navy used gunpowder to blow up buildings next to the Tower to stop the progress of the fire and by Wednesday the 5th the wind had dropped and the final fires were extinguished. Pepys walked around the City and reported on the devastation that he saw, including that to St. Paul’s whose roof had been burnt and had fallen in. He climbed to the top of All Hallows by the Tower to survey the nearly 400 acres that had been burnt in the City.

Had Pepys been alive in the C21st he might have been blogging and tweeting about the fire and putting photos on Instagram!

Luckily, there was little loss of life with only nine victims but the activities of of the City had been curtailed and 13,200 houses, 44 livery halls, 87 churches, the City gates, the Guildhall, St.Paul’s Cathedral and the Royal Exchange had been either partially or wholly destroyed. The homeless Londoners camped out in tents and makeshift shelters in the fields beyond the City.

St. Paul’s Cathedral and the rebuilding of the City

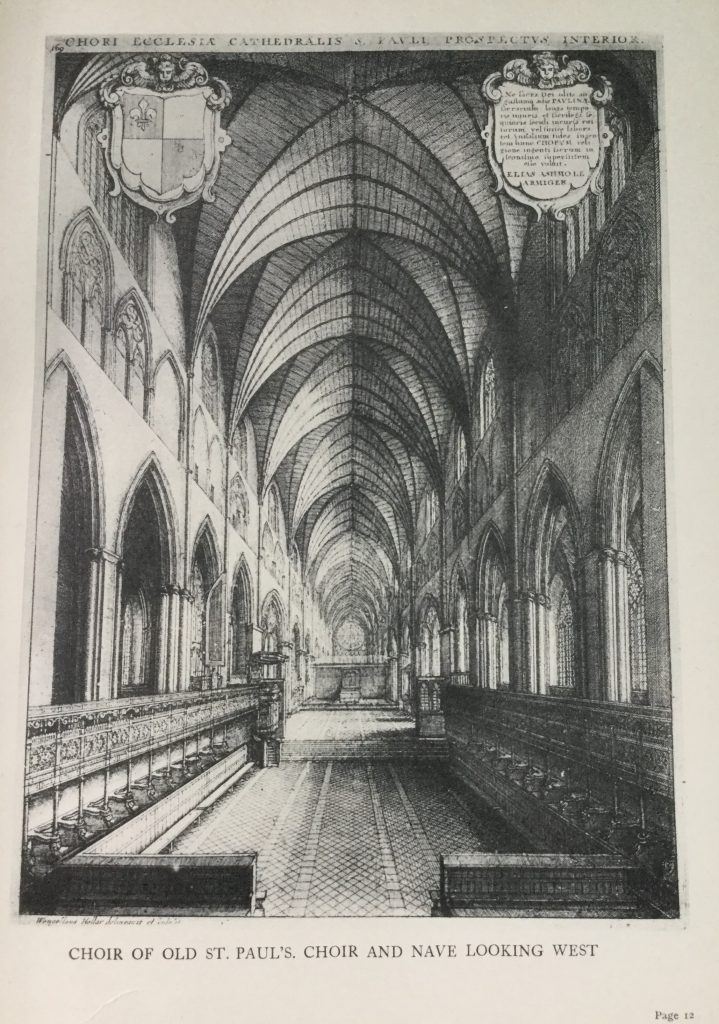

According to Bede, the first St. Paul’s was founded in 604. It was subsequently destroyed by fire in 962 and 1087 and was then rebuilt as a magnificent Norman stone cathedral, one of the largest at the time, with the tallest spire that had ever been built. The Cathedral had been badly neglected and when the spire was struck by lightning in 1561 it was not rebuilt.

3. St Paul’s as depicted in the ‘copperplate map’ of London of the 1550s. The first known view of the cathedral before the spire was struck by lightning and fell in 1561. It also shows how closely packed the buildings were in the City.

In the early C17th funds had been raised to restore and repair the badly neglected cathedral and Inigo Jones, was appointed as honorary architect for the project and work began in 1633 but it was interrupted by the Civil War. In 1663 Sir Christopher Wren recommended to the Dean and Chapter that the unstable Medieval crossing tower be taken down and replaced with a classical dome. His design was inspired by the church architecture of Paris, which he had recently visited.

However, the Great Fire put an end to the project when the old St Paul’s was reduced to ruins. Wren was eventually commissioned to build a new cathedral in its place and to rebuild many of the City’s parish churches. The rebuilding was completed in 1710 and and once again the City skyline was dominated by St. Paul’s. It would continue to do so until Wren’s dome was overshadowed by the skyscrapers that were built in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

The rebuilding Of the City and the construction of the Monument

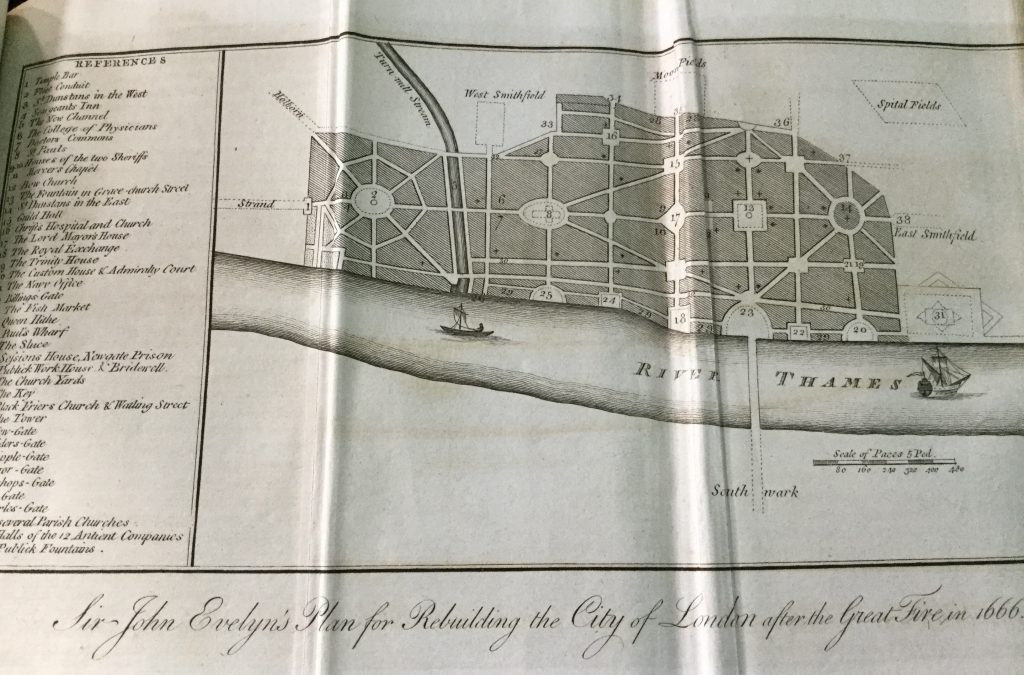

John Evelyn and Wren both put forward proposals for rebuilding and redesigning the City (see above). They both envisaged an Italianate city with piazzas and wide streets. These were rejected as being impractical and, as a result, parts of the street pattern that we see today are Medieval or even Roman. The rebuilding process was slow and took around ten years, with progress being impeded by property disputes. The Guildhall was completed in 1669 and by 1672 most of the houses were completed. There were now restrictions on the number of storeys that buildings could have.

The Monument, as it was to become known, was designed by Wren and Dr Robert Hooke and was erected between 1671 and 1677 to commemorate the fire and the rebuilding of the City. It is a Doric column, of Portland stone, with a viewing platform reached by a cantilevered stone staircase of 311 steps. This is surmounted by a drum and a copper urn from which flames emerged, symbolising the Great Fire. The Monument is 61 metres high (202 feet) – the exact distance between it and the site in Pudding Lane where the fire began. It was the tallest structure when it was built and was only superseded when the dome of St. Paul’s was erected. The Shard – currently the tallest building in London – can be seen from the Monument.

In Part Two we will look at how the fires and destruction caused by the Blitz during the winter of 1940-41, and later on in the War, caused some of the most serious damage to the City since the Great Fire.

[*Pepys refers to the “King’s baker’s house” and it isn’t clear if this is the house where the baker, Thomas Farryner lived, or whether it was where the bakery was too.]

Related links and source material

Map of the Great Fire of London

The Monument

Museum of London

Pepys’ complete diaries are available online at Pepys diary

RIBA’s Drawing Collection

Bibliography

The Architecture of Wren

The Diary of Samuel Pepys

History and Description of London, Westminster and Southwark,

London: The Biography

London Churches before the Great Fire

London Encyclopedia

London : A History

St. Paul’s: The Cathedral Church of London 604-2004

Image sources

1.The Diary of Samuel Pepys M.A., F.R.S. page 392

2. St. Paul’s: the Cathedral Church of London 604-2004, page 55

3. St. Paul’s: the Cathedral Church of London 604-2004, page 45

4. London Churches Before the Great Fire, plate 11, page 12.

5. A History and Description of London, Westminster and Southwark, Volume 1, page 246

Library members can access the entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Oxford Art Online for the people listed above by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text.

[Fiona Campbell, Library Assistant]